IB Chemistry Topic 5 & 15 Notes

R2.1: Amount of change

Chemical reactions

Within chemistry, we look at substances undergoing chemical reactions, reactions that form new substances by breaking bonds in the reactants and forming bonds in the products. This causes an energy change in the system but conserves mass and particles. The aim for each reaction is to reach the highest possible desired product yield.

Balancing Equations

The first step in considering any chemistry problem is to make sure a chemical reaction is balanced. This means that in every chemical reaction the number of atoms of every element in the reactants must be the same as in the products.

In order to balance an equation, coefficients can be changed or added in front of certain species. Balanced equations also include state symbols in brackets behind species. These include: (s), (l), (g) and (aq), as shown below:

CaCO3 (s) + HNO3 (aq) → Ca(NO3)2 (aq) + CO2 (g) + H2O (l)

An effective order for balancing equations is as follows:

- Balance the metallic elements.

- Balance the next element that only occurs once on each side.

- Balance the rest of the elements (if required).

At the end, the balanced equation becomes:

CaCO3 (s) + 2HNO3 (aq) → Ca(NO3)2 (aq) + CO2 (g) + H2O (l)

This is only a rough guide and difficult equations will require practice to master!

Basics of reactions

Now that you know how to balance an equation, let's cover the basics of reactions by breaking down our equation.

CaCO3 (s) + 2HNO3 (aq) → Ca(NO3)2 (aq) + CO2 (g) + H2O (l)

- Reactants - the species undergoing the reaction. In this case, these are CaCO3 and HNO3.

- Products - the species produced at the end of the reaction. In this case, these are Ca(NO3)2, CO2, and H2O.

- Molar ratio - this is the ratio between any two species in the reaction. For example, the molar ratio of CaCO3 to HNO3 is 1:2 and the molar ratio of CaCO3 and Ca(NO3)2 is 1:1.

As you can see, the molar ratio thus guides how much of each species is involved in the reaction. In real life, this will not always occur, either accidentally or purposefully - meaning that actual amounts of reactants will not follow the molar ratio.

This means each reagent takes one of two forms:

- Limiting reagent - this is the reagent with the moles leading to the smallest molar ratio.

- Excess reagent - naturally, this is any other reagent, which has more moles than the smallest molar ratio.

Sail through the IB!

R2.2: Rate of change

Rate of Reactions

Now that you understand atoms, molecular structure, and how energy changes during reactions, you can focus on the reactions themselves. In Topic R2.2, you start this by focusing on the rate of reaction. This is simply the speed at which a reaction occurs and can be thought in a few ways:

- The increase of concentration/mass/volume of products over time.

- The decrease of concentration/mass/volume of reactants over time.

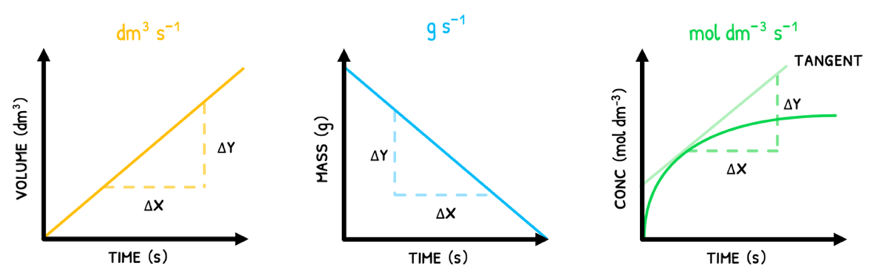

As a result, the units of rate can be mol dm-3 s-1, g s-1 or dm3 s-1. However, mol dm-3 s-1 is the standard unit of measurement for rate.

This is typically represented graphically with volume/mass/concentration on the y-axis and time on the x-axis. In these:

- In straight-line graphs, the rate at any time point is equal to the slope of the line.

- In curved-line graphs, the rate at any time point is equal to the slope of the tangent.

Note that products will show a positive slope because they are produced throughout the reaction whereas reactants will show a negative slope because they are used up throughout the reaction.

Collision Theory

Before learning more about rates, it is essential to understand the basics of molecular movement. Particles in a substance will vibrate or move randomly in space and collide with one another frequently. When certain criteria are met, a collision results in a reaction:

- Correct geometry

- Correct orientation

- Sufficient kinetic energy

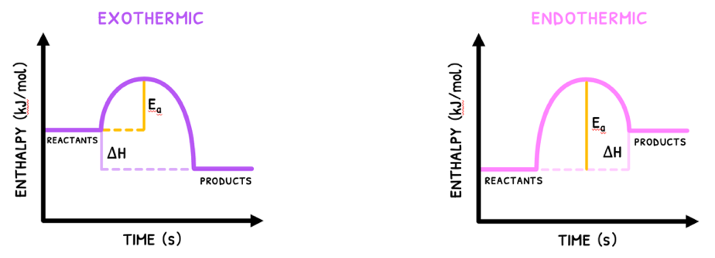

Activation Energy

The last criteria is very important, because this is the factor that most determines whether a reaction will or will not occur. It is termed the activation energy (Ea) and is defined as the minimum energy required for two particles to successfully collide and produce a reaction.

Although this may be a new term, it has appeared before in enthalpy diagrams. In these, the curve from reactants to products indicates the activation energy.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

R2.2: Further rate of change (HL)

Rate Expression

Now that you know basics of rates and the factors that impact it, in the HL syllabus you need to be able to quantify rate and perform calculations.

Let's start by looking at the rate expression, which is used to determine the rate of a reaction at a specific temperature based on the concentration of the reactants. For a two reactant system, the formula is:

Rate=k[A]x[B]y

Note that this is different to a rate equation, which can only be determined with experimental data.

In this:

- [A] is the concentration of reactant A.

