IB Chemistry Topic 2 & 12 Notes

S2.1: Ionic bonds & structure

Introduction to Bonding

In this topic, you will explore the types of bonds within molecules, called intramolecular bonds (aka. interatomic bonds), and the bonds between molecules, called intermolecular bonds (aka. intermolecular forces).

There are three intramolecular bond types you need to be aware of. These are shown below in order of decreasing strength:

- Covalent bonding (strongest)

- Ionic bonding

- Metallic bonding (weakest)

When considering covalent compounds (formed from covalent intramolecular bonds), there are also three intermolecular bonds/forces you need to be aware of. These are shown below in order of decreasing strength:

- Hydrogen bonds (strongest)

- Dipole-dipole forces

- London dispersion forces (weakest)

You may have heard ionic bonds are stronger than covalent, and whilst there are certain situations in which this can be the case, it depends on the environment in which the ionic species is found (solvated, vacuum, etc.) and the IB does not recognise this. Therefore, for your IB exam you should focus on the intramolecular ranking listed above.

Ionic bonding

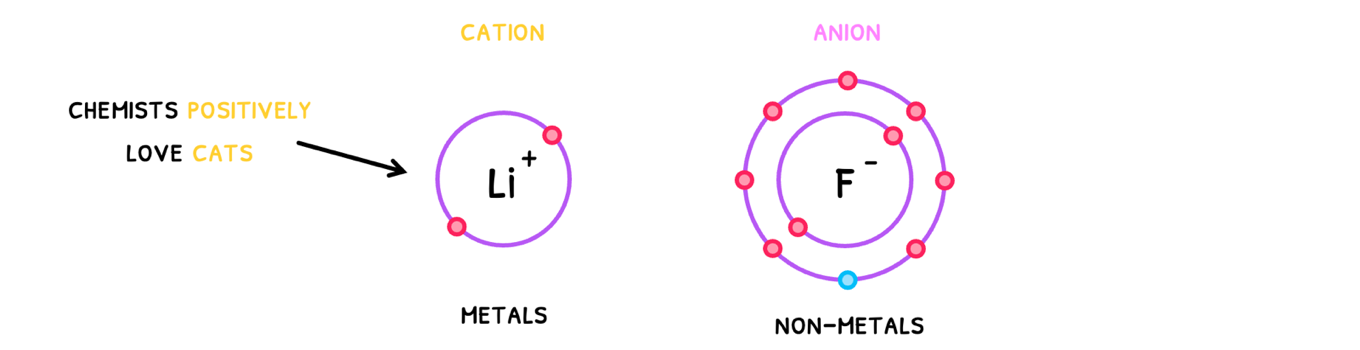

An ionic bond is the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions. Remember that ions are formed when atoms lose or gain electrons to become cations or anions.

- Cations - ions with a positive charge.

- Anions - ions with a negative charge.

To remember which is which, use the phrase "Chemists positively love cats".

Note that cations are typically metals and anions are typically non-metals. Thus, to know if they have an ionic bond, look at the electronegativity difference of the elements. If it is greater than 1.8, they form an ionic bond!

Additionally, note that when atoms become ions, they become isoelectric with another atom or ion. This means that they have the same electron configuration!

Ionic Compounds and Properties

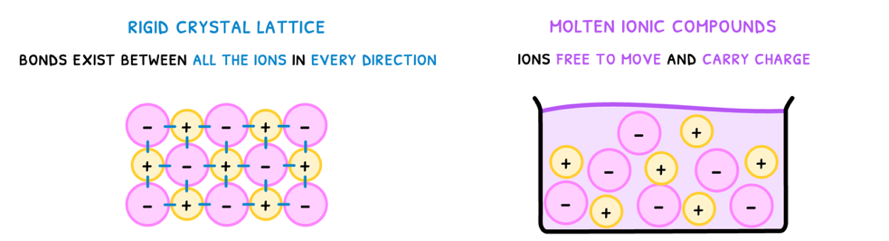

Next, you need to understand the structure that is formed when many ionic bonds come together as an ionic compound. However, the structure depends on the state of the compound:

- Solid - forms a rigid crystal lattice as bonds exist between all ions in every direction.

- Liquid - no lattice as ions are free to move.

