IB Chemistry Topic 1 Notes

S1.1: Particulate matter

Types of matter

To begin chemistry, it is important to understand that matter can appear as three types of substances: elements, compounds, and mixtures.

- Elements are the simplest substances made of atoms that cannot be broken down.

- Compounds are substances made up of two or more atoms chemically bonded in fixed ratios and have different properties than their components.

- Mixtures are substances made up of more than one element or compound not chemically bonded together so that they retain their individual properties. There are two different types of mixtures:

- Homogeneous – the components of the mixture are uniformly distributed. They thus cannot be distinguished from one another. This often occurs when two components are in the same state (such as water & alcohol), but this may not always be the case (such as water & oil).

- Heterogeneous – the components of mixture are not uniformly distributed. They thus can be distinguished from one another. This often occurs when two components are in different states (such as water & sand), but again, this may not always be the case (such as water & sugar).

In chemistry you often need to deal with pure substances, but most substances are found as mixtures in nature. You are expected to be aware of six separation techniques for mixtures: solvation, filtration, recrystallization, evaporation, distillation, and paper chromatography.

- Solvation dissolves a solid mixture in a solvent. The solvent molecules dissolve the soluble substance, leaving behind the insoluble substance. For example, salt in a mixture of sand and salt can be dissolved by adding water. This dissolves the salt and separates it from the sand, which remains undissolved.

- Filtration separates a mixture containing solids via a filter. Depending on the size of the pores, the filter allows liquids, gases, and small solid particles to pass through, but traps larger solid particles. For example, a mixture of water, sand, and rocks can be separated using a paper filter to filter through the water, and a small pore strainer to filter through the sand, leaving the rocks behind.

- Recrystallization splits a solid mixture by solubility at different temperatures. The mixture is dissolved in a hot solvent, and the solution slowly cooled. As the solution cools, the less soluble solids crystallize first and can be physically removed. For example, in a mixture of salt, sugar, and hot water, sugar is more soluble than salt. Thus, as the solution cools back down, the salt will recrystallize first, allowing for it to be filtered out of the solution.

- Evaporation removes a solvent from a mixture based on its volatility. The mixture is heated to the point of vaporization, where the liquid solvent vaporizes into the atmosphere and leaves the solute behind. For example, to produce salt, seawater is collected in shallow pools and left to evaporate, leaving behind the salt.

- Distillation is used to separate liquid mixtures based on their boiling points. The mixture is heated to the lowest boiling point, causing that liquid to vaporize and condense back into a liquid in the condenser. For example, in a mixture of ethanol and water, heating the mixture to 78°C will evaporate only the ethanol, which is condensed and collected in another beaker.

- Chromatography separates components of a mixture based on their solubility and affinity to paper and a specific solvent. Generally, the more soluble the component, the higher on the paper they rise, allowing for each component to be identified. The specifics of chromatography are covered in more detail in Topic 2.2.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

S1.2: The atom

Atoms

In Topic S1.2, the primary focus is understanding atoms and the behavior of their electrons. This is very important because all chemical reactions will involve interactions between atoms and their electrons.

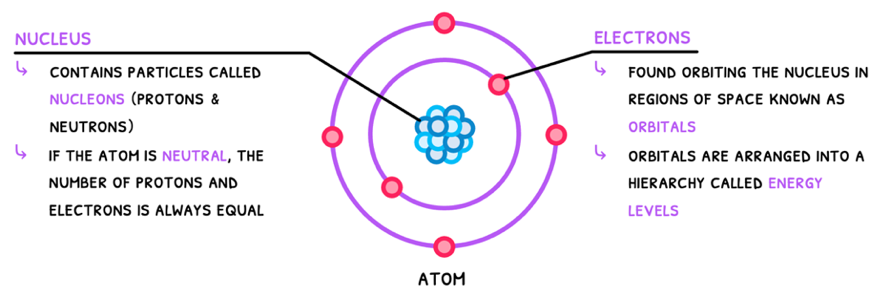

Atoms are defined as the smallest unit of an element. The IB requires you to know the Bohr model of the atom, which is composed of:

- A dense positively charged nucleus with protons and neutrons, termed nucleons.

