IB Physics Topic 1 Notes

A1: Kinematics & motion

Properties of motion

In Topic A.1, you need to focus on kinematics - the movement of objects, or motion. This is a fundamental concept in physics, and can be described with several terms:

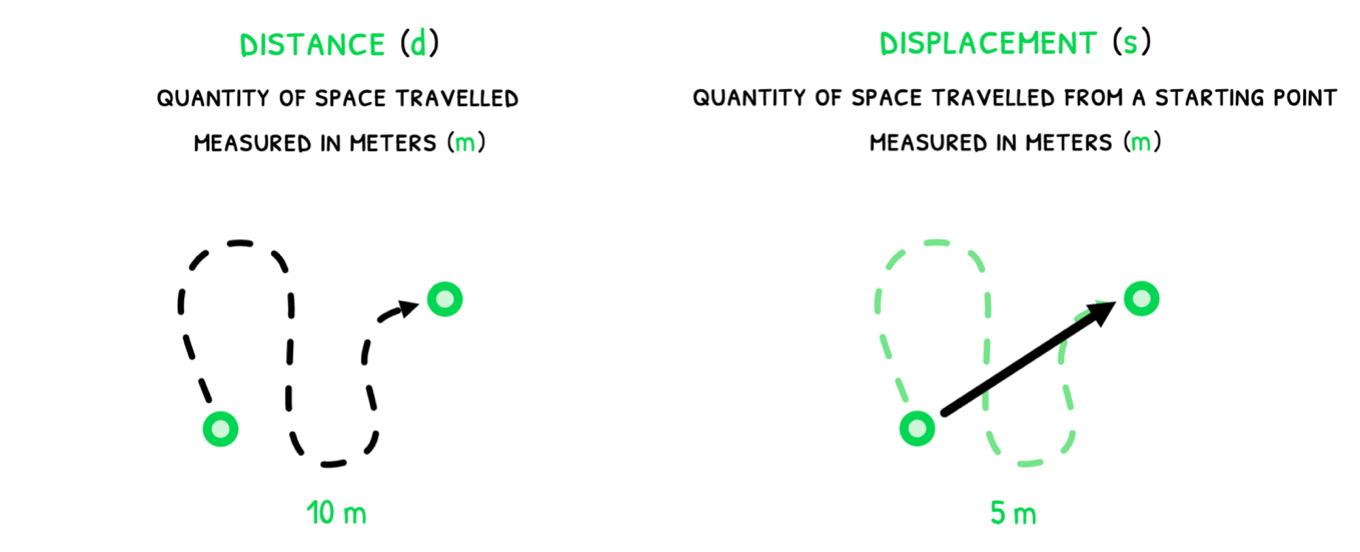

- distance (d) – the amount of space travelled, measured in m.

- displacement (s) – the net distance an object has travelled from its starting point in a direction, measured in m.

- speed (v or u) – the distance travelled per unit time, measured in m s-1. v refers to the final speed and u to the initial speed.

- velocity (v or u) – the displacement per unit time, measured in m s-1. v refers to the final velocity and u to the initial velocity.

- acceleration (a) – the velocity travelled per unit time or displacement travelled per square unit time, measured in m s-2.

The matching equations are:

- velocity (v)=time(t)displacement(s)

- speed (v)=time(t)distance(s)

- acceleration (a)=time (t)velocity (t)=time (t)2displacement (s)

Remember that displacement, velocity, and acceleration are vectors, whereas speed is a scalar and is directionless.

An object’s measured velocity is also dependent on how it is measured and what it is measured in reference to. In motion experiments, velocity or acceleration are measured via:

- light gates – a gate emits a beam of light and can calculate the average speed of the object based on how long it breaks the beam or how long it takes to travel between two gates.

