IB Biology Topic 4 Notes

A4.1: Evolution & speciation

Evolution

Topic 4 focuses on ecosystems and changes within them. In the context of organisms, the changes they undergo are mostly due to evolution. This is the change in heritable characteristics of a species over time.

Given evolution's previously controversial history since its proposition of theory in the mid 19th-century by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, it is important to understand the process.

The theory of evolution by natural selection is governed by four tenets:

- More offspring are produced than can survive.

- Morphology, physiology, and behavior greatly varies between individuals.

- Different traits results in different rates of survival and reproduction.

- Traits are passed down generations.

Evidence for evolution

The evidence for evolution is provided by several key pieces of information, including:

- Base sequences

- The fossil record

- Selective breeding

- Homologous structures

Base sequences are the most used evidence for evolution. RNA and DNA base sequences or amino acid sequences in proteins can be determined in any species, and taken from fossils. This allows scientists to relate species together on the basis of how different these base sequences are and determine how long ago two species shared a common ancestor. Since this is such a powerful tool, sequence data is the most relied upon evidence of common ancestry.

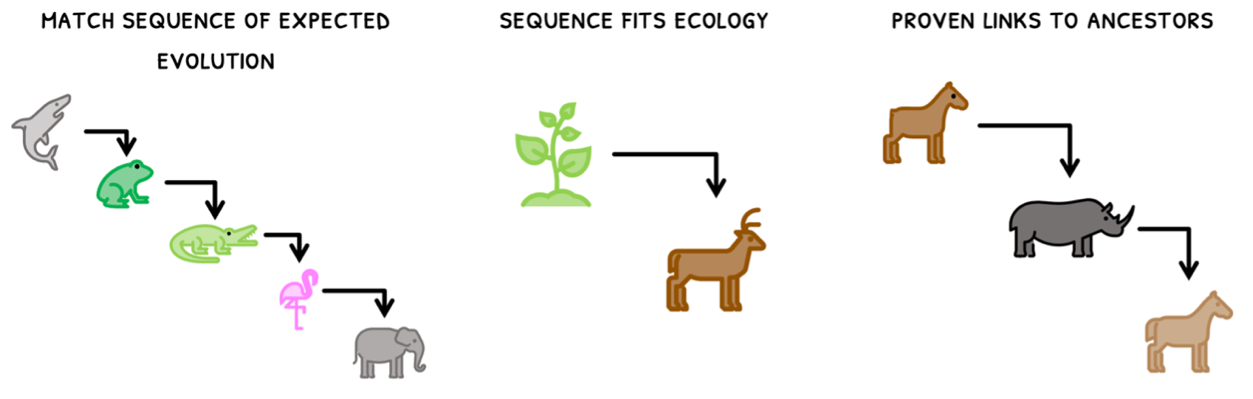

The fossil record supports evolution for four reasons:

- The fossil record shows a sequence of expected developing complexity over time. For example, from to fish to amphibians to reptiles to birds to mammals.

- This sequence also matches the ecology. For example, plants appeared before animals adapted to survive on plants appeared.

- Many existing species have proven links to their ancestors. For example horses formed from rhinos, which formed from Hyracotherium.

- Additionally, it suggests that many species no longer exist, suggesting a change in organisms over time.

Selective breeding is the process by which organisms with desired characteristics are selected and bred together. This mostly occurs in domesticated animals, such as cows or horses, and is also called artificial selection.

It supports evolution because:

- It shows how the heritable characteristics of a species can change over time.

- Sometimes, it is even able to form new species.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

A4.1: Further speciation (HL)

Types of speciation

At this point, you have heard of reproductive isolation leading to speciation a few times. You need to understand that the type of isolation influences the type of speciation:

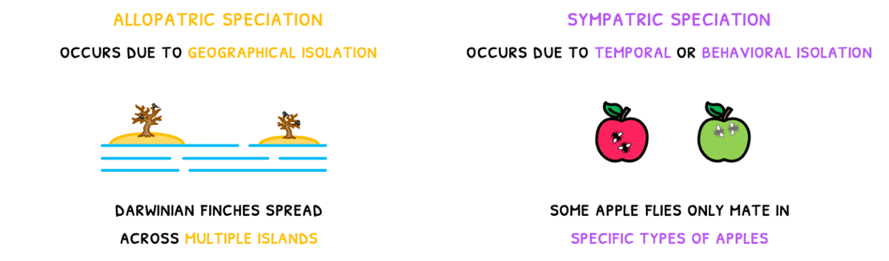

- Allopatric speciation - this is speciation that occurs due to geographical isolation. An example would be the Darwinian finches, spread across multiple islands. Interestingly, this therefore creates multiple gene pools for a single species.

- Sympatric speciation - this is speciation that occurs due to temporal or behavioural isolation. An example would be apple flies, where the hawthorn and non-hawthorn varieties only mate in specific types of apples, despite living in the same area.

The type of isolation influences how and how long speciation occurs for, but eventually the two populations evolve to exhibit different characteristics. Over a sufficient time period, the two populations cannot interbreed to produce fertile offspring, and are thus classed as two different species.

Adaptive radiation

As a result of reproductive isolation, it is evident that species may develop into radically different organisms, even if they live in the same area. This normally occurs via adaptive radiation. Remember that this is the evolution of homologous structures for different function, such as the pentadactyl limb in whales for swimming and bats for flying.

