IB Chemistry Topic 6 & 16 Notes

R3.1: Proton transfer

Proton transfer

Topic R3.1 focuses on proton transfer reactions, the most common of which are reactions involving acids and bases. However, their properties are rather complex and require an in-depth look to understand the full process. Acids and bases can be described by three theories:

- Ionic theory - involves the formation of protons.

- Brønsted-Lowry theory - involves the transfer of protons.

- Lewis theory - involves the transfer of electrons, so covered in Topic R3.4.

Ionic Theory

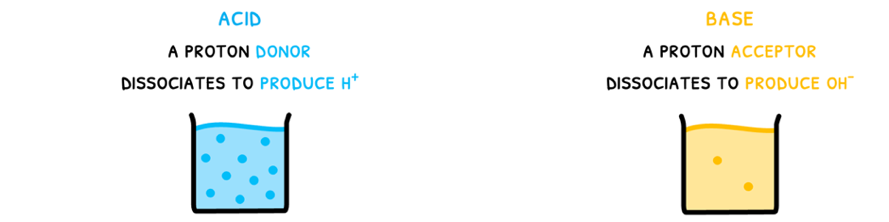

Let's start with ionic theory, which is very simplistic. It has two key principles:

- Acids dissolve in water to produce H+ at a concentration greater than 1.0 x 10-7 mol dm-3.

- Bases dissolve in water and can neutralize acids.

Brønsted-Lowry Theory

Brønsted-Lowry theory is more complicated. This also has two principles:

- Acids dissociate to produce H+, which is subsequently donated to another molecule.

- Bases dissociate to produce OH-, and subsequently accepts a proton.

Conjugate Acids and Bases

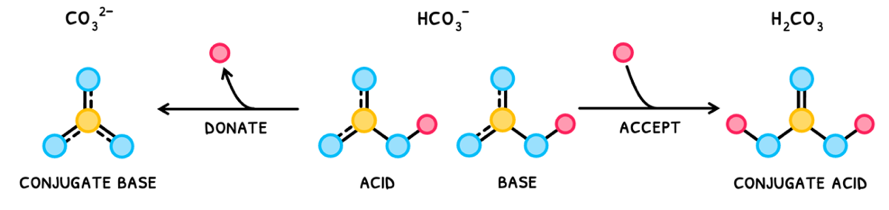

The species formed from these reactions are:

- Conjugate base - the ion formed by an acid donating a proton. As a result, this ion can now accept a proton and is thus a base.

- Conjugate acid - the ion formed by a base accepting a proton. As a result, this ion can now donate a proton and is thus an acid.

As you can see, a conjugate acid-base pair thus differs by one proton.

However, some species can act as both both Brønsted-Lowry acids and bases, which are called amphiprotic species. An example is HCO3-:

- It can donate a proton to become CO32-.

- It can accept a proton to become H2CO3.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

R3.1: Further proton transfer (HL)

Calculations for Acids and Bases

Whilst you learned the basics of acids and bases in the SL syllabus, you need to be able to perform calculations involving them in the HL syllabus.

For this, a handful of extra concepts need to be learned, including:

- pOH

- pKa

- Ka

- pKb

- Kb

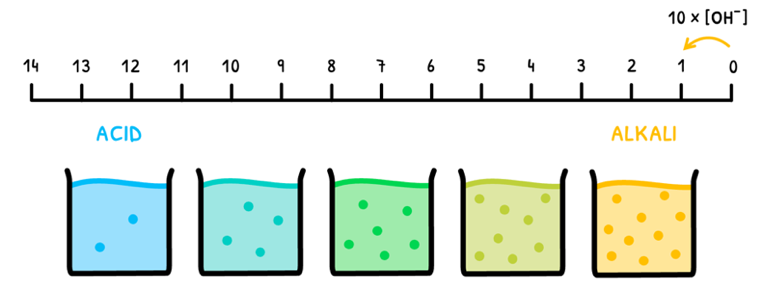

Calculating pOH

Let's start with pOH. Whilst pH is "power of hydrogen" to describe acidity, pOH is the "power of hydroxide" to describe alkilinity. Thus, it is simply a measure of OH- concentration. The formula for this is:

[OH−]=10−pOH

Taking the log of both sides, a more common formula appears. The formula for this is:

pOH=−log10[OH−]

Naturally, it is also possible to plot pOH as a log scale of OH- concentration. This runs in the opposite direction of pH from 14 to 0. However, a 10-fold change in OH- concentration still causes a change of 1 pOH.

The scale can again be divided into distinct sections;

- A pOH of 14 indicates that [OH-] = 10-14 mol dm-3, meaning the solution is strongly acidic.

- A pOH of 7 indicates that [OH-] = 10-7 mol dm-3, meaning the solution is neutral.

- A pOH of 0 indicates that [OH-] = 1 mol dm-3, meaning the solution is strongly alkaline.