Knowing the structure of ionic compounds, you can understand their properties:

- High melting and boiling point - due to the strong electrostatic attraction between the ions in their respective lattices, ionic compounds require large inputs of energy to break apart these forces.

- Volatility - this refers to the ease at which a substance vaporizes. Due to the strong electrostatic attraction, ionic compounds have very low volatility.

- Solubility - ionic compounds dissolve in polar solvents but not in non-polar solvents. Only solvents which contain molecules with partial charges can dissolve ionic compounds. These partial charges can pull individual ions from the lattice.

- Conductivity - ionic compounds cannot conduct electricity in the solid state as the ions are fixed in place. However, when molten, the ions can move around freely and thus conduct electricity.

S2.2: Covalent bonding & forces

Covalent Bonds

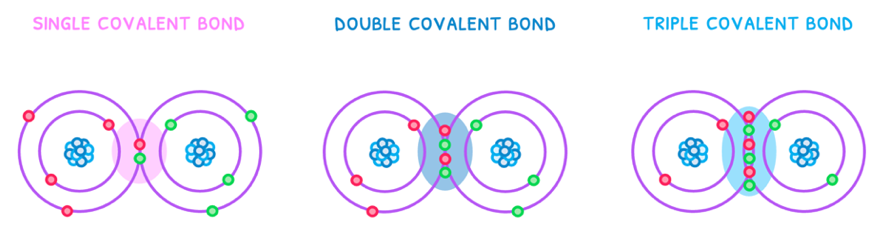

The next intramolecular bond to learn is the covalent bond. This is defined as the electrostatic attraction between a pair of nuclei and their shared pair of electrons. This is the strongest type of intramolecular bond and typically occurs between non-metals.

During a single covalent bond, two electron orbitals with one electron each overlap so that the electrons are paired in what is known as a molecular orbital. The remaining pairs of electrons are left in the valence shell of the atoms involved and become known as “lone pairs”.

There are three types of covalent bonds:

- Single - one pair of electrons is shared. This is therefore the weakest and longest bond.

- Double - two pairs of electrons are shared. This is therefore the bond of intermediate strength and length.

- Triple - three pairs of electrons are shared. This is therefore the strongest and shortest bond.

This is summarized in the table below:

| Bond type | Bond strength | Bond length |

|---|---|---|

| single | weakest | longest |

| double | intermediate | intermediate |

| triple | strongest | shortest |

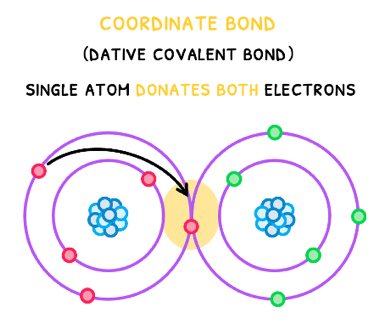

Coordinate Covalent Bonds

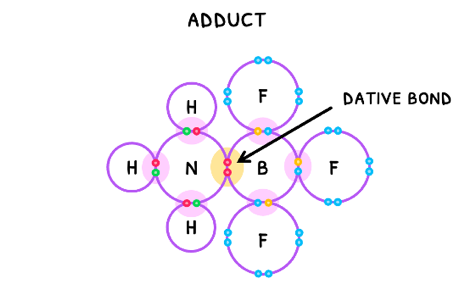

Whilst the pair of electrons contained within a covalent bond generally come one from each atom, this is not always the case. In a coordinate bond, also called a dative covalent bond, a single atom donates both electrons. Once this bond forms, it is identical to a regular covalent bond, the only difference is the origin of the electron pair.

When a coordinate covalent bonds occurs between two molecules, this forms an adduct.