The important concept to remember is that if two species speciate within the same area, they still compete with one another for resources. If there are vacant niches present within the community, the species that is outcompeted is more likely to undergo adaptive radiation and fill this niche. As a result, the two separated species can co-exist in the same ecosystem and increase its biodiversity!

Hybridization

However, equally important in speciation is the maintenance of reproductive isolation. Hybridization is the production of offspring from two different species. In closely related species there are mechanisms that maintain reproductive isolation after fertilization, called post-zygotic isolating mechanisms. There are two main methods to consider:

Hybrid inviability

This method aims to impede zygotic development. Thus, when a zygote is produced, its genetic incompatibility may arrest its development. This can occur due to different chromosome numbers between the two species, such as sheep and goats. Sheep have 54 chromosomes, and goats 60 chromosomes so if they mate, any offspring are typically stillborn.

Hybrid sterility

If two species mate and can produce offspring, the species may be reproductively isolated if the offspring produced are sterile. This is seen in mules, the product of a horse and a donkey and in zebronkeys the product of a cross between a zebra and a donkey. This cannot continue the genetic line and effectively halts hybridization.

Sail through the IB!

A4.2: Conservation of biodiversity

Biodiversity

Biodiversity is a commonly discussed concept in the media, but few know what it actually means. By definition, biodiversity refers to the variety of life on Earth and is divided into three subtypes:

- Genetic diversity - the number of different genetic characteristics within a species. Species with a high genetic biodiversity tend to survive better and be less susceptible to disease.

Species diversity (species richness) - the number of different species existing in a given community and their species awareness or their relative abundance. Stable ecosystems usually possess a high species diversity.

Ecosystem diversity - the number of different habitats, communities, and ecological niches within an ecosystem at a given location. This typically includes the ecosystem's impact on humans and the environment.

Since biodiversity is commonly used to track the status of an ecosystem or community, it must have some importance. It is estimated that 8 million species currently exist on earth, the highest number of species alive on Earth than at any previous time. However, this number is likely inaccurate as less than 20% of organisms have been identified and most of these unknown species are most likely invertebrates that are difficult to find.

On the other hand, it is also possible that historical biodiversity is underestimated. We know that there is much phenotypic variation between individuals of the same species within the same population. Such differences are even more apparent between males and females, and in individuals of different ages. Use of equipment that permits genetic analysis allows for accurate classification confirmation of live species, but this is more difficult in extinct species. Thus, classification in such cases is reliant exclusively on morphology, which can occur in two ways:

Splitting - each new fossil showing any difference from those already classified is designated as a new species.

Lumping - each fossil with a slight difference from one already classified is grouped with the existing classification.

For example, when five hominid skulls were found in a cave in the Republic of Georgia, all with slight differences, it was initially deemed to be evidence of multiple species having occupied the same location, employing the splitting approach. Another group of scientists, bearing the concept of niche exclusivity in mind hypothesised that the five skulls where actually all of the same species, and lumped them together. Their explanation for the minor differences between the skulls was that a similar range of variation is apparent in today’s modern day ape species and humans. Thus, lumping of fossils may result in a lower biodiversity than was actually present.

Mass extinction events

On the other hand, it has been calculated 99% of all species to have ever existed on this planet are already extinct. The majority of these are thought to have died during mass extinction events. There have been five such mass extinction events since the first organisms developed around 3.5 million years ago, with the sixth said to be occurring right now.

This current sixth mass extinction is attributed to anthropogenic causes, such as unsustainable use of energy, land, and water, as well as climate change. As a result, it is estimated that one species per million per year becomes extinct. These extinction rates are estimated using background extinction rates as a reference comparison. You are expected to remember the extinction of three species:

The North Island Moa

In New Zealand, the North Island Moa (Dinornis novae-zelandiae) is a large flightless herbivore that went extinct 600 years ago. The extinction occurred within 150 years of the arrival of human settlers to New Zealand from Polynesia, referred to as the Moa Hunter period. The activities of the settlers, hunting, gathering eggs, burning down areas to repurpose the land and the introduction of predators underpin the Moa's extinction.

The Caribbean Monk Seal

Once widely distributed across the Caribbean, the Caribbean Monk Seal populations were in the hundreds of thousands. European immigration to the area brought seal hunting with it. Thus, between the 17th and 19th centuries, huge numbers of monk seal were killed for their meat and oil, leading to the species' extinction by the 1950’s.

- The last example will be of your teacher's choice.

However, rapid extinctions such as above also provide an insight into the Quaternary megafauna extinction 10,000-50,000 years ago. During this time, 178 species of mammals, including giant kangaroos, mammoth and ground sloth vanished. It is believed that the arrival of humans in certain regions correlate with these events. Thus, any rapid extinction event, such as the dodo, will suffice.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B4.1: Adaptations

Habitats

Next up, you need to learn about habitats and how organisms make a living in an ecosystem. A habitat is officially defined as the place where a community, species, or organism lives. This can typically be described by the geographical and physical location and the type of ecosystem.

Each habitat is thus defined by its abiotic factors. To understand this, remember that ecosystems are composed of two types of factors:

- Biotic factors - these are living things, such as animals, plants, or bacteria.

- Abiotic factors - these are non-living things, such as water, air, and the sun.