- strobe photography – light flashes at a set rate in front of a camera, capturing the object’s motion in pictures.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

A2: Forces & momentum

Forces

In Topic A.1, the force of gravity and fluid resistance were discussed. In Topic A.2, you need to know more detail about forces and how they impact the motion of objects, including their momentum. Forces are actions that cause the deformation or change in velocity (acceleration) of an object, measured in Newtons (N). Forces act on one object at a time with magnitude and direction and may be exerted by other objects.

The main types of forces encountered are:

- Gravitational (Fg) – the attractive force exerted by an object’s mass on another object, referred to as the affected object’s weight (W).

- Electric (Fe) – the force between two electrically charged objects.

- Magnetic (Fm) – the force between two magnetic objects.

- Normal (FN) – the force a surface perpendicularly exerts on an object due to its weight.

- Friction (Ff) – the force a surface parallelly exerts to counteract another surface’s motion.

- Elastic restoring force (FH) - the force a spring exerts in both directions on another object when it is squished or stretched.

- Tension (T) – the force a rope or cable exerts in both directions on another object when it is stretched.

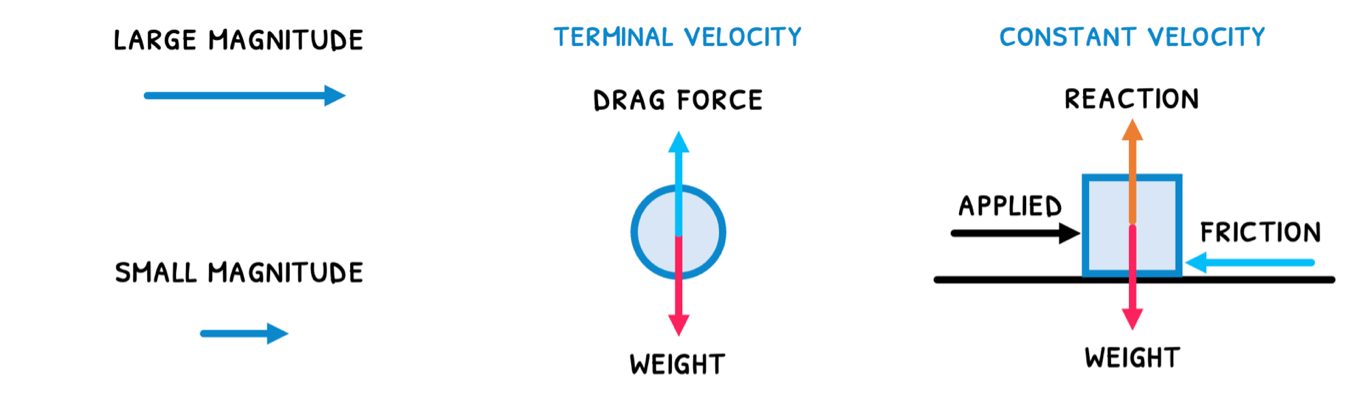

- Viscous drag force (Fd) - the force opposing the motion of a small sphere through a fluid.

- Buoyancy (Fb) - the force on a body due to its displacement of fluid.

Free body diagrams

Forces are drawn using free body diagrams. These show an object and all the forces acting upon it. An example is shown below:

As stated before, weight (W) is the gravitational force on an object, measured in Newtons. This must be distinguished from mass (m), which is the amount of matter contained in an object, measured in kg. The formula for weight, where g = 9.8 ms-2 is:

W=mg

Friction

As stated before, friction is a force exerted by a surface to counteract another surface’s motion. If a surface is said to be smooth, there is no friction between that surface and any surface in relative motion. In friction between solids, there are two types:

Static friction – the force exerted to stop another resting surface from moving. This acts up to a maximum Ff, keeping Σ F = 0. The formula for Ff is:

Ff=μsFN

In this, μs is the coefficient of static friction, which relates the reaction force and the maximum static frictional force. If the applied force > Fs, the object begins to move and Fs decreases, becoming Fd.