An example is NH3 and BF3. Here, the the Nitrogen atom within NH3 donates a lone pair to BF3, forming a dative bond.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

S2.2: Further covalent bonding (HL)

Higher Level Covalent Bonding

In the HL syllabus of Topic S2.2, you need to understand several more components of covalent bonding, including:

- Two additional VSEPR domain geometries

- Using formal charge for Lewis structures

- Electron sharing in bonds

- Hybridization

VSEPR Theory

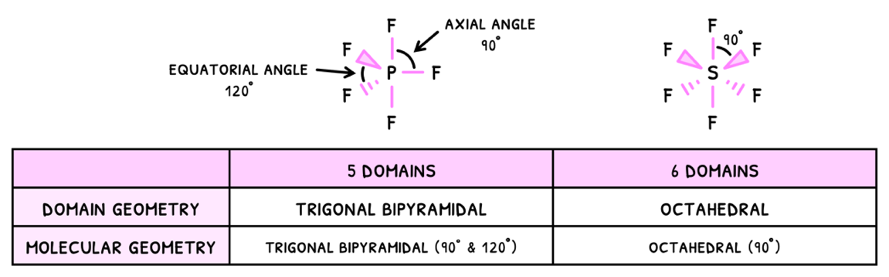

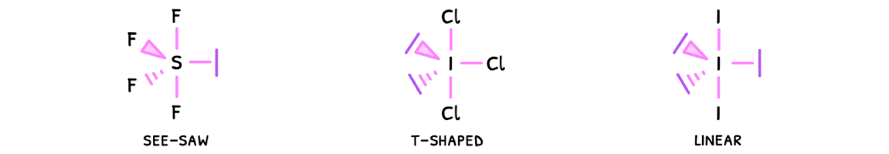

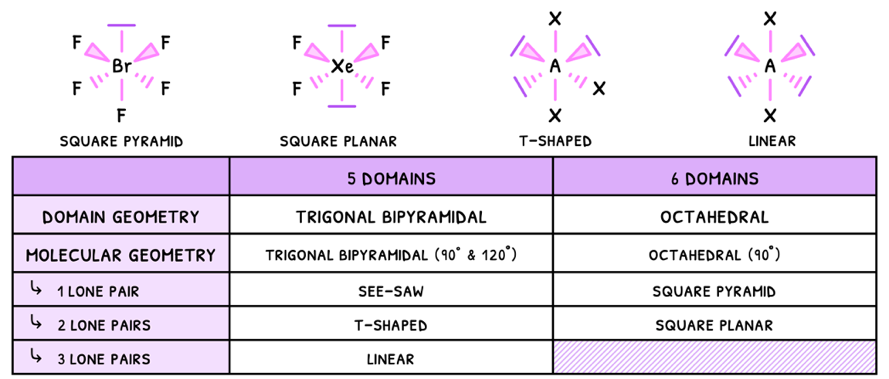

Starting with VSEPR, you need to know the additional two domains:

- Trigonal bipyramidal - 5 electron domains

- Octahedral - 6 electron domains

Just as before, the presence of a lone pair will decrease the bond angles by 2.5°, and this effect compounds. However, in some cases the pairs cancel one another and so the bond angles do not decrease.

- Linear - electrons are removed from the equatorial plane, so the angle here becomes 180°.

- Square planar - electrons are removed from the axial plane, so the angles become 90°.

Formal Charge

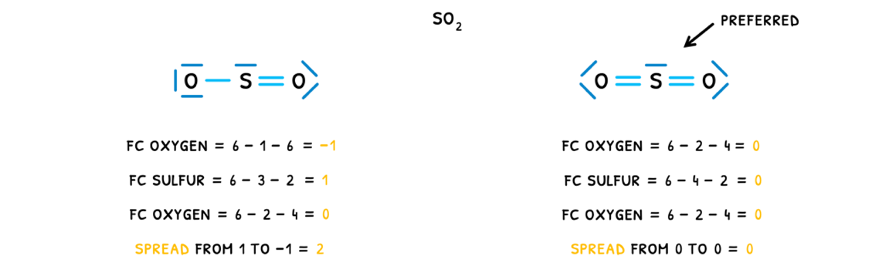

Next, you need to know more details about resonance structures. This is because when drawing Lewis structures, you will trouble finding the correct one when resonance structures exist. However, the concept of formal charge is incredibly useful to confirm you have chosen the correct Lewis structure.

Formal charge is used to decide between different Lewis structures because the Lewis structure with the smallest formal charge is preferred. To do this:

- Calculate formal charge for each atom in the compound. The formula for this is:

valence electrons−21bonding electrons−non bonding electrons

- Summate all the formal charges.