Biotic factors can be further sub-divided into three categories:

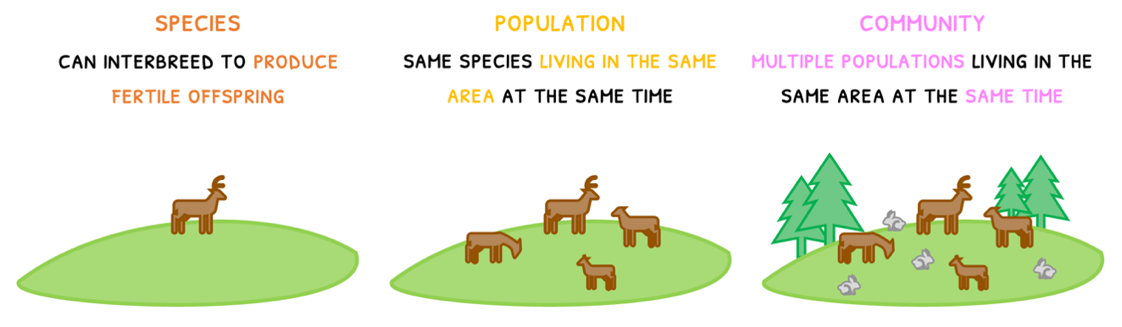

- Species - a group of organisms that can produce fertile offspring.

- Population - a group of organisms of the same species living in the same area at the same time.

- Community - multiple populations living in the same area at the same time.

Effect of abiotic factors

Since abiotic factors in a habitat are typically unchanging, organisms living in that habitat must be adapted to these abiotic factors. Two examples you are expected to remember are marram grass in dunes and mangrove trees.

Marram grass's adaptations include:

- Hairs on the underside of the leaf to reduce wind speed, and thus transpiration.

- Thin rolled leaves, creating a moist humid environment around the stomata by reducing exposure to wind. This decreases the concentration gradient, thus reducing transpiration.

- An extensive root system to reach all available water and increase water uptake.

- Thick waxy cuticle and few stomata to reduce water loss.

- Small spongy mesophyll airspaces to maintain humidity in the leaf with little water, decreasing the amount that can be lost.

The adaptations of mangrove trees include:

- Very small leaves that can shed when water is scarce, decreasing transpiration.

- Sunken stomata to enable the ability to store water in leaves.

- Long root systems to remove salt build-up and reach all available water.

- Sugar and K+ storage in the cytoplasm, as well as Na+ and Cl- in vacuoles, thus maintaining a hypertonic internal environment. This prevents the osmosis of internal water out to the saline water.

Range of tolerance

However, species are never perfectly adapted and can only survive some variation in that habitat, called its range of tolerance. This impacts the region of the habitat that the animal will inhabit and changes with genetics, age, and health status. The wider an organism's range of tolerance, the greater their ability to survive and thrive, and thus the greater their distribution. A habitat distribution will clearly demarcate the tolerance of an organism:

- At the optimum tolerance range, the conditions are perfect for the organism to thrive and they are most abundant here.

- When there greater variation in the conditions, organisms enter the stress zone, where there mental and physical health takes a toll. Thus, less organisms will be found here.

- At the extremes, the zones of intolerance begin. No organisms exist here because the conditions are too hostile for the organism to survive at all.

However, most organisms tend to have a narrow optimum range wherein function best. This varies from organism to organism, species to species, and may vary during development or seasonally.

The range of tolerance is thus a limiting factor for a species's existence in a habitat. You must be able to measure the range of tolerance using a transect, which is a line positioned to span a community of organisms. Transect sampling provides information about a species distribution along an environmental gradient such as across a seashore, or up a mountains slope. There are three main types of transect:

Point sampling on a line - in this transect, sample points are evenly distributed along a line transect. At each sample point, the abundance of an organism is measured to determine its habitat distribution.

Continuous belt - in this transect, there are infinite sample points along a belt transect (also has width), and thus the abundance of an organism is measured across the whole belt.

Interrupted belt - in this transect, the belt transect is divided into evenly distributed zones across the length and into quadrants across the width. In each quadrant, the abundance of an organism is measured.

Using transects, an organism's distribution can be estimated.

Sail through the IB!

B4.2: Ecological niches

Niches

You have now learned about organism evolution and speciation, biodiversity, and habitat. However, each habitat has a great number of species that each contribute differently. The functional role of an organism, in its environment, is its niche. There are two types of niches you need to be aware of:

- Ecological niche - the species habitat and all its interactions. This includes what it consumes, its interdependence with other species, the time of day it's active, where it lives, and where it feeds.

- Fundamental niche - the full range of conditions under which species can survive and successfully reproduce.

Note that two species with the same niche cannot coexist as they would compete with one another, leading to the exclusion of one. This topic will focus on the distribution of organisms primarily on their:

- Requirement of oxygen

- Nutrition methods

- Adaptations to nutrition

- Competition

Oxygen requirements

In the discussion of oxygen requirements, you are required to be familiar with three types of organisms: obligate anaerobes, facultative anaerobes, and obligate anaerobes. The existence of each in a habitat is highly dependent on the presence of oxygen.

While this is the case for many organisms today, Earth did not always host an atmosphere with free oxygen. The first billion years of our planet’s life did not have freely available oxygen, and it was not until 2.5 billion years ago that oxygen was produced by photosynthetic microorganisms splitting water. Thus, obligate anaerobes, facultative anaerobes, and obligate anaerobes evolved with different requirements:

- Obligate anaerobes can be found in extreme environments found on earth, such as in deep oceans, deep mud, near active volcanoes or any where that limited oxygen exists.