Dynamic friction – the force exerted on a moving surface, with a similar formula:

Ff=μdFN

Remember that coefficient of dynamic friction μd < μs. It relates the reaction force and the maximum dynamic frictional force, as described to the formula above.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

A3: Work, energy sources & power

Work

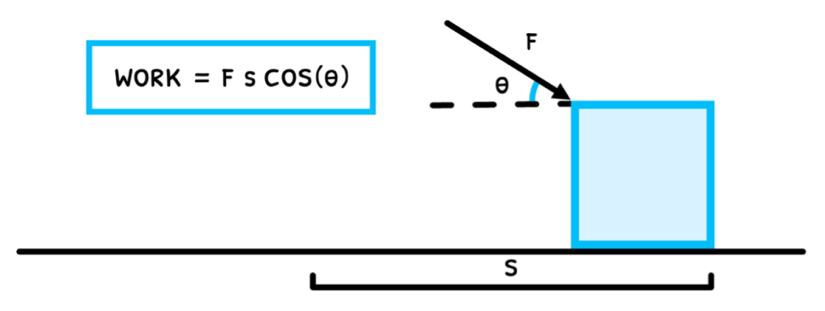

From Topic A.2, you learned about the different types of forces. It may seem obvious that applying any force requires energy, called work. Work (W) is the measure of the energy required to apply a force to move an object in the direction of the force. As such, the formula for this is:

W=Fscosθ

Despite using displacement and force in the formula, work is a scalar quantity. This is because by definition work is only applied in the direction of the force.

As a result, if the object moves at a right angle to the force, no work has been done, as cos (90°) = 0. As with any energy, work is measured in Joules (J).

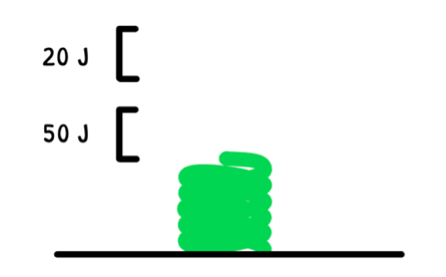

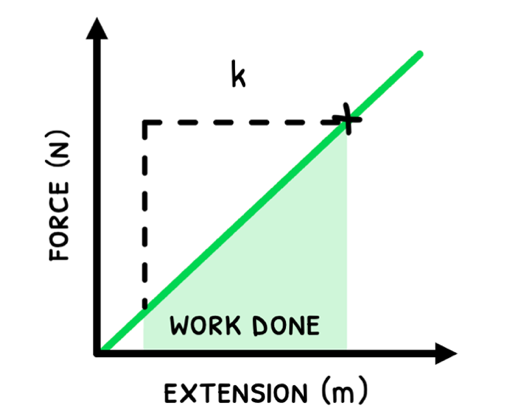

Springs are a special scenario because the work done is not constant. The more a spring is compressed or stretched, the more work is required to compress or stretch it further.

It thus requires a force-distance graph to determine the work, which is the area under the line.

Energy

As mentioned earlier, it takes energy to apply a force. It thus makes that sense that work done is also equal to the amount of energy transferred. Energy (E) is a measure of the amount of work done, measured in joules (J).

Within any physical interaction, the principle of conservation of energy always applies:

- the total energy of any closed system stays the same.

- energy is not created or destroyed, it only changes form.

Most reactions do not have a perfect transfer of energy and will have some transfer into heat and sound.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

A4: Rigid body mechanics (HL)

Translational and rotational motion

In the SL syllabus, the motion of objects is only considered as translational, as movement from one place to another. This applies to the center of mass of an object and describes its motion as one unit, such as a box being pushed on a floor as one unit. Moving as one unit in one direction means that -particles move together and have the same instantaneous velocity.

However, some objects, such as balls and planets, also exhibit rotational motion around their center of mass when they roll or spin on their axis. Spinning around a central axis means that:

- Particles move at different points from the central axis. However, all particles cover the same angle (θ), meaning particles further from the axis cover a greater distance per rotation.