- Negatively charged electrons in orbitals around the nucleus, arranged into energy levels/shells.

Although the Bohr model is technically incorrect, as electrons do not orbit the nucleus like satellites, it clearly communicates the concept of electrons having different energy levels. This is explored in more detail in Topic S1.3.

Additionally, you need to be aware of the basic properties of each component of the atom. This is succinctly summarized in the table below:

| Proton | Neutron | Electron | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative mass | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Relative charge | +1 | 0 | -1 |

Atomic notation

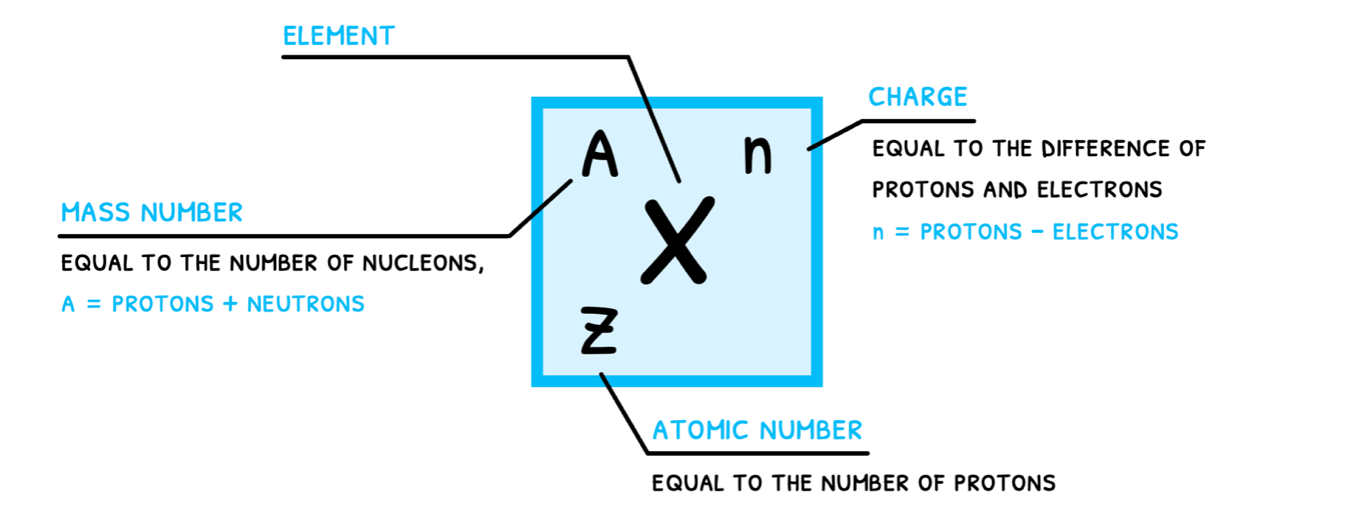

Since elements can appear in several forms (think Carbon-12, Carbon-13, and Carbon-14), it is important to clearly communicate which species is being used in any reaction. This is done by atomic notation, which communicates the following:

- Element (X) is the abbreviation of the element.

- Mass number (A) is equal to the number of nucleons.

- Atomic number (Z) is equal to number of protons.

- Charge (n) indicates the ionic state of the atom.

Note that for each element, the abbreviation and the atomic number will never change as they are linked to that element. If either changes, the element has changed.

On the other hand, mass number and charge regularly change in chemical reactions, giving rise to isotopes and ions, respectively.

Sail through the IB!

S1.2: Further atoms (HL)

Mass Spectrometry

Lastly, awkwardly nestled in this subtopic is the idea of mass spectrometry. In this subtopic, you need to understand that a mass spectrometer is a device used to:

- Determine the fragments of a compound, covered in more detail in Topic S3.2 HL.

- Determine an element's relative atomic mass from its isotopic composition.