- Facultative anaerobes rely on sulphates, nitrates, and carbon monoxide as the final electron acceptor in respiration.

- Obligate aerobes rely on oxygen, and are thus found where obligate anaerobes and facultative anaerobes are not.

Modes of nutrition

The main modes of nutrition exhibited by organisms include:

- Autotrophic nutrition - nutrition reliant on chemical energy or light energy, such as photosynthesis. Green plants, bacteria, cyanobacteria, algae, and some archaea are all photoautotrophs.

- Heterotrophic nutrition - nutrition reliant on the ingestion of other organisms or biological material. All animals are heterotrophs but can exhibit holozoic or saprotrophic nutrition.

- Holozoic nutrition - involves the ingestion, internal digestion, absorption, and assimilation of nutrients, exhibited by most animals. This is often broken down into carnivory, herbivory, and omnivory.

- Saprotrophic nutrition - involves the ingestion of dead organic material via external or internal digestion, exhibited by fungi and bacteria.

- Mixotrophic nutrition - organisms with this nutrition mode can obtain nutrients autotrophically or heterotrophically. Euglena is a freshwater protist that exhibits this behavior.

You must also be aware that archaea bacteria shows a great variation of metabolic activity within their domain. They have:

- Phototrophic archaea

- Chemotrophic archaea

- Heterotrophic archaea

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C4.1: Populations & communities

Populations

After successful competition, a species can establish their niche in a habitat and begin a population. Remember that this is an interacting group of organisms of the same species living in an area. You are expected to understand how a population in a habitat behaves in response to external pressures.

For this to be possible, population numbers need to be monitored. A population can be monitored and aspects of it measured to provide information about that population. Population composition, population dynamics and population distribution and abundance are all such attributes that can be studied.

This is mainly performed by random sampling, which is useful to provide insight of the population dynamics. Such insights may reveal information about the composition, distribution, density or more of that population. It is often neither feasible nor practical to count all members of a population as there are often too many individuals and time is not infinite. Thus, sampling is a means of circumnavigating these setbacks to get a good insight about the population in question. Precisely how well the sample represents the population, is a question of understanding the significance of the extent of error.

Sampling can provide information about:

- Population size - how many members of that population reside in a specific area. Counting some individuals in a stated area and extrapolating to approximate the entire population size is a way to estimate this.

- Population distribution - how a given population is distributed, and whether it is stable or fluctuates. This is useful when investigating the geographical range of species.

- Age distribution - the abundance of different age groups, including infants, adults, and elderly organisms. This can be used to determine breeding programs for endangered species for example.

Note that estimating population size is not without challenges. Populations may be unevenly distributed over vast areas, they may be mobile, they may be hidden; In any given area there may be fewer or more individuals than in any other area. Population statistics must take this into account when estimating population size. It is assumed that any such estimate will come with a margin of error as not all the population has been measured.

For this reason, sample statistics will always be somewhat of a departure from any precise population parameters. The difference between these values is the sampling error. However, as we rarely know the actual population parameters, the sampling error is estimated using a confidence interval.

Methods of estimating population size

While random sampling will hold true for any estimation protocol, different organisms are present in different numbers and move around differently, requiring different estimation methods. The two main methods you need to be aware of are:

- Random quadrat sampling - mainly used for sessile species. During this, a series of random placements of a quadrat frame of known dimensions, across an area, are used to estimate the abundance or diversity of organisms. Quadrat sampling can also be used to test for the association between two species. For this:

- Enter the observed values (O) into the contingency table.

- Calculate the expected value (E) and enter into the contingency table.

Calculate (O-E) and use it to find the value of chi squared (χ2):

χ2=ΣE(O−E)2

- Use the χ2 table to determine the critical χ2 value. For this, the degrees of freedom are always 1, and the significance α is typically 0.05, unless specified otherwise.

Capture-mark-release - mainly used for motile species. A sample of animals is first randomly captured, marked, and released back into the wild. After a period of time, a second capture occurs, which may capture previously caught organisms. Population size can be determined using the Lincoln index.

N=RMS

Here, N is the population size estimate, M is the marked individuals released, S is the second capture size, and R is the number of marked animals recaptured.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C4.2: Energy & matter transfer

Ecosystems

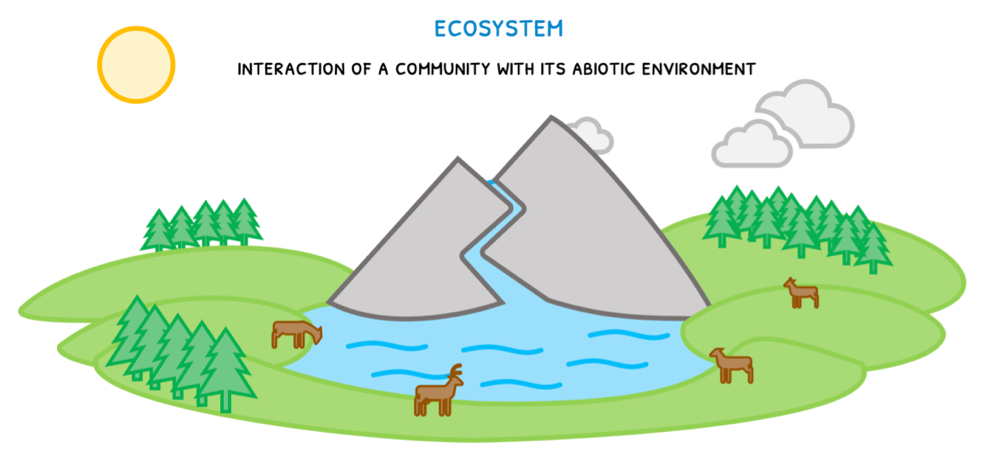

A huge focus on Topic 4 is ecology, defined as the study of ecosystems, and you are expected to know them in detail. An ecosystem is the interaction of a community with its abiotic environment. Within this:

- The nutrient supply is maintained via cycles, making it extremely sustainable.