Performing this for two possible Lewis structures of SO2, the preferred structure can be found:

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

S2.3: Metallic bonds

Metallic Bonds

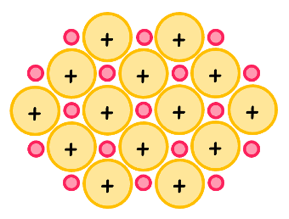

This topic focuses on the last intramolecular bond - the metallic bond. These are the weakest type and occur only between metals. It is defined as the electrostatic attraction between a regular lattice of positive ions and a sea of delocalized electrons.

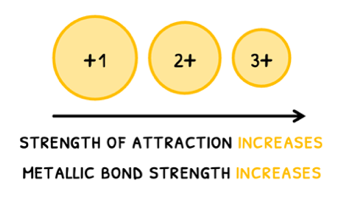

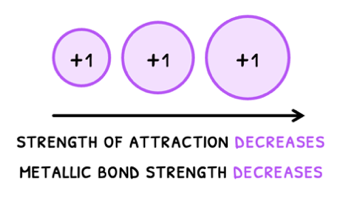

When considering metallic substances, there are two factors that affect the strength of the metallic bond:

- Ionic charge - as charge increases, the strength of the attraction between the positive ions and delocalized electrons increases. Therefore, metallic bond strength increases and melting and boiling point increase.

- Ionic radius - as ionic radius increases, the attraction decreases as the nucleus of the positive ion is further from the delocalized electrons. Therefore, metallic bond strength decreases and melting and boiling point decrease.

It is important to note that charge has a greater effect on attraction than size!

Interestingly, this association between bond strength and melting point only applies up to Period 3, after which atomic arrangement starts to affect melting point as well. For instance, Mercury is liquid at room temperature!

Properties of Metals

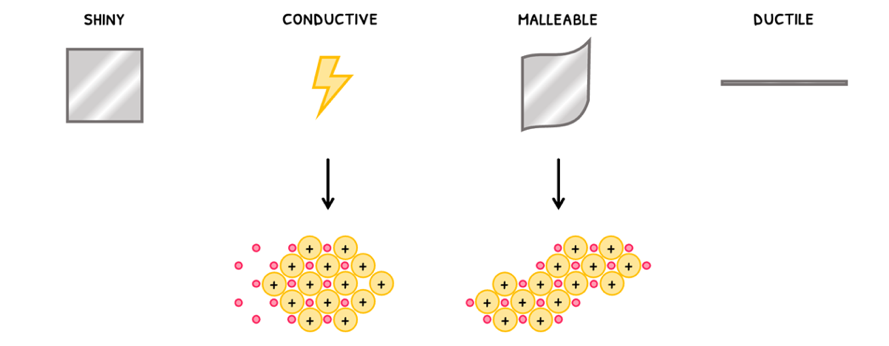

However, in general all metals have similar properties:

- They are shiny.

- They are conductive. Remember this is because the sea of electrons can move and carry charge.

- They are malleable. Since electrons attract the positive ions in all directions, the layers can slide over one another.

- Finally, metals are ductile, meaning they can be stretched out and made into a wire.

S2.3: Further metallic bonding (HL)

Transition metals

So far in the syllabus, transition metals have only been mentioned briefly and you need to know more about them for your HL syllabus.

By definition, transition metals are metals that have, or form, partially filled d-orbitals. Since these electrons are present in the outer shell, they are easily lost and participate in metallic bonding.

Thus, 3d transition metals have 3d electrons and 4s electrons in their metallic structure. The general trend is that when more electrons are involved, the stronger the bond becomes. This causes the main physical properties of transition metals:

- Higher melting and boiling points than other metals.

- Higher conductivity than other metals.

The periodic trend for melting point however is not evident. It should be the case that across the period of transition metals, melting and boiling point increase as more electrons are added. While this is generally true, there are exceptions to this rule so let's review these:

- Across a period, nuclear charge increases.

- Shielding effect does not increase.

- Thus, effective nuclear charge increases across a period.

- This, combined with the increased number of delocalized valence electrons should result in a stronger metallic bond.

However, since there are a significant number of electrons in the valence shell now, there is considerable electron repulsion across the period. This results in the decrease in melting point seen in Vanadium and Cobalt to Copper.

The sudden drops in Manganese and Zinc can be explained by the half full and full d-orbital, which is so stable that these electrons do not participate in metallic bonding.