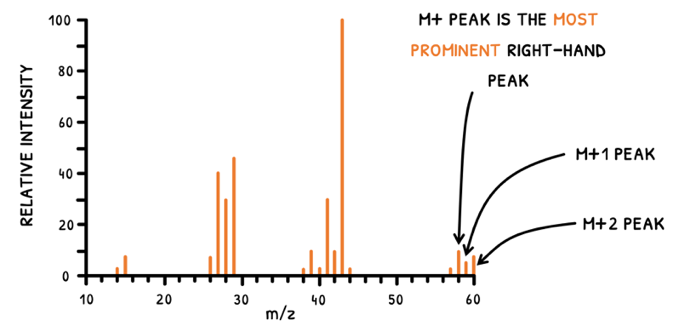

In both scenarios, the working principle is the same, but the produced information is used differently. To determine fragments, the highest peaks are used. However, you will notice that several peaks exist for each fragment, and particulary so at the M+ peak. Let's explain this:

- An element may have two isomers with different atomic masses.

- A mass spectrometer analyzes multiple molecules within a sample, averaging their fragment masses to produce the mass spectrum.

- If a sample contains two isomers with:

- A mass difference of 1, the M+ and M+1 peaks are seen.

- A mass difference of 2, the M+ and M+2 peaks are seen.

There are three main isotopes to learn to easily spot these peaks:

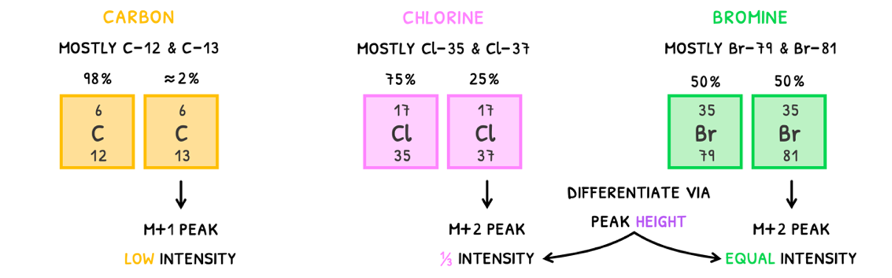

- Carbon - mainly exists as Carbon-12 (98%) and Carbon-13 (≈2%). The Carbon-13 isomer will produce an M+1 peak but because of its low abundance, the peak will have low intensity.

- Chlorine - mainly exists as Chlorine-35 (75%) and Chlorine-37 (25%). The Chlorine-37 isomer will produce an M+2 peak and because of its abundance, the peak will have an intensity of 33% relative to the M+ peak.

- Bromine - mainly exists as Bromine-79 (50%) and Bromine-81 (50%). The Bromine-81 isomer will produce an M+2 peak and because of its abundance, the peak will have an intensity equal to the M+ peak.

Abundance

The resulting abundance (a) of each isotope from mass spectograms is used to then calculate an element's relative atomic mass. Although molar mass will give the exact mass for an element, relative atomic mass is the mass of an element based on the proportional natural abundance (a) of each of its isotopes. The abundance of each isotope is the ratio of its natural occurrence to the total occurrence of all isotopes.

For example, nitrogen-14 makes up 99.6% of all naturally occurring nitrogen and nitrogen-15 makes up the other 0.4% of all naturally occurring nitrogen. Therefore, nitrogen-14’s abundance is 0.996 and nitrogen-15’s abundance is 0.004.

Following on from this, if an element has three isotopes x, y, and z, its relative atomic mass is calculated by the formula:

Ar=mxax+myay+mzaz

In trickier question, two isotopic masses (mx and my) may be given, but their abundances are not given. In this scenario, used the formula:

Ar=mx(ax)+my(1−ax)

Then, plug in the relative atomic mass, the given isotopic masses and solve for x using algebra!

S1.3: Electron configurations

Electromagnetic waves

Whilst you know about electrons and their orbitals in Topic S1.2, you also need to understand the discovery electron energy levels and transitions between them. This is evidenced by the absorption and release of energy by electrons in the form of an electromagnetic wave.