- The energy supply is not maintained, as energy is able to pass in as sunlight and pass out as heat.

By definition, this makes ecosystem closed systems, as energy is able to move in or out, but matter is not (for the most part). Remember that sunlight is the principal source of energy that sustains each ecosystem on the planet, with exception of:

- Caves - deep enough, sunlight is unable to reach and provide energy for the ecosystem. Energy thus enters in the form of entering animals or debris that has washed in.

- Deep water - deep enough, sunlight does not penetrate either and thus it does not provide energy. Energy thus enters in the form of dead animals that have sunk into the deep ocean.

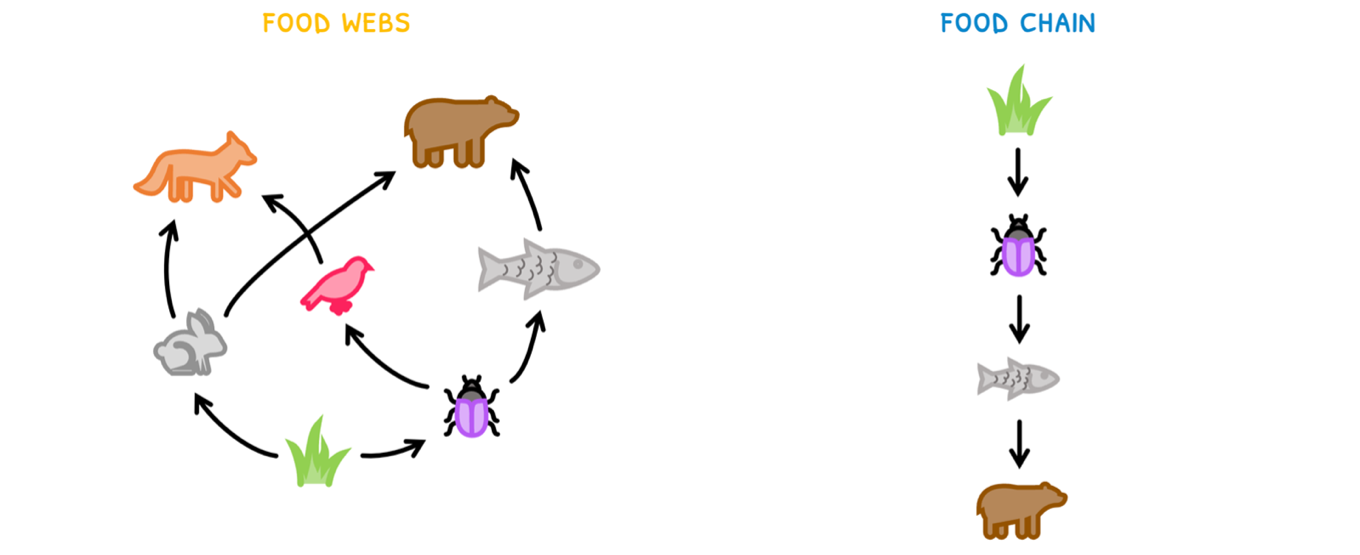

Food networks

Within each ecosystem, all organisms that live within it need energy. Thus, energy needs to flow through complex feeding networks, which can be represented using food webs.

Each individual route within a food web is called a food chain, so you can see that a food web is composed of many food chains.

Modes of nutrition

In these food webs, species can be divided into three types based on their mode of nutrition: autotrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic.

- Autotrophs obtain energy by converting inorganic compounds into organic compounds via photosynthesis. Examples include plants, algae, and cyanobacteria.

- Heterotrophs obtain energy by consuming other organisms. There three types:

- Consumers - these directly consume other living organisms and perform internal digestion and absorption of their compounds.

- Detritivores - these directly consume decomposing matter or organisms and perform internal digestion and absorption of their compounds.

- Saprotrophs - these secrete digestive enzymes onto dead organic matter for external digestion, and then absorb the products.

- Mixotrophs are both autotrophs and heterotrophs. An example is a Venus fly trap.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D4.1: Natural selection

Natural selection

Previously, the concept of evolution and evidence supporting the theory was covered. This topic focuses on the process of evolution via natural selection.

Natural selection is the process by which an organism that is more adapted to its environment can survive, and so pass on the genes for its adaptation to its offspring. In order for this to occur, two criteria must be met:

- There must be genetic variation within the population that causes different characteristics. These are caused by:

- Mutation - to form new alleles.

- Meiosis - to form new combinations of alleles via crossing over in prophase I or random orientation in prophase II.

- Sexual reproduction - combining alleles from two individuals to form groups of alleles.

- This variation must result in an adaptation. This is defined as a characteristic that make an organism suited to a particular way of life.

Having genetic variation bring about an adaptation in a portion of the population then allows for natural selection to occur:

- At some point, populations will experience overpopulation, increased predation, a loss in habitat, or a loss of resources.