- [B] is the concentration of reactant B.

- k is the rate constant.

- x is the order of reactant A.

- y is the order of reactant B.

Whilst [A] and [B] are obvious, the rest are new, so let's cover them.

Rate Constant

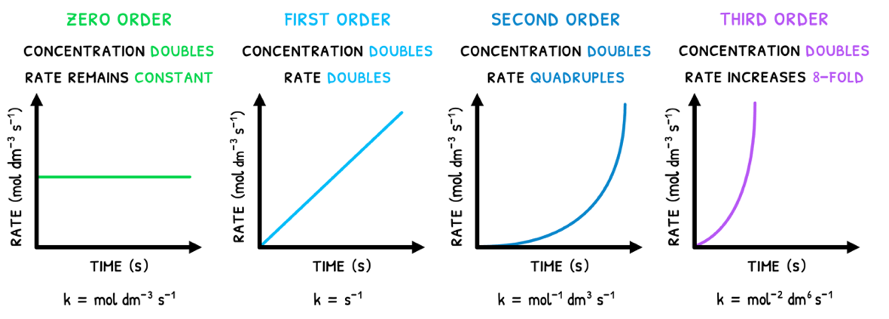

The rate constant reflects the rate at a certain temperature, and thus changes as temperature changes. The units used for k depend on the reaction order, so let's cover this.

Reactant Order

For this we start with reactant order, which is the degree to which a reactant's concentration impacts rate. There are four orders to remember:

- Zero order - this reactant does not influence rate. Thus, if concentration doubles, rate remains the same.

- First order - this reactant is directly proportional to rate. Thus, if concentration doubles, rate doubles.

- Second order - this reactant is exponentially proportional to rate. Thus, if concentration doubles, rate quadruples.

- Third order - this reactant is cubically proportional to rate. Thus, if concentration doubles, rate octuples.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

R2.3: Extent of change

Properties and Types of Equilibrium

In Topic R1.1 you learned about reaction kinetics and in Topic R2.2 you learned about reaction rate. As mentioned in those topics, once a reaction is complete, it reaches a state of equilibrium.

Equilibrium is defined as the position of a reaction in which the concentration of both the products and reactants remains constant. The position of equilibrium varies for every reaction, as in some it lies closer to the reactants and in others closer to the products.

There are a few important properties of equilibrium:

- It can only be obtained in a closed system. This means the reactants and products can't exit into the surroundings.

- There are no overall changes in concentration.

- The concentrations of reactants and products are not necessarily the same.

Before discussing the types of equilibrium, you need to review the types of reactions:

- Non-reversible reactions - reactions that only occur forwards to convert reactants to products.

- Reversible reactions - reactions that occur forwards to convert reactants to products and reverse to convert products to reactants.

In these reactions, two types of equilibrium can occur:

- Static equilibrium - in this, the rate of forwards reaction reaches zero.

- Dynamic equilibrium - in this, the rate of the forwards reaction equals the rate of the reverse reaction.

An additional types of equilibrium is phase equilibrium. This is an equilibrium between phase changes. For example:

Br2(l) ⇌ Br2(g)

In dynamic and phase equilibria, despite forwards and reverse reactions, the overall concentrations of reactants and products remain the same.

Equilibrium Constant

You are expected to be able to quantify the position of equilibrium, which is done by the equilibrium constant Kc. In the reaction:

aW + bX ⇌ cY + dZ

The formula for this is:

Kc=[W]a[X]b[Y]c[Z]d

As you can see, this places the concentration of products as the numerator and concentration of reactants as the denominator.

Thus:

- Equilibrium lies close to the products - this means the container is mostly products and so Kc > 1.

- Equilibrium lies close to the reactants - this means the container is mostly reactants and so Kc < 1.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

R2.3: Further extent of change (HL)

Reaction Quotient

Now you can see how the equilibrium constant is the ratio of rate expressions. As a result, the formula only applies when the system is at equilibrium. If it has not reached this point yet, it is still in the reaction and the same formula describes the reaction quotient (Q). So in the reaction:

aW + bX ⇌ cY + dZ

The formula for this is:

Q=[W]a[X]b[Y]c[Z]d

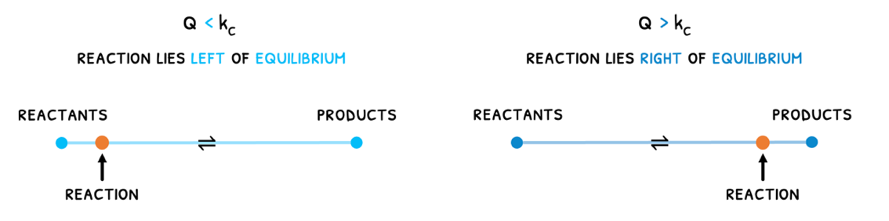

The reaction quotient describes where the reaction lies with respect to the equilibrium.

- If Q < Kc, it means the reaction still has more reactants and is undergoing a forwards reaction to produce more products and reach equilibrium.

- If Q > Kc, it means the reaction still has more products and is undergoing a reverse reaction to produce more reactants and reach equilibrium.

Lastly, if Q = Kc, it means equilibrium has been reached.

Equilibrium Calculations

Secondary to the concept of the reaction quotient, you are expected to be able to perform calculations for the equilibrium positions using concentration data.

This method requires the initial concentration, change in concentration, and equilibrium concentration, a trio of information known as ICE. These are typically shown in an ICE table for easy calculation of changes. This is shown below for a reaction:

X2 + Y2 ⇌ 2XY

| X2 | Y2 | XY | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | a | b | c |

| Change | -x | -x | +2x |

| Equilibrium | a-x | b-x | c+2x |

Once the moles at equilibrium have been found, divide by volume to find concentration and use the Kc formula. It's that simple.