Additionally, remember that Chromium and Copper sacrifice a 4s electron to create a half-full or full d-orbital. This thus also significantly decreases melting point, but the remaining 4s electron can participate in metallic bonding.

S2.4: Models to materials

Bonding Triangles

Classifying bonding as either ionic, covalent, or metallic can be limiting and does not allow us to classify compounds by their specific properties when they do not fit perfectly within a category.

Many materials are composite e.g carbon fibre or concrete, meaning that they are mixtures of two different compounds in different phases and the individual compounds retain their own properties. The understanding of the mixture of properties is necessary for the identification of materials for specific purposes.

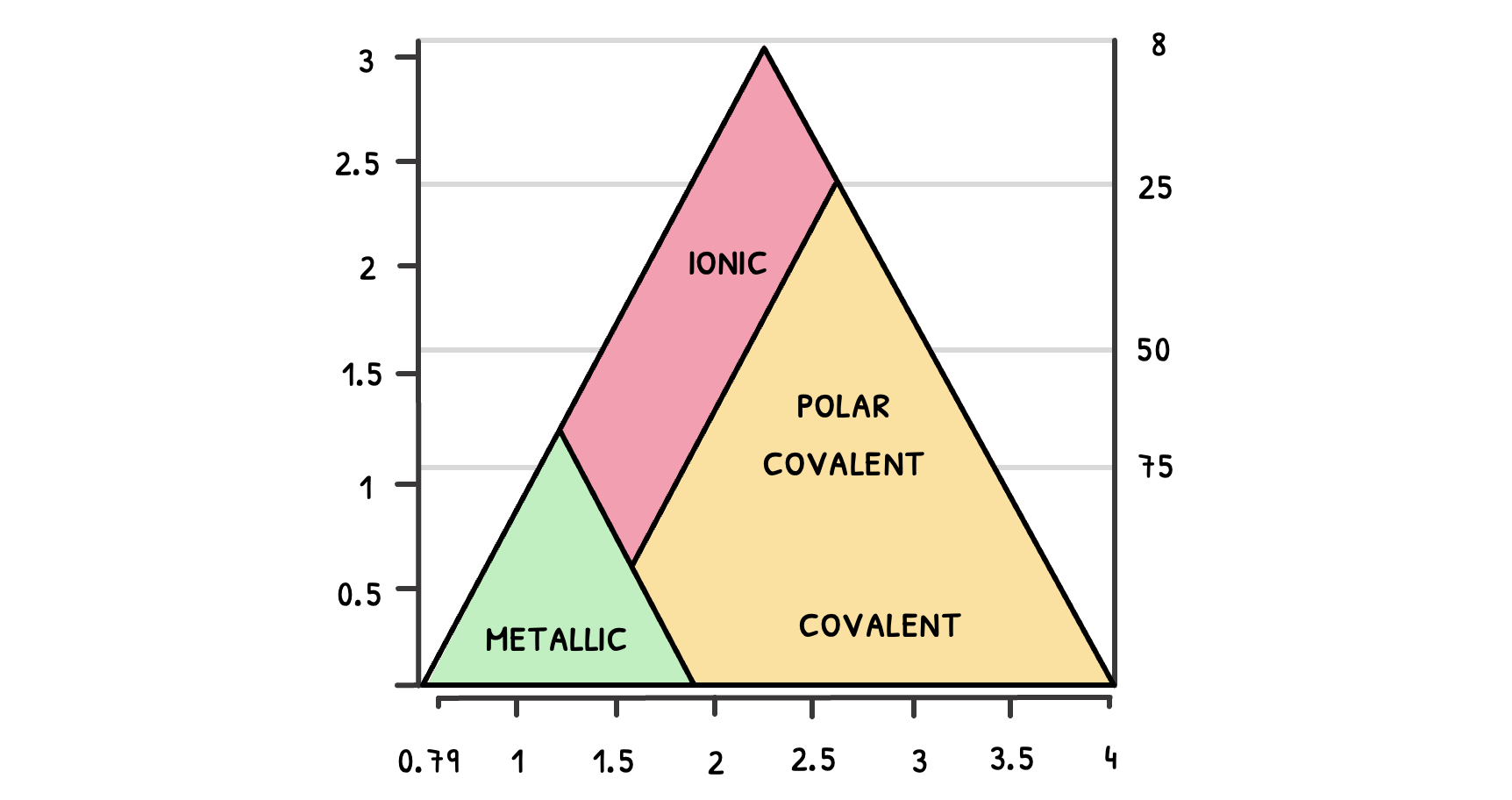

The bonding triangle, sometimes called the Arkel-Ketelaar triangle, represents bonding as a continuum and illustrates differences between ionic, covalent, or metallic bonding as well as everything in between. It is useful to reiterate that usually, compounds with a higher electronegativity difference have a more ionic character and compounds with a low electronegativity difference have a covalent character.