- This will create competition for survival within a population.

- The organisms more adapted to the environment are therefore more likely to survive, and those that are not are more likely to die.

- The organisms that survive can then reproduce and create offspring, whereas those that survive do not.

- The genes for their adaptation is then inherited by these offspring.

- Therefore, over time, there is an increase in the proportion of adapted organisms.

As this is a change in heritable characteristics over time, it is evolution, but it occurs via selection of particular traits due to natural pressures on the population.

Sail through the IB!

D4.1: Further natural selection (HL)

Patterns in natural selection

In the HL syllabus, you need to know more detail about natural selection. Here, you are supposed to appreciate that many characteristics are polygenic and thus impact an organism's ability to survive and reproduce. In the context of natural selection, the term used for all these characteristics is gene pool. This is all the genes, and their different alleles, present in an interbreeding population.

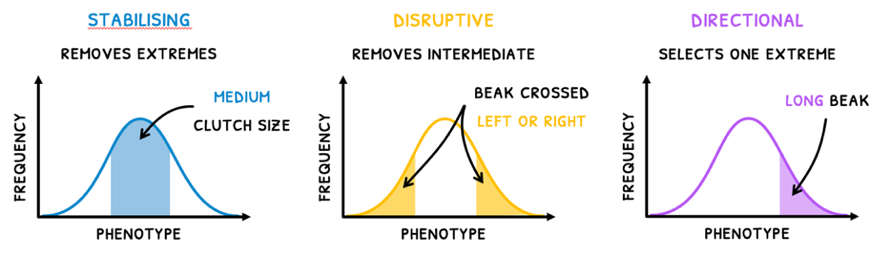

Due to natural selection, some alleles may appear more frequently than others. This can be visualized by gene pool distribution, and there are three main patterns you need to be aware of:

Stabilizing natural selection - this occurs when selection pressures remove the extremes of a phenotype.

For example, the clutch size of eggs are mostly medium in number, as too few eggs decreases survival rate, whereas too many increases predation.

Disruptive natural selection - this occurs when selection pressures remove the intermediate phenotype.

For example, the beak of the red crossbill is either crossed left or right, but never straight as the crossing allows it to extract conifer cones and obtain food.

- Directional natural selection - this occurs when selection pressures select one extreme of a phenotype. For example, the Darwinian finches during El Nino were selected for longer beaks during times of drought.

Genetic equilibrium

The impact of natural selection is important, because generation upon generation it changes the population's gene pool by weeding out characteristics that are less well adapted. In periods of stagnation, all members have an equal change of reproducing and thus the population is said to have reached a state of genetic equilibrium.

Remember that long periods of no appreciable change like this support punctuated equilibrium, whereas gradual changes over time support gradualism.

Sail through the IB!

D4.2: Stability & change

Ecosystem stability

Ecosystem stability is the ability of an ecosystem to maintain its structure and function over long periods of time and despite disturbances. It is a natural property of an ecosystem that is the product of multiple factors since ecosystems are dynamic and subject to constant change.

Whilst some factors are cyclical, such as seasons, others longer, ecosystems tend to remain stable over extremely long-time frames. The key requirements for ecosystem stability are:

- Sufficient genetic diversity

- Sufficient energy supplies

- Nutrient recycling

- Climatic variables within tolerance levels

However, any shift in biotic or abiotic factors can bring diversion from the seasonal norms. Natural cycles, natural disasters, and human activity are all capable of altering ecosystem stability.

If an ecosystem reaches a tipping point, defined as a point of no return, the feedback mechanisms that maintain ecosystem stability are irreversibly damaged and cause rapid change within that ecosystem.

A key example you need to be aware is deforestation of the Amazon rain forest. Scientists predict that if deforestation in the Amazon reaches 20-25% a tipping point will be reached. This is of great concern as it already stands at 17% deforestation. Of further global concern is the loss of biodiversity that accompanies deforestation since species biodiversity is highest in the tropics, and habitat loss puts many species at risk of becoming endangered or even extinct.

The reasons for deforestation are largely socioeconomic, and in tropical regions subsistence farming is a major culprit. The clearing of land for commercial agriculture, to include ranching and palm oil plantations, results in revenue for governments through taxes and permits. This becomes an incentive to clear more forests. Some 14% of Amazon deforestation is also attributed to logging, although illegal logging may also push this percentage up even higher.

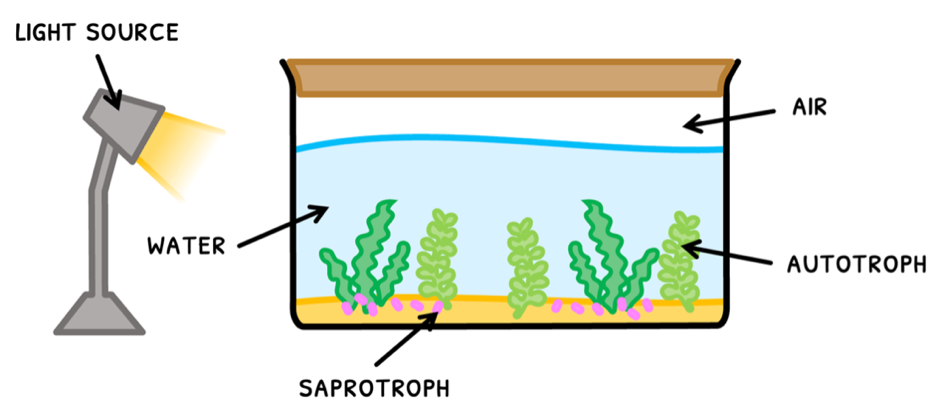

Mesocosms are able to model an ecosystem's sustainability as artificial miniature versions of them. Their main use is in the investigation of how different factors affect that sustainability. From these experiments, it became evident that to maintain themselves, mesocosms must contain:

- A light source to initiate photosynthesis as the entry point of the energy cycle.

