IB Chemistry Topic 4 & 14 Notes

R1.1: Enthalpy

Heat

In Topic S1.1, you learned that bond formation and breaking requires or releases energy. In this topic, you learn how to understand why this occurs and calculate the associated energy changes, particularly in relation to the heating of substances.

Remember that temperature is the average kinetic energy of particles. From this, you can appreciate that when fast particles from hot objects react with slow particles from cold objects, they exchange energy. Heat (Q) is thus the thermal energy transferred between two objects with different temperatures.

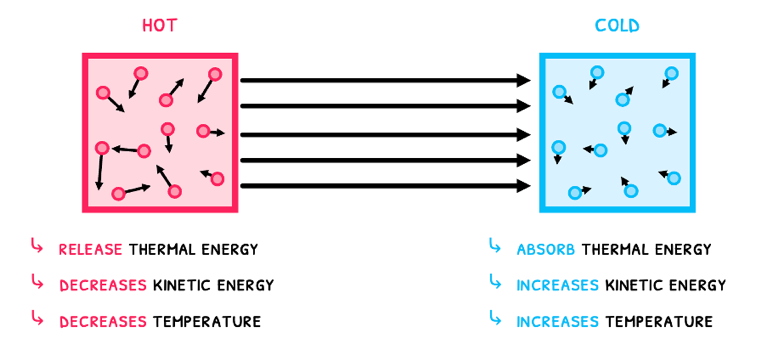

Since the faster particles tend to give up energy during collisions, heat naturally flows from hot objects to cold objects, or high temperatures to low temperatures. During this:

- Hot objects release thermal energy, which decreases the kinetic energy of their particles. As a result, their temperature decreases.

- Cold objects absorb thermal energy, which increases the kinetic energy of their particles. As a result, their temperature increases.

Enthalpy and Enthalpy Change

However, the kinetic energy of a particle is not the only energy it possesses. It also contains chemical energy in the form of intramolecular and intermolecular bonds. The total internal energy of the particle is thus the sum of the kinetic and chemical energy of particles, termed the enthalpy (H).

However, a particle's enthalpy cannot be measured, so we instead calculate the enthalpy change (ΔH) in kJmol-1, which is equal to the heat transfer.

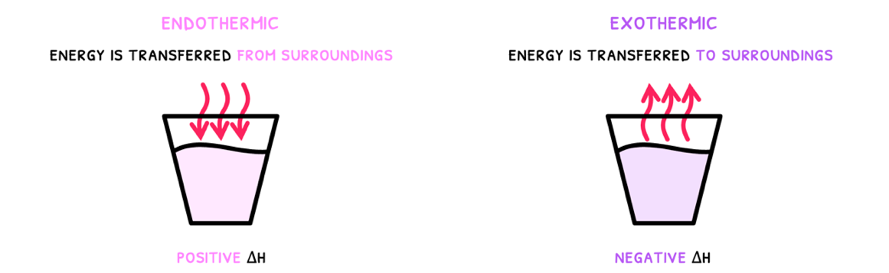

As a result, two types of enthalpy changes are possible: negative and positive. This is dependent on the type of reaction:

- Exothermic - a reaction that transfers energy to the surroundings, releasing it. This has a -ΔH and a decrease in temperature. The products of this reaction are thus lower in energy and more stable.

- Endothermic - a reaction that transfers energy from the surroundings, absorbing it. This has a +ΔH and an increase in temperature. The products of this reaction are thus higher in energy and more unstable.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

R1.2: Cycles of energy

Hess's Law

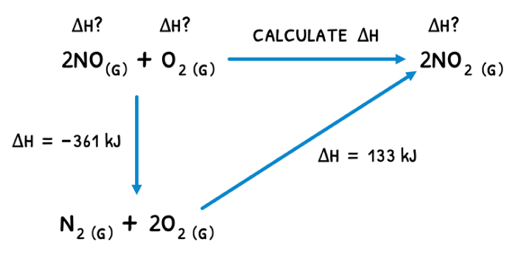

In Topic R1.1, you learned about enthalpy change and how to measure it for exothermic reactions using a calorimeter. Whilst there are other ways to directly measure enthalpy changes, it is not always possible for every reaction. For this, another method is needed.