Electromagnetic waves are also known as electromagnetic radiation, which are a form of energy that travel as a wave. Remember that the basic components of waves are velocity (c), wavelength (λ), and frequency (f).

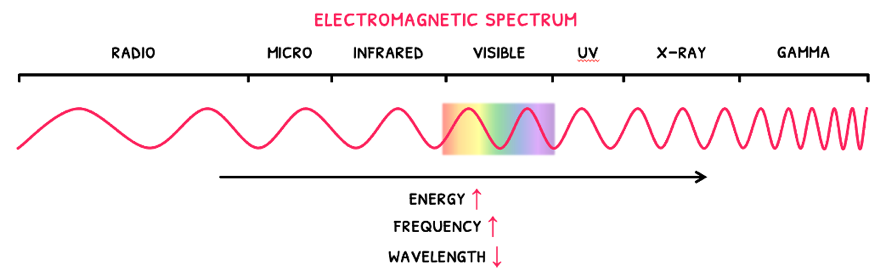

Whilst all electromagnetic radiation has a velocity of 3 x 108 ms-1, wavelength (λ), and frequency (f) change to give different wave types and energies. These are all described by the electromagnetic spectrum, wherein:

- As wavelength decreases, frequency increases.

- As wavelength decreases, energy increases.

Since the electromagnetic spectrum shows all the wave types, it is known as a continuous line spectrum. This is more specifically defined as a spectrum that shows all possible wavelengths. On the contrary, a line spectrum only shows particular wavelengths.