- Air to provide oxygen and other gases needed for life.

- Water needed for life.

- An autotroph to perform photosynthesis and take up nutrients and minerals from the soil.

- A saprotroph or detritivore to decompose waste material and dead organisms, returning nutrient and minerals to the ground and essential gases to the air.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D4.2: Ecological stability (HL)

Succession

In the maintenance of ecosystem stability, you have learned about the important factors, sustainable practices, pollution, and restoration. However, sometimes ecosystem destruction (such as in natural wildfires) is beneficial for the restart of an ecosystem. During this restart, the ecosystem has to be rebuilt over time via ecological succession.

Ecological succession refers to the process of sequential change over time in an ecosystem. Usually, it comes about in response to a disturbance and is the result of the interactions (dynamic) between biotic and abiotic conditions. Earlier communities modify the environment, making it more favourable for the future species in the communities that will come next. In time succession may result in stable, mature or climax communities. Succession that occurs where there is no soil is called primary succession.

Primary succession

Primary succession occurs when new land is formed or exposed for the first time.

This could be the result of cooling lava creating new rock, or when a glacier retreats, exposing rocks that have no soil on them. It can also happen if a previous community has somehow been extinguished.

During primary succession there are multiple changes in the composition of the communities that develop over time. Each stage in succession is referred to as a sere or a seral community. The early seres have a simple structure and a lower species diversity than the later stages. They will host the smaller plants capable only of low primary production, limited nutrient cycling and very simple food webs. Over time the developing community modifies the abiotic environment. The process is as follows:

- The earliest pioneer species are microorganisms, such as cyanobacteria. They can survive the substrate free environment thanks to their autotrophic ability, using only sunlight to make food.

- Lichens begin the process of forming soil by breaking down substrate, and adding organic matter to it when they die and decay. Their presence, life and death therefore create a favorable environment for vascular plant growth.

- Then, the community evolves to house intermediate species. These are typically larger and denser plants such as shrubs and pine trees. There is now increased primary productivity, and this leads to stable nutrient recycling and more complex food webs than in the former seres.

- Eventually, the climax community is formed with the arrival of shade tolerant trees such as oak and hickory. Climax communities in a state of stable equilibrium and are deemed to be the final or end stage of succession.

Ecosystems then undergo one of two pathways: cyclical succession or arrested succession.

Cyclical succession

Some ecosystems are subject to cyclical change. This is because some communities are subject to constant changes and so experience cyclical succession. The removal or appearance of species that happens due to natural cycles such as fires or changes in lifestyle stages in animals, causes repeated succession to a climax community.

Cyclical succession can be triggered by events that reoccur, such as the death of old trees, or by wildfires that change the composition of a community, and this can happen in repeated cycles. It can vary in its length depending on the community in question.

For example, the chaparral ecosystem on the California coast is subject to natural wildfires that occur every 30-150 years. Each time this happens a succession of different plant species replace one another, in the same order.

Sail through the IB!

D4.3: Climate changes

Climate change

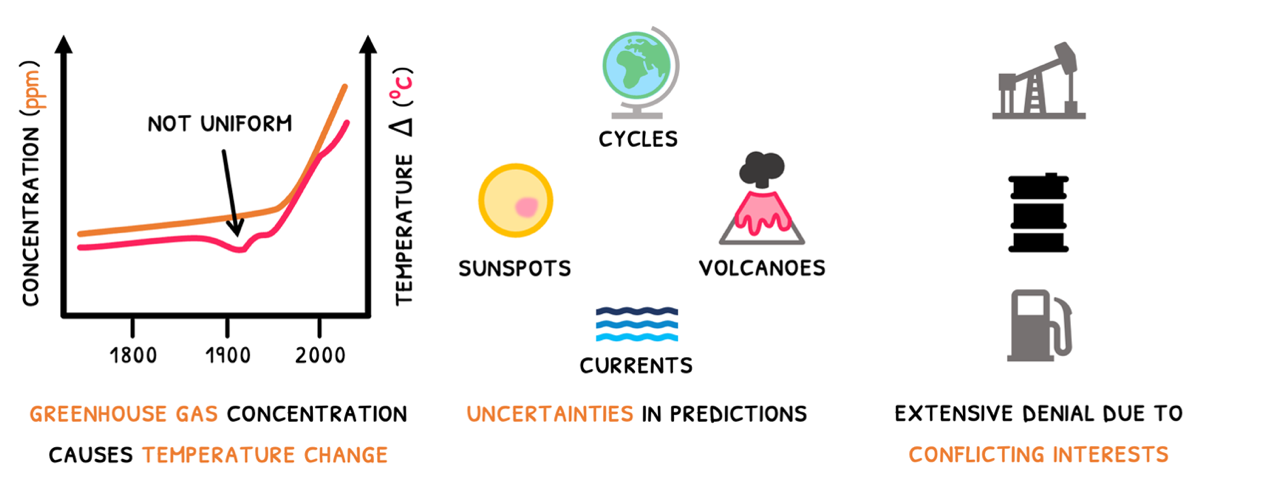

You are likely familiar with climate change as a concept, and need to know more about it in this topic. It is defined as an extreme change in climate conditions due to changing global conditions. This disruption to our climate is commonly attributed to human activity. However, there is still opposition to this so let's review the evidence for and against climate change.

