IB Physics Topic 2 Notes

B1: Thermal energy transfers

Phases of matter

In Topic A.3, considerable time was taken in expanding on the types of energy you will encounter during IB physics. However, when considering the behavior of energy and how it transfers between objects, you need to understand how the particles within objects behave to store and release energy.

To begin, remember that each object can present itself as a state of matter (solid, liquid or gas) but can switch between them. The kinetic theory governs the properties of each phase: solids, liquids, and gases.

- Solids have a fixed volume and shape because their particles vibrates around a fixed position held there by strong intermolecular forces. This is typically the densest phase.

- Liquids have a fixed volume and fill the shape of their container, because their particles slide over one another due to weaker intermolecular force. This phase typically has an intermediate density.

- Gases do not have a fixed volume and fill the shape of thier container, because their particles move randomly in space due to their very weak intermolecular forces. This phase typically has the lowest density.

Note that density is the ratio of mass to volume. The formula for this is:

ρ=Vm

Temperature

Now it is common sense that what separates solids from liquids from gases is temperature. Relative to one another, you might assume that a solid is cold, a liquid is warm, and a gas is hot. What is less obvious is what temperature means.

An object's temperature (T) is the average kinetic energy of all its particles. So, the faster particles in an object move, the warmer the object is, and the colder particles in an object, the colder the object is.

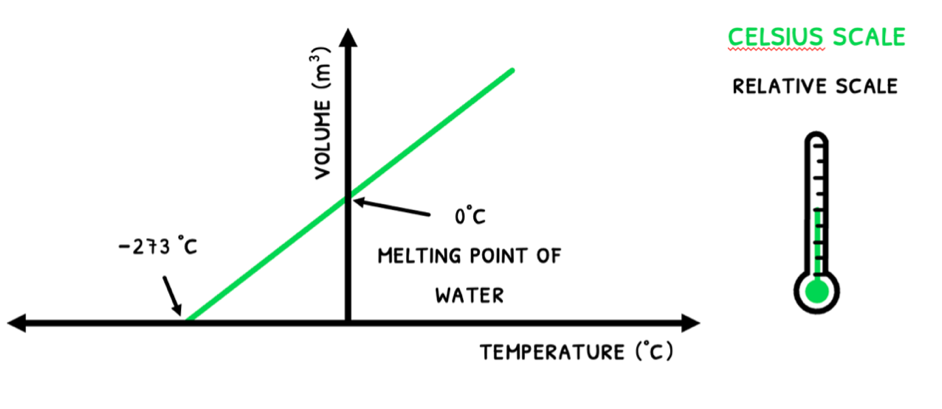

In day-to-day situations, temperature is commonly measured in Celsius (°C). This is a scale based off water, where 0°C is the melting/freezing point of water and 100°C is the boiling/condensing point of water. However, this is not a very scientific way to measure kinetic energy.

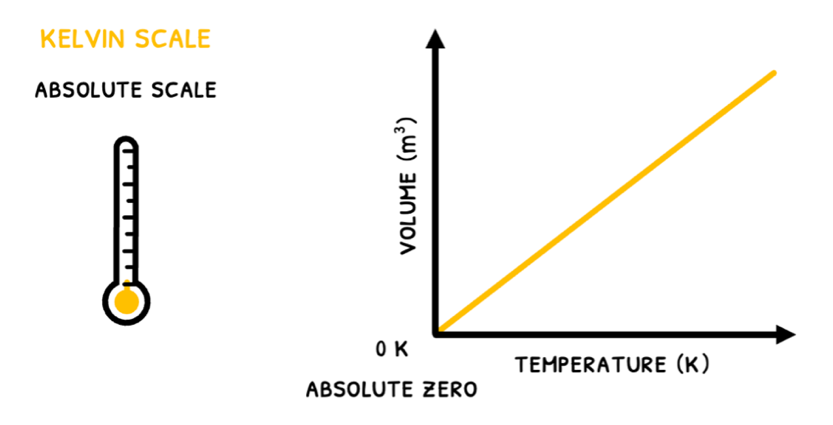

As a result, the Kelvin scale was created. This measures temperature in Kelvin (K), based off 0 K being absolute zero, the coldest possible temperature. At this point, the particle have zero kinetic energy.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B2: The greenhouse effect