Calculating pKw

Since pH is based off of Kw, it follows that pOH is too. Let's run through the math. Remember that:

Kw=[H+][OH−]

Just like pH and pOH, we can establish a "power of water" by taking its log so that:

pKw=−log10Kw

Applying this to the concentrations of H+ and OH- too, we get:

pKw=−log10[H+][OH−]

pKw=pH+pOH

At 298 K, it is important to understand that for any solution pKw = 14 (since Kw = 10-14). Thus:

pH+pOH=14

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

R3.2: Electron transfer

Electron transfer

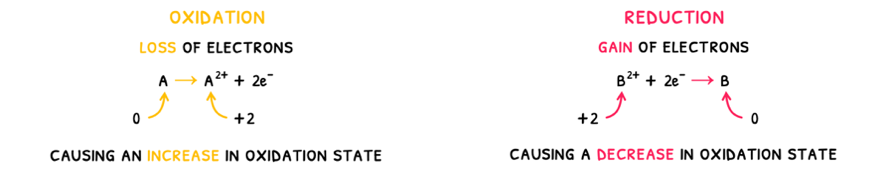

The second type of reaction you need to know about is electron transfer. This is typically subdivided into the oxidation and reduction of species, which can translate to the production of electrical energy. Within this, it is first important to understand what oxidation and reduction mean:

The old definitions state that:

- Oxidation is the process by which a species undergoes a loss of hydrogen or gain of oxygen.

- Reduction is the process by which a species undergoes a gain of hydrogen or loss of oxygen.

However, sometimes species neither gain nor lose hydrogen or oxygen, making it difficult to tell which processes is occurring. This led to the new definitions, which state that:

- Oxidation is the process by which a species undergoes a loss of electrons.

- Reduction is the process by which a species undergoes a gain of electrons.

A mnemonic that can be used to remember these definitions is OIL RIG: Oxidation Is Loss of electrons and Reduction Is Gain of electrons.

Oxidation States

However, when two compounds swap ligands, it is sometimes difficult to tell whether a species is losing or gaining electrons. Here, you need to remember the conecpt of oxidation state, as this can be revisited.

- Oxidation is the process by which a species undergoes a loss of electrons, causing an increase in oxidation state.

- Reduction is the process by which a species undergoes a gain of electrons, causing a decrease in oxidation state.

Thus, by observing how the oxidation state of an element changes, you can tell whether it oxidizes or reduces.

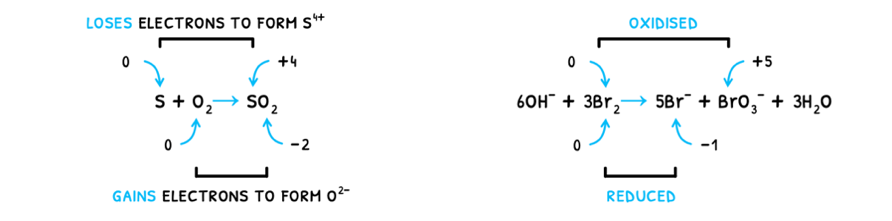

Redox Reactions

Now, naturally if in a reaction a species oxidizes, another species reduces. This can also occur within the same species. Example of both of these scenarios are shown below.

These types of reactions are called redox reactions, as both oxidation and reduction occur. Within this, there are two species:

- Oxidizing agent - the species that becomes reduced, and thus causes the oxidation of another species.

- Reducing agent - the species that becomes oxidized, and thus causes the reduction of another species.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

R3.2: Further electron transfer (HL)

The Electrochemical Series

Whilst in the SL syllabus you learned about redox and electrochemical cells, you need to know more about electrolytic cells in the HL syllabus. This starts by learning more about the electrochemical series.

The activity series indicates which metals are more reactive reducing agents, allowing you to predict which reactions occur in a voltaic cell. However, it does not give any quantitative information about the voltage generation that occurs, which is given in the electrochemical series in the data booklet.

We can break down the electrochemical series:

| Oxidised Species | ⇌ | Reduced Species | Eø |

|---|---|---|---|

Li+(aq) + e- | ⇌ | Li(s) | -3.04 |

K+(aq) + e- | ⇌ | K(s) | -2.93 |

Ca2+(aq) + 2e- | ⇌ | Ca(s) | -2.87 |

Na+(aq) + e- | ⇌ | Na(s) | -2.71 |

Mg2+(aq) + 2e- | ⇌ | Mg(s) | -2.37 |

Al3+(aq) + 3e- | ⇌ | Al(s) | -1.66 |

Mn2+(aq) + 2e- | ⇌ | Mn(s) | -1.18 |

H2O(l) + e- | ⇌ | 1/2 H2 (g) + OH-(aq) | -0.83 |

Zn2+(aq) + 2e- | ⇌ | Zn(s) | -0.76 |

Fe2+(aq) + 2e- | ⇌ | Fe(s) | -0.45 |

Ni2+(aq) + 2e- | ⇌ | Ni(s) | -0.26 |

Sn2+(aq) + 2e- | ⇌ | Sn(s) | -0.14 |

Pb2+(aq) + 2e- | ⇌ | Pb(s) | -0.13 |

- The standard electrode potential (Eø) of a half-cell indicates a species's tendency for reduction.