Hess's law describes that the enthalpy changes of a reaction is independent of the pathway between the initial and final states. This means that:

- From A to C, an enthalpy change of 10 kJ mol-1 may be observed.

- From A to B to C, the same end result was achieved and thus the overall enthalpy change is 10 kJ mol-1.

By breaking down a reaction into two sub-reactions, a reaction triangle can be formed and the unknown enthalpy change for the target reaction calculated.

Bond Enthalpies

Whilst Hess's law is an effective method to calculate enthalpy changes, it is also not always applicable. This leaves a last resort method - bond enthalpies.

Remember that energy is stored in chemical bonds. The bonds of interest are typically covalent bonds, which we know are impacted by bond length, bond strength, and bond polarity. The bond enthalpy is thus defined as the enthalpy change when one mole of covalent bonds is broken in a gaseous molecule. The formula for this is:

ΔH=ΔHbonds broken−ΔHbonds formed

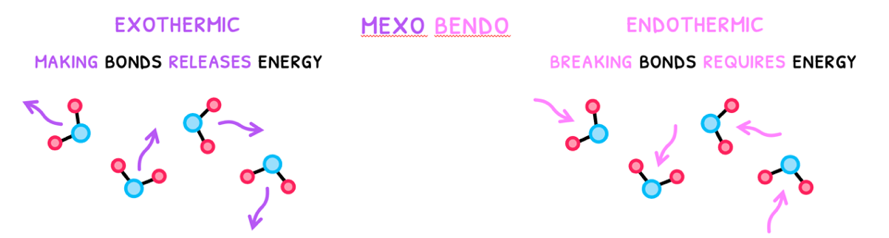

In this context, the important concept to understand is the enthalpy change that occurs during bond formation and breaking.

- Bond formation releases energy. This thus has a -ΔH and is an exothermic reaction.

- Bond breaking requires energy. This thus has a +ΔH and is an endothermic reaction.

To remember which is which, use the phrase MExo BEndo (Making bonds is Exothermic, Breaking bonds is Endothermic).

Average Bond Enthalpy

However, as stated before, the bond enthalpy changes with bond length and bond strength. For example, moving from single to triple bonds will increase the amount of energy required to break the bond. Moving from single to triple bonds also decreases the bond length, hence a decrease in bond length increases the bond strength. This will all result in differences in the values of bond enthalpy.

The values in your data booklet are average bond enthalpies. These are calculated averages of bond enthalpies from a variety of gaseous compounds of which the specific bonds have been broken and the enthalpy measured. This means theoretical calculations using them will never exactly match literature measurements of enthalpy change, especially when using bond enthalpies for aqueous, liquid, or solid compounds.

R1.2: Further energy cycles (HL)

Types of Enthalpy

You previously learned about the standard enthalpy change of a reaction (ΔHø). Remember that the formula for this is:

ΔH=ΔHproducts−ΔHreactants

However, in the HL syllabus, you need to appreciate that this is an umbrella term used to describe the enthalpy change that occurs during any reaction. However, there are seven main subtypes you need to be aware of:

Standard enthalpy change of formation (ΔHøf) - this is the enthalpy change when one mol of a substance forms from its constituent elements in their standard states at STP. For example:

C(s) + O2 (g) → CO2 (g)

Note if O2 was liquid, this would not be at STP and thus incorrect. Additionally the formation of any element by itself has no enthalpy change! For example:

O + O → O2 ΔHøf = 0 kJmol-1

Standard enthalpy change of combustion (ΔHøc) - this is the enthalpy change when one mol of a substance completely burns in oxygen at STP. For example:

CH4 + 2O2 → CO2 + 2H2O

Standard enthalpy change of neutralization (ΔHøn) - this is the enthalpy change when one mol of water is produced when an acid reacts with an alkali at STP. For eaxmple:

NaOH + HCl → NaCl + H2O the you learned about three types of enthalpy change. In the HL curriculum, you need to learn an additional six types:

Standard enthalpy change of atomization (ΔHøhyd) – this is the enthalpy change when one mole of gaseous atoms are formed from its element in its standard state. This is typically highly endothermic. For example:

Li(S) → Li(g) or 0.5Cl2(g) → Cl(g)

Standard lattice enthalpy change (ΔHølatt) – this is the enthalpy change when one mole of a solid ionic lattice is broken into its individual gaseous ions. This process is endothermic. For example:

BeF2 (s) → Be2+(g) + 2F-(g)

Ionization energy (ΔHøie) – Remember that this is the enthalpy change when one mole of electrons are removed from one mole of gaseous atoms. For example:

Na(g) → Na+(g) + e-

Electron affinity (ΔHøea) – Remember that this is the enthalpy change when one mole of electrons is added to one mole of gaseous atoms. It is usually an exothermic reaction. For example:

Ca2+(g) + e- → Ca+(g).

Enthalpy of Aqueous Solutions

An additional two types of enthalpy changes are used in a separate energy cycle relating to aqueous solutions. These are:

Standard enthalpy change of hydration (ΔHøhyd) - this is enthalpy change when one mole of gaseous ions are dissolved in water to form an infinitely dilute solution. It is always exothermic. For example:

Cl-(g) → Cl-(aq)

Standard enthalpy change of solution (ΔHøsol) - this is the enthalpy change when one mole of a solute is dissolved in excess pure solvent. This is typically highly endothermic. For example:

LiBr(s) → Li+(aq) + Br-(aq)

Sail through the IB!

R1.3: Fuels

Energy from fuels

We use fuels everywhere such as to power our cars and our homes. Fuels, which are typically hydrocarbons, such as coal, oil or gas release energy to provide us with the necessary heat and power via complete combustion. This is a highly exothermic reaction that produces heat and requires oxygen. Complete combustion of fuels occurs with excess oxygen and produces carbon dioxide and water. For example, pentane (C5H12) combusts as follows:

C5H12 + 8O2 → 5CO2 + 6H2O

Alcohols can also undergo complete combustion under the same conditions to form Carbon Dioxide and water. For example, Ethanol (C2H5OH) combusts as follows:

C2H5OH + 3O2 → 2CO2 + 3H2O

When oxygen is limited, combustion is called incomplete. The products of incomplete combustion are Carbon (soot), carbon monoxide and water. The IB wants you to determine equations for the incomplete combustion of alcohols and hydrocarbons. The products of the reaction are identical, only the balancing has to be practiced.

Methane:

3CH4 + 4O2 → C + 2CO + 6H2O

Ethanol:

C2H5OH + 2O2 → 2CO + 3C (soot) + 3H2O

Carbon monoxide is an incredibly poisonous gas and incomplete combustion can therefore be detrimental to health. Carbon monoxide can bind to haemoglobin and limit oxygen supply to organs.

Fossil fuels

Most fuels that we burn to create energy are fossil fuels. These include gas, oil and coal. These fuels have various environmental concerns including the production of CO2 through combustion, which is a greenhouse gas and contributes to global warming.

To determine the amount of carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere when different fuels burn we can use stoichiometric values of the combustion reactions. The fossil fuels the IB requires you to know are coal, crude oil and natural gas.

Coal - this is primarily made of carbon with variable levels of sulphur, oxygen or other impurities. Its high carbon content makes it very prone to incomplete combustion if oxygen levels are not high enough. Complete combustion looks as follows:

C(s) + O2 (g) → CO2 (g)

- Crude oil - this is composed of a variety of hydrocarbons such as alkanes and alkenes with other elements such as sulphur and nitrogen. The presence of impurities can contribute to its likelihood to undergo incomplete combustion.

- Natural gas - this is primarily composed of methane with varying levels of propane and ethane. Combustion of natural gas is generally efficient but incomplete combustion can still produce carbon monoxide and other harmful substances. Natural gas has the highest energy density.

Biofuels

Biofuels are plant-based fuel sources. These are being harnessed as an alternative fuel source than fossil fuel sources. Biofuels include ethanol and biodiesel.