- Thus, particles have the same instantaneous angular velocity (ω), but do not have the same instantaneous linear velocity.

- Particles exhibit centripetal acceleration (ar) towards the axis, called the radial acceleration. Remember that particles have a velocity perpendicular to the acceleration, called the tangential velocity (v). The formulae relating to centripetal acceleration are:

ar=rv2=rω2

- We have always considered objects with uniform circular motion and thus uniform angular velocity. However, if angular velocity changes, particles are said to exhibit angular acceleration (α). This subsequently causes the tangential velocity to change, called tangential acceleration (at). The formula for this is:

at=rα

- The total acceleration of the particles is thus the vector sum of the centripetal and tangential acceleration. The formula for this is:

a=rω4+α2

Comparing the types of motion

Whilst it is important to understand how rotational motion functions, you may be asked to compare and contrast translational and rotational motion. Thus, let’s summarize the key points we have learned so far:

| Type of motion | Translational | Rotational |

|---|---|---|

| Application | To the center of mass | Around an axis of rotation |

| Particle velocity | All have the same instantaneous velocity | All have different instantaneous velocities |

| Particle movement | All move at different points | All move around the same axis |

| Displacement | Linear, measured in meters | Angular, measured in radians |

| Velocity | Rate of change of displacement, measured in ms-1 | Rate of change of angle, measured in rads-1 |

| Acceleration | Rate of change of velocity, measured in ms-2 | Rate of change of angular velocity, measured in rads-2 |

Using these new perspectives of rotational motion, the SUVAT equations that apply to translational motion can be changed as well:

ωf=ωi+αt

ϕ=ωit+21αt2

ωf2=ωi2+2αϕ

ϕ=2(ωf+ωi)t

You will be asked to perform calculations with these rotational SUVAT equations, so make sure you practice questions involving them often!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

A5: Galilean & special relativity (HL)

Frames of reference

In Topic A.1, you learned about the linear and circular motion of objects. Here, it was briefly mentioned that the motion of an object is relative to the observer, such that in two cars travelling at the same speed, the passengers of each do not view the other car as in motion. Thus, we say the motion of an object of often dependent on the frame of reference of the observer. A few more examples of this are:

- A person sitting in a chair may seem motionless.

- However, to the North pole, this person is spinning with the Earth at 460 ms-1.

- To the Sun, this person is orbiting around it at 29.7 kms-1.

- The center of the Milky Way, this person is orbiting it at 230 kms-1.

This can keep going and going. Whilst this may just seem like an illusion of how our eyes perceive motion, it actually forms an entire branch of physics called relativistic physics. In this, you are expected to understand two types: Galilean relativity and special relativity.

Galilean relativity

Galileo developed the theory of Galilean relativity to interpret the same reference frames. The concept is to use the measurements in one frame to work out the measurements in another frame, essentially observing the comparative motion.

The standard example for this is to use two frames (F and F’), which have the directions x, y, and z and x’, y’, and z’, respectively. If a stationary observer (frame F) sees a car with a passenger (frame F’) pass by, we can determine that:

- At any time t, frame F will be stationary and have a velocity of 0.

- At an equal time t’, frame F’ will be moving with a velocity v’.

- When the two graphs are overlaid to show the relative motion, it shows that F’ is moving with velocity v, which is intuitive.

This is a simple scenario because there is only movement in one plane (x-direction) and only one moving frame. However, this becomes more complicated when both observers are moving. Let’s say F is now moving towards F’.

- At any time t, frame F have a velocity of u.

- At an equal time t’, frame F’ will be moving with a velocity v.

- When the two graphs are overlaid to show the relative motion, it shows that relative to one another, F and F’ are moving at a velocity of u-v. Thus:

u′=u−v

To calculate their x-positions relative to one another, the formula used is:

x′=x−vt