Albedo and emissivity

In Topic B.1, you learned about black body radiation. However, it is purely theoretical and mostly applies to stars, so scientists have created additional terms to describe the radiation of everyday objects. These are: albedo and emissivity.

An object’s albedo (α) is the ratio of its reflected radiation power (Pr) to its total incident radiation power (P0). This can also be put in terms of intensity, and as such, the formulae are:

α=P0Pr

α=I0Ir

Sometimes, questions will ask you to calculate the transmitted intensity (It) from an object’s albedo. Two handy formulae for this that are not in your data booklet are:

It=(1−α)I0

Pt=(1−α)P0

An object’s emissivity (e) is the ratio of its emission intensity to the emission intensity of a black body. Thus, for non-black body objects, the Stefan-Boltzmann formula is:

I=eσT4

P=eσAT4

Earth's energy balance

The reason that these aspects of thermal energy transfer are found in this topic is because you need to learn about Earth's energy balance. This can be summarised into three principal sections:

- The sun produces light that is incident on Earth.

- This light is partly reflected and partly absorbed.

- The absorbed light is re-emitted as heat.

Now let's go through this in more detail. The sun’s incident light is termed the solar constant. This is officially defined as the incident solar intensity above Earth’s atmosphere, often given a value of 1360 Wm-2.

You are expected to calculate this intensity your exam from provided values for the:

- Sun’s radius = 6.96 x 108 m

- Distance from the Sun to Earth = 1.50 x 1011 m

- Sun’s surface temperature, 5780 K.

When doing this calculation, assume that the Sun is a perfect black body and use the equation:

P=σAT4

To find the surface area of the sun:

SA = 4πr2

SA = 4π(6.96 x 108)2

SA = 6.09 x 1018 m2

Substituting this and other given values into the equation:

P = (5.67 x 10-8)(6.09 x 1018)(5780)4

P = 3.85 x 1026 W

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B3: Gas laws

Moles

In Topic B.1, you learned about phases, phase changes, and heat transfer of substances. Whilst it is easy to perform experiments measuring these phenomena in solids and liquids due to their finite volume, it completely changes in gases.

The change is that gases cannot easily be measured by their mass or volume. As a result, they are measured in moles (n). This is a measure of the number of particles given by Avogadro’s number (NA) equal to 6.022 x 1023 particles/mole. It relates to the number of particles that would make Carbon-12 exactly 12 grams as the standard element. Therefore, just like one million is 1,000,000, one mole is 6.022 x 1023 particles. For any number of particles (N), to calculate the number of moles, use the formula:

n=NAN

Note that this describes the number of particles so 1 mole of any diatomic molecule, such as H2, has 1.2044 x 1024 atoms because every molecule (and therefore particle) has two component atoms.

The mass of an atom can be expressed as molar mass (M), the mass of one mole of a substance in gmol-1. Calculating molar mass is possible with the formula:

M=nm

Pressure

Once you know how many moles of gas you have, you can then start to analyze its behavior when changing several variables, including pressure, temperature, and volume.

Whilst we know now what temperature is, and the concept of volume is straightforward, we don't know much about what pressure is yet.