- Drilling into ice from thousands of years definitively shows a strong association between atmospheric carbon dioxide and global temperature.

- Natural processes such as Milankovitch cycle, sunspot activity, ocean currents, and volcanoes all contribute to the climate.

- Carbon dioxide has naturally fluctuated throughout history due to shifting tectonic and volcanic activity.

- Additionally, global warming does not increase uniformly whereas carbon dioxide concentration does.

- However, carbon dioxide concentration has drastically increased since the 1950s at a historic rate.

- This coincides with the additional mass burning of fossil fuels by humans, and the associated increase in temperature.

There is extensive denial on this evidence due to conflicting interests, especially from companies that profit from fossil fuels. However, all the evidence has been analysed by many climate change scientists, who have almost unanimously concluded that climate change is an anthropogenic process.

Global warming

Evidence shows that climate change is a direct result of global warming due to the enhanced greenhouse effect. Due to continuous carbon emissions and the positive feedback of the greenhouse effect on global warming, this unfortunately creates more positive feedback loops that have led to the increase in both CH4 and CO2 gases in the atmosphere. You are expected to understand how the different positive lead to this:

- The albedo effect - sea ice has a high reflectivity or ‘albedo’ and this helps maintain cold temperatures. However, climate change has caused sea ice to retreat, exposing non-reflective surfaces. Heat is absorbed not reflected and this further warm both the air and sea. Symptomatic of these events, there is currently less and thinner sea ice.

- Water vapor release - climate change has led to warmer temperatures, in turn leading to higher rates of evaporation from surface waters. This increases the amount of atmospheric water vapor, contributing to the greenhouse effect, trapping heat energy in the atmosphere, culminating in erratic weather events.

- Release of CO2 from deep oceans - dead microorganisms on the ocean floor sediments transport carbon. Stored as CO2 in freezing conditions and under pressure, warming oceans release the formerly stable stored CO2 into the ocean, and it is eventually released from the water surface to the atmosphere, contributing to the greenhouse effect.

- Release of methane from permafrost - large quantities of methane are stored underground in the polar regions and also under the ocean as clathrates. Global warming is causing the permafrost to thaw out, causing methanogenesis, releasing methane to the atmosphere. Thawing clathrates directly release methane gas.

- Increases in droughts and forest fires - the increased temperatures apparent in climate change are causing droughts. Such conditions cause vegetation and dead material on forest floors to dry out and increase the risk of forest fires. Wildfires themselves involve the combustion of plant material and the release of large quantities of CO2 into the atmosphere. If such fires are located near ice or snow, the soot and smoke released can reduce the albedo.

Thus, each of these events exemplify positive feedback loops that drive climate change by increasing greenhouse gas emissions, driving further global warming, and further exacerbation of these same issues.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D4.3: Further climate change (HL)

Phenology

Phenology is the study of seasonal changes in plants and animals and how they are influenced by seasonal cues. Many biological phenomena synchronise with day length (photoperiodism) or temperature change, such as:

- Bud burst

- Bud set

- Flowering

- Dormancy

These events must align with other biotic and abiotic ecosystem occurrences to coincide with seasonal light and warmth for growth, pollination and seed dispersal. Additionally, the migration of animals and birds and bird nesting must also be carefully timed to coincide with availability of resources.

However, the timing of biological events is being changed due to global warming. As such timings are often interlinked between species, disruption to one species will influence another.

If for example, growth or budding of a particular species needs to occur at a specific time, when a particular breeding animal species relies on that food source, such disruption will impact that. Timed events can become unsynchronised when warmer temperatures bring one set of events in one species forward, but a second species uses photoperiods uninfluenced by climate change.

There are three particular examples to remember:

- The great tit - this is a bird that feeds on caterpillars, a great energy source needed to raise their chicks. Climate change has pushed peak caterpillar growth and populations forward, mismatching the peak caterpillar supply as a food source for great tits and chick hatching. As a result, a higher rate of unsuccessful breeding is occurring, decreasing the population of the great tit. Models predict that a 24-day mismatch between peak caterpillar supply and chick hatching could lead to local extinction of the great tit.

- In the northern tundra, reindeers migrate in late spring to their feeding grounds. Here they feed on herbs and local vegetation. The cue for this is day length and so this is consistent from year to year. However, their main food source, Arctic mouse-ear chickweed is temperature sensitive and thus when it becomes too warm, it dies and no longer appears when the reindeer arrives, creating a mismatch.

- Spruce bark beetles have life cycles that span two years. They lay eggs in the tree bark in June. These hatch as larvae and within a month they start consuming the spruce. Soon after they pupate and re-emerge the following spring as adults. The cue for their emergence is an ambient temperature of 16°C. When summers are warmer, spruce bark beetles compress their life cycle from 2 years to 1 year. Ultimately climate change is increasing the damage done by such insects. The shortened life cycles of the beetles mean more beetles are reproducing, increasing population numbers. Normal predator–prey systems which afford the trees time to regenerate in between population bursts are being disrupted.