The bonding triangle is split into fields being metallic, ionic, covalent or polar covalent, and is set up with a y and x-axis, where the x-axis represents the average electronegativity, and the y-axis represents the difference in electronegativity. In the bonding triangle the three angles are the following bonding characteristics:

- Strongly ionic on the top

- Strongly covalent on the bottom right

- Strongly metallic on the bottom left

The most metallic atom with the lowest electronegativity is Caesium, the most electronegative atom is Fluorine and hence the most ionic molecule is Caesium fluoride, which could represent the 3 angles of the bonding triangle. The bonding triangle can be used to work out the properties of a variety of compounds. In SL you will only have to work out properties of binary compounds.

Alloys

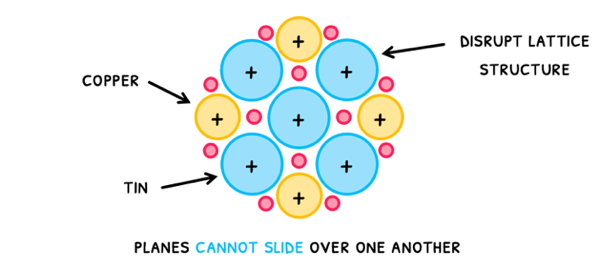

However, metals can bond with one another, completely changing their properties. When this happens, they are termed alloys.

Alloys tend to be stronger and stiffer than their individual elements, because the two elements have differently sized positive ions. This disrupts the lattice structure, preventing the planes from sliding over one another.

Common alloys include:

- Steel = Iron (Fe) + Carbon (C)

- Stainless steel = Iron (Fe) + Carbon (C) + Chromium (Cr)

- Bronze = Copper (Cu) + Tin (Sn)

- Brass = Copper (Cu) + Zinc (Zn)

- Pewter = Tin (Sn) + Antimony (Sb)

Sail through the IB!

S2.4: Condensation polymers (HL)

Biological reactions

If you take IB Biology, you will learn about metabolism. This is the complex network of interdependent and interacting chemical reactions occurring in living organisms. This typically involves the interchange between basic unit molecules, called monomers, and large polymers, called macromolecules.

To form these, chemical reactions involved in metabolism are divided into two types:

- Catabolic reactions – these are reactions that break down macromolecules into monomers. All biological monomers will be formed via a hydrolysis reaction, which uses water to split the macromolecule.

- Anabolic reactions – these are reactions that combine monomers to form macromolecules. All biological macromolecules are formed via a condensation reaction, which produces water or methanol from the monomers.

In this topic, you are expected to focus on the formation of polymers via condensation reactions.

Condensation polymerization

Since the nature of condensation reactions is to release water or methanol, it means that the monomers involved must have functional groups with oxygen and hydrogen - such as a hydroxyl, amine, or carboxylic acid group. In order to form a polymers, these groups must be present on both sides of the molecule so that the monomer can lengthen in both directions.

However, we know that polymers typically have a repeating structure. You are expected to remember two examples: polyesters and polyamides.

Polyesters are formed when a dialcohol reacts with a dicarboxylic acid, forming a water molecule for every ester link.

A common commercial polyester is polyethylene terphthalate (PET), formed from the condensation reaction between ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid. This is often threaded to be used in clothes or used as a hard plastic in water bottles.

Polyamides are formed when a diamine reacts with a dicarboxylic acid, forming a water molecule for every amide link.

This creates the common commercial polyamide called Nylon 66. This is spun into fibers for textiles, carpets, and molded parts.

Polyamides can also be formed when an amino-carboxylic acid (amino acid) reacts with itself, also forming a water molecule for every amide link.

This is performed in organisms to synthesize protein chains that then combine with other chains or fold into the final functional protein.