Absorption & emission spectra

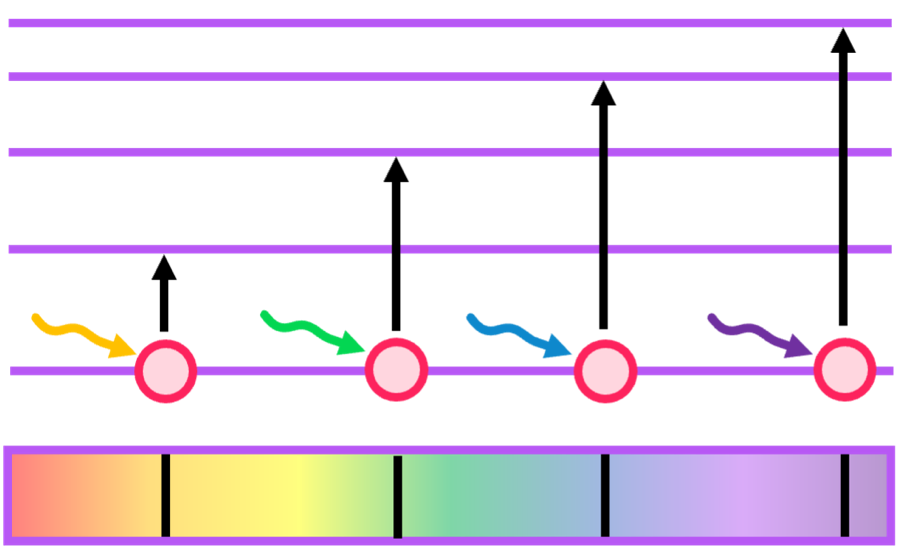

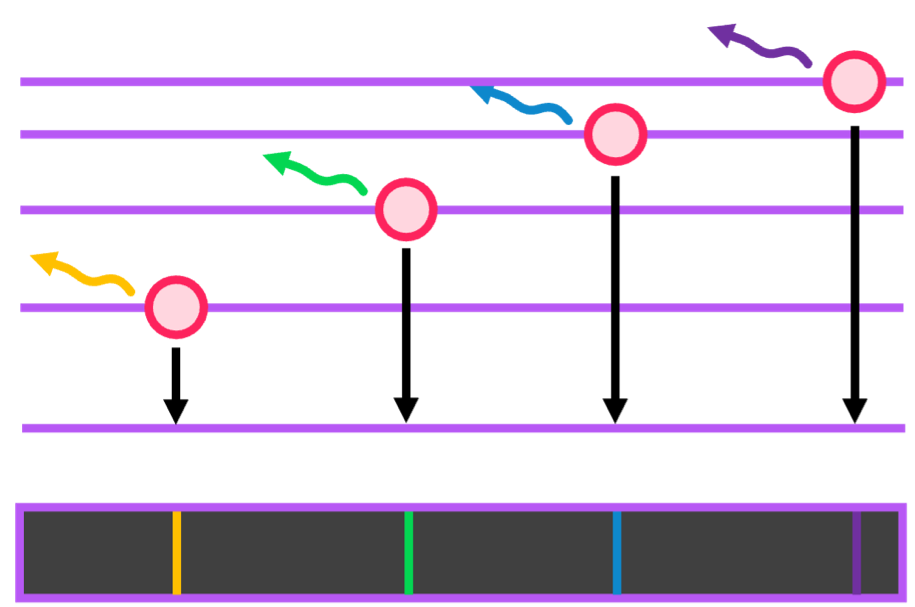

Relating this to electron energy transitions, when light shines on an element and is then turned off, two spectra are formed: absorption and emission.

- Absorption spectra - electrons will absorb specific wavelengths that allow them to promote to another energy level. These absorbed wavelengths are thus not detected, as shown below.

- Emission spectra - electrons will re-emit the wavelengths that they absorbed to demote to their base energy level. These emited wavelengths are thus detected.

The emission spectrum is an example of a line spectrum, and if you put both the emission and absorption spectra together, the continuous spectrum is reformed.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

S1.3: Further electron configurations (HL)

Calculating energy changes

In Topic S1.3, HL students need to be able to quantify the energy changes electrons undergo when they absorb or emit electromagnetic waves. Remember that from the electromagnetic spectrum that wave energy is proportional to its frequency (f). The formula for this is:

E=hf

In this, h is the Planck constant and equal to 6.63 x 10-34 Js. An alternative formula can be formed by substituting in the wavespeed equation.

c=fλ

λc=f

E=λhc

Ionization energy and trends

An additional concept you are expected to understand is that of ionization energy. Remember that if enough energy is supplied to an electron, it can escape the nucleus's grasp and go beyond the convergence limit, creating an ion.

This is the first ionization energy, defined the energy required to remove one electron from a mole of gaseous atoms, measured in kJ mol-1. Any subsequent ionizations have the terms second ionization energy, third ionization energy ... et cetera. The reaction can be described via the following chemical equation:

X(g) → X+(g) + e-

It is important to understand that only one of the electrons in the outermost shell, termed the valence shell, is removed from the atom, and that the energy required to achieve this is completely dependen on the charge attractions with the nucleus.

In Topic S3.1, common trends in the periodic table will be discussed. However, more detail is required for HL students when discussing ionization energy.

For this, and future trends, a few terms are commonly used so must first be defined:

- Electrostatic attraction - the electrical attraction of opposite charges between the positive nucleus and the negative electrons.

- Nuclear charge - the degree of attraction by protons in the nucleus to electrons.

- Shielding effect - the phenomenon that non-valence electrons block the nuclear charge from reaching the valence electrons.

- Effective nuclear charge - the actual nuclear charge that reaches the valence electrons and attracts them after the shielding effect.

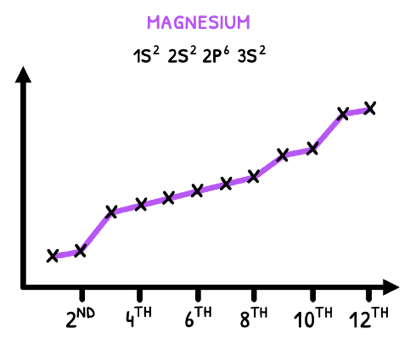

Whilst you will use these terms explain trends in Topic S3.1, in this topic you are expected to understand the trend in successive ionization energies. These are defined as the energies required to remove consecutive electrons from a mole of gaseous atoms, measured in kJ mol-1.