They are produced by the biological fixation of carbon in a short time frame through photosynthesis.

The equation for photosynthesis is:

6CO2 + 6H2O → C6H12O6 + 6O2

Ethanol is produced from glucose via fermentation:

C6H12O6 → 2C2H5OH + 2CO2

Ethanol as a biofuel is carbon neutral as the CO2 produced during fermentation is also used up in the photosynthesis process.

The advantages of ethanol are:

- Sustainable source of energy through consistent use of carbon dioxide emitted

- Widely distributed all over the world

Disadvantages of ethanol are:

- Ethanol fuel itself is toxic which requires care in use

- The fuel efficiency in high ethanol percentage blends is lower than regular fuels

- Biofuels also require more agricultural development, which could strain land and water resources.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

R1.4: Entropy & Spontaneity (HL)

Spontaneity

In Topic R1, you learned more about enthalpy changes and in general, you have learned about how exothermic and endothermic reactions change the stability of chemical compounds. The next component you need to know is how this stability reflects the likelihood of a reaction occurring, termed spontaneity.

A spontaneous reaction is a reaction that occurs without energy input. However, both exothermic and endothermic reactions can be spontaneous even though endothermic reactions typically require an energy input. This is because spontaneity depends on three factors:

- Enthalpy

- Temperature

- Entropy

Entropy and Entropy Change

The last factor is new, so let's cover it. Entropy (S) is colloquially known as a measure of the disorder of energy. Officially, it is a measure of distribution of available energy among particles, measured in J K-1 mol-1.

Just as with enthalpy, entropy cannot directly be measured, but changes in entropy can. Therefore, the standard entropy change (ΔSø) is used for reactions. The formula for this is:

ΔS=ΔSproducts−ΔSreactants

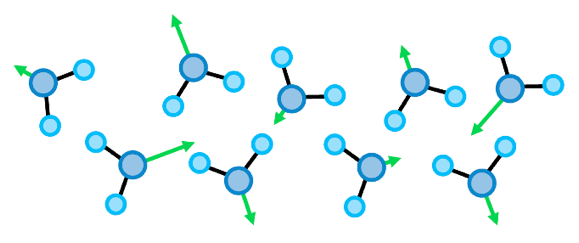

Whilst it is easy to understand how enthalpy changes can be determined, it is less obvious with entropy. A way to think of entropy is that systems with a greater distribution of energy have a higher disorder and thus a higher entropy.

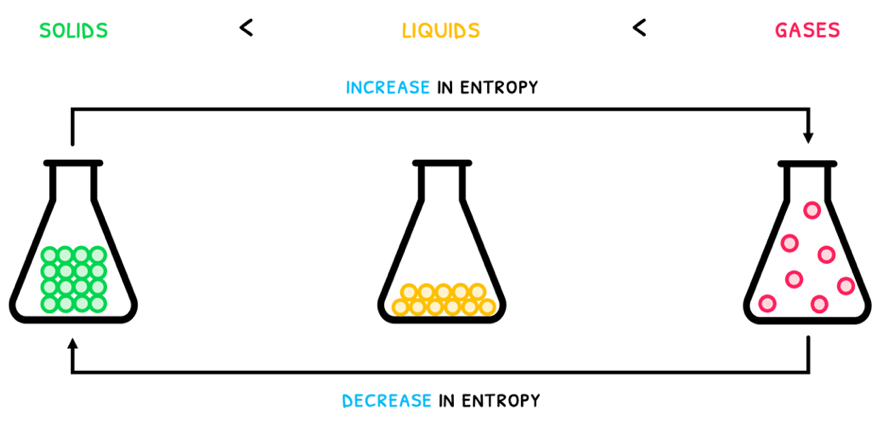

This can easily be seen as substances progress from solids to liquids to gases. As a solid, the particles are in very organized structure and as a gas, the particles have no organized structure and randomly move.

Thus, from solids to gases, entropy increases and so the entropy change is positive. From gases down to to solids, entropy decreases and so the entropy change is negative.