- More negative values (top of table) indicate a weak tendency to reduce. This means they are more likely to undergo oxidation and act as a reducing agent.

- More positive values (bottom of table) indicate a strong tendency to reduce. Thus, they are more likely to undergo reduction and act as an oxidizing agent.

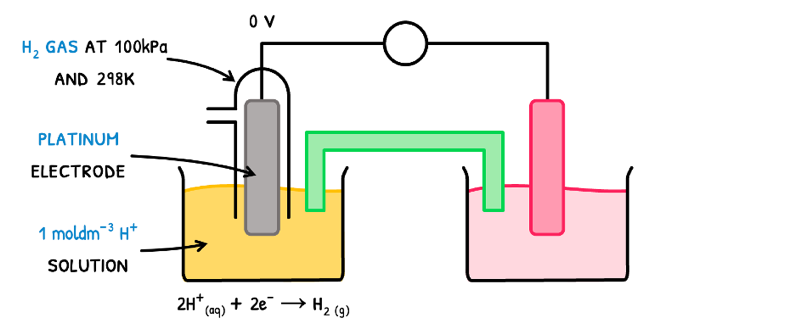

Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE)

It is important here to note that the electrode potential is standardized. The reference point is called the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE), which has a standard electrode potential Eø = 0 V.

The SHE is composed of:

- A platinum electrode.

- This is surrounded by a container containing H2 gas.

- This set-up is submerged in a 1.0 mol dm-3 H+ solution

- All conditions are at standard temperature and pressure (298 K and 100 kPa).

This half-cell is connected to another half-cell of itself. Since both reactions are equally spontaneous, neither occurs and the voltage difference between the electrodes is 0V.

Thus, when the SHE is connected to a half-cell of a species in the electrochemical series, the voltage difference between the two electrodes is the standard electrode potential.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

R3.3: Electron sharing

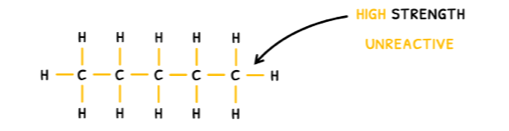

Structure of alkanes

The third reaction type you need to know about is electron sharing, which typically takes the form of free radical substitution. This occurs in alkanes because they have no functional group and consist purely of C-C and C-H bonds. As a result, their general formula is CnH2n+2.

Due to their structure, alkanes are non-polar so they only have weak London dispersion forces, making them volatile and insoluble in water. However, the high strength of the C-C and C-H bonds makes them unreactive.

Thus, the only reactions they undergo are with very reactive species called radicals. Thus, during free radical substitution, alkanes reacts with halogens in the presence of UV light to form a halogenoalkane and hydrogen halide. For example:

C2H6 + Cl2 → C2H5Cl + HCl

Free Radical Substitution of Alkanes

You need to know the process of free radical substitution in more detail. It occurs in three stages:

Initiation - during this, the halogen absorbs UV to form two halogen radicals, called homolytic fission. The movement of electrons is signified by curly half-headed arrows.

X2 → 2X•

- Propagation - during this, radicals react with the alkane, creating more radicals.

X• + CH4 → H3C• + HX

H3C• + X2 → CH3X + X•

- Termination - eventually, the radicals react with one another to cancel out.

2X• → X2

H3C•+ H3C• → C2H6

X• + H3C• → CH3X

R3.4: Electron-pair sharing

Electron-pair sharing

The last type of reaction you need to know about involves the sharing of electron pairs. During these reactions, two terms frequently come up:

- Electrophile - this is an electron-deficient reagent with a positive or partially positive charge that accepts electron pairs.

- Nucleophile - this is an electron-rich reagent with a negative or partially negative charge that donates electron pairs.

These will result in two different types of reactions occurring:

- An electrophile will accept an electron pair as a part of electrophilic substitution or electrophilic addition.

- A nucleophile will donate an electron pair as a part of nucleophilic substitution.

Electrophilic Addition

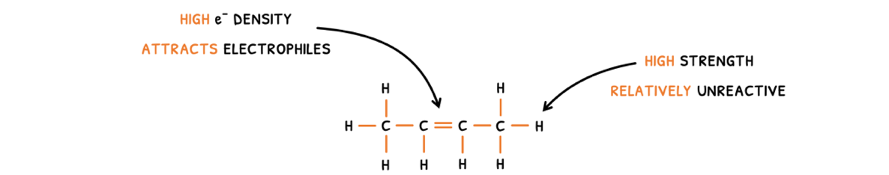

Let's begin with electrophilic addition. This is the process by which alkenes reacts with halogens or hydrogen halides to form halogenoalkanes, or water to form alcohols.

Alkenes are the species typically involved because they contain an alkenyl (C=C