You are required to be able to explain this for any element, but the trend is based on the electronic configuration and is thus the same for any element.

To generalize this to any element, remember the following rules:

- For consecutive ionizations, ionization energy will increase due to an increase in effective nuclear charge.

- For ionizations from full s-orbitals, ionization energy will have a large increase due to the stability of a full s-orbital.

- For ionization from full p-orbitals, ionization will have an even larger increase due to a drop in energy level and shielding, significantly increasing effective nuclear charge and ionization energy.

When viewing magnesium's ionization energy graph, all these rules are in effect.

- Ionization energy increases from start to end.

- There is a larger increase in the 9th ionization as this takes the first electron from the 2s orbital.

- There is an even larger increase in the 3rd and 11th ionization energies as these remove the first 2p and 1p electrons, respectively.

S1.4: Moles

The mole

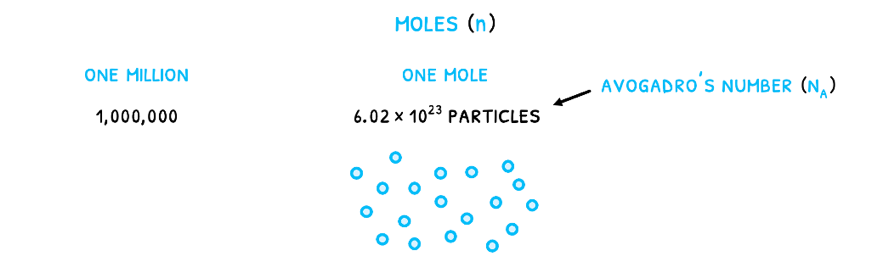

In reactions, substances are often measured in moles (n). This is a measure of the number of particles given by Avogadro’s number (NA) equal to 6.022 x 1023 particles/mole. It relates to the number of particles that would make Carbon-12 exactly 12 grams as the standard element. Therefore, just like one million is 1,000,000, one mole is 6.022 x 1023 particles.

Note that this describes the number of particles so 1 mole of any diatomic molecule, such as H2, has 1.2044 x 1024 atoms because every molecule (and therefore particle) has two component atoms.

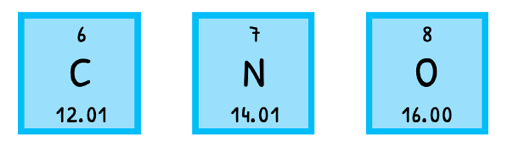

The mass of an atom can be expressed as molar mass (M), the mass of one mole of a substance in gmol-1. The most often used one is the relative atomic mass (Ar), the weighted mean molar mass of all naturally occurring isotopes of the element relative to Carbon-12. This is the case due to Avogadro's number.

Calculating molar mass is possible with the equation:

molar mass (M)=moles (n)mass (m)

Formula Mass

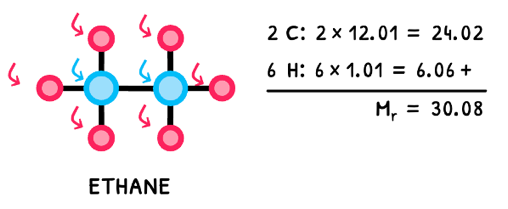

The relative atomic mass of each element is then used in further calculations. These often involve calculating the molar mass of a molecule. This is referred to as the relative formula mass (Mr), is the sum of the relative atomic masses of its components. For example, the relative atomic mass of hydrogen is 1.01 gmol-1 and of carbon is 12.01 gmol-1 so the relative formula mass of C2H6 is 30.08 gmol-1, as shown below!