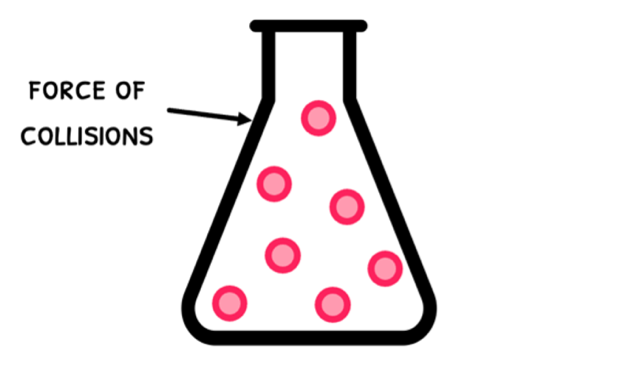

In IB physics, you are supposed to understand that the amount of pressure a gas inside a container experiences is related to the force of the particle collisions with the container walls and the number of collisions per area. To easily digest this concept, think of getting poked and bumped.

- If you get poked softly, you don't feel much pressure. If you get poked hard, suddenly you feel the pressure. The same occurs with particles - collisions with little force don't exert much pressure whereas collisions with high force do exert considerable pressure.

- However, now compare poking and bumping with the same force. A soft bump would result in less pressure than a soft poke because it is spread out over a larger area. The same occurs with particles - less collisions over the same area result in a lower pressure than many collisions over the same area.

Therefore, pressure is the force per unit area of the container. The formula for this is:

P=AF

However, whenever a force is exerted on the container to cause this pressure, the particle transfers energy to the container. This change in energy is related to a change in speed and thus momentum of the particle. As a result, pressure can also be defined in terms of the change of momentum. The formula for this is:

P=31ρv2

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B4: Thermodynamics (HL)

Laws of thermodynamics

In Topic B.1 – B.3, you learned about the basics of thermal energy transfers and gas laws. For HL students, you are expected to know more detail, starting with the four laws of thermodynamics.

- Zeroth law – if two systems are in thermodynamic equilibrium with a third system, then they are in thermodynamic equilibrium with one another. This is a roundabout way of saying that these two systems have the same temperature.

- First law – as per the law of conservation of energy, a closed system exhibiting a change in energy converts this into other forms to maintain total energy. In other words, energy cannot be created nor destroyed, but only changes forms.

- Second law – in a closed system, spontaneous processes are not spontaneously irreversible, and consequently increase the disorder (entropy) of the universe.

- Third law – when an isolated system reaches a temperature of absolute zero, its entropy reaches a constant value.

Within these laws, two terms need to be defined:

- Closed system – a closed system does not allow mass to transfer in or out but allows energy to transfer in and out in the forms of heat or work.

- Isolated system – an isolated system does not allow mass or energy to transfer in or out.

The Zeroth law was effectively covered in B.1, so does not need further evaluation. However, you are expected to know the first and second laws in depth, so let’s cover these one-by-one.

The first law of thermodynamics

The first law essentially rephrases the law of conservation of energy in the context of thermal energy transfer. Here, a few types of energy are at play:

- Heat (Q) – the thermal energy transferred in or out of a system.

- Internal energy (U) – the system’s energy as a sum of its particles’ kinetic energy and the potential energy between particles. Remember that for temperature-dependent changes in internal energy, the formulae are:

ΔU=23NkbΔT=23RnΔT

- Thermodynamic work (W) – the energy exerted on a system by its surroundings (negative) or by a system on its surroundings (positive) that causes a macroscopic force to act on the system. The macroscopic force is quantified by change in volume of the system. Thus, if there is no volume change due to a resultant external force, there is no work being done. The formula for this is:

W=PΔV

The three quantities above are invariably related to one another as the exertion of work by a system on its surroundings would decrease its internal energy, whereas heat supplied to the system increases its internal energy. The formula for this is:

ΔU=Q−W

This equation can be adjusted algebraically to isolate any one of the other two variables. The IB prefers to label it as the heat transfer being equal to the change in internal energy and work exerted. The formula for this is:

Q=ΔU+W

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B5: Current & circuits

Voltage

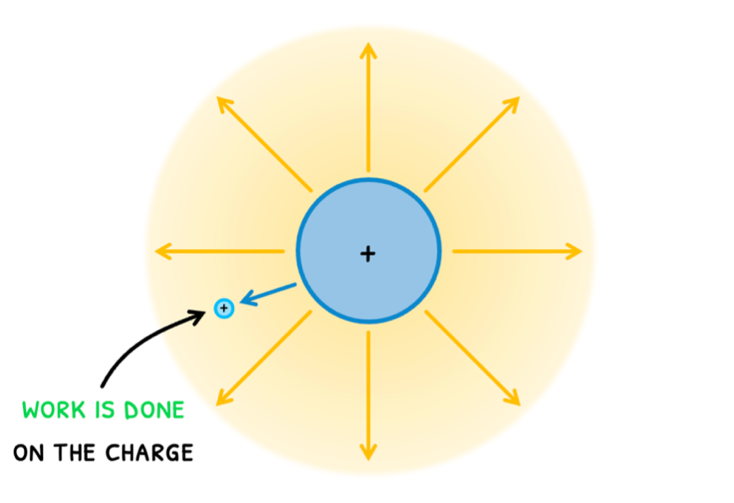

Topic B.5 primarily focuses on electricity, which is the movement of charges. Their movement is brought about by the electric force, and in Topic D.2 you will learn about electric fields that exert this electric force. However, you will learn the basics before this. Remember from Topic A.2 that when an object moves in the direction of an applied force, work is being done on the object. So, if a test charge in an electric field moves in the direction of the exerted electric force, work is done on the charge.

This is the voltage (V), officially defined as the work done per unit charge and measured in Volts (V). The formula for this is:

V=qW

However, voltage typically applies to large scale movements of electrons. When work is done on a single electron, it is measured in electronvolts (eV). To convert, moving an electron through 1 Volt is 1eV, which is equal to 1.6 x 10-19 J.

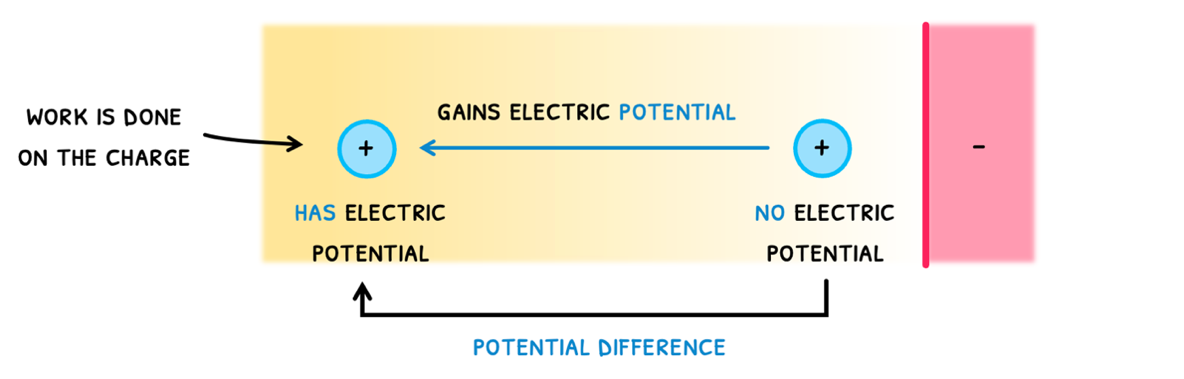

You may also hear voltage referred to as potential difference (pd), and you can use both terms interchangeably. However, let's explain the term nonetheless:

- If you place test charge right next to a charge distribution and then move it, we know that work is being done on the test charge.

- As a result, the test charge gains energy, called its electric potential energy or electric potential.

- Right next to the charge distribution, it had no electric potential, but further away from it, it now has electric potential.

- It is this change in potential that is called the potential difference.

However, this is functionally the same as voltage and thus both terms can be used. It should be noted that potential difference is more often used when discussing individual charge movement, whilst voltage is more often used when discussing circuits.