Formulas

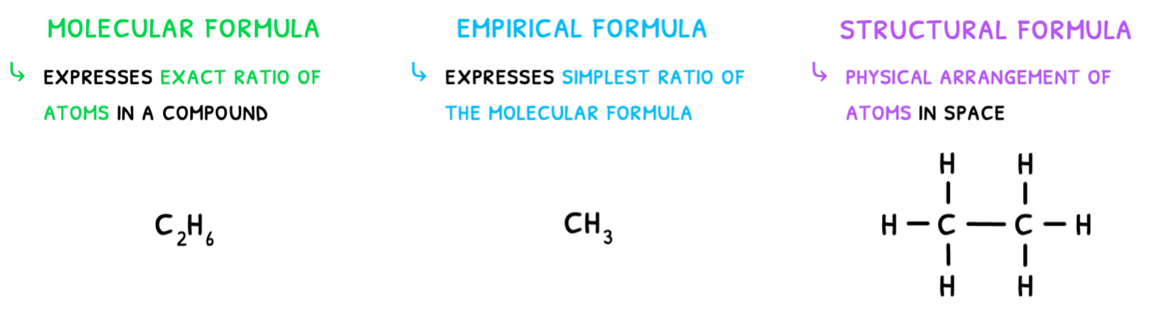

Lastly, when forming molecules and compounds, it is important to understand how to correctly communicate them. This can be done via three forms of formulas: molecular, empirical, or structural.

- Molecular formulae state the compound's atomic composition in the exact ratio they appear. For ethane, this is C2H6.

- Empirical formulae state the compound's atomic composition in the most simplified ratio. For ethane, the ratio is simplified to CH3.

- Structural formulae show the compound's atomic composition and the physical arrangment of the atoms in space.

Sail through the IB!

S1.5: Ideal gases

Ideal Gases

To complete your understanding Topic S1, the IB expects you to further understand the behavior of gases. Since different gases will behave differently in certain conditions, the concept of an ideal gas has been created to predict their behavior. An ideal gas has the following properties:

- No forces between particles.

- Perfectly elastic collisions.

- Particles have no volume.

- One mole occupies 22.7 dm3 at STP or 24.0 dm3 at RTP.

Note that real gases will only behave like ideal gases at moderate tohigh temperatures, low density, and low pressures.

The ideal gas equation thus relates the main properties of gases: pressure, volume, moles, and temperature. The formula for this is:

PV=nRT

In this formula, the gas constant (R) is 8.314 JK-1mol-1, whilst pressure is in kPa, volume is in dm3 and temperature in K. However, most of the time you will find that moles is kept constant pressure, volume, or temperature are changed. This changes the equation to:

T1P1V1=T2P2V2

Ideal Gas Laws

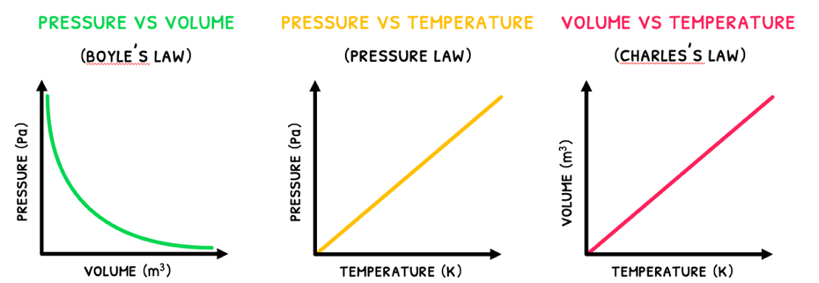

Together, pressure, volume, and temperature are thus considered the main factors of gases. Their effects on gas behavior are described by the ideal gas laws. These are as follows:

- Boyle's law - this states that the relationship between pressure and volume is inversely proportional when temperature stays constant. Gases exert a higher pressure when contained at smaller volumes due to an increased frequency of collisions with the container.

- Guy-Lussac's law - this states that the relationship between pressure and absolute temperature is directly proportional when volume stays constant. When temperature reaches absolute zero (0 K or -273°C) both kinetic energy and pressure is equal to 0.

- Charles's law - this states that the relationship between volume and temperature is directly proportional when pressure stays constant. Gases have more kinetic energy at higher temperatures and will collide with more frequency and energy. This requires more volume to fulfill the requirement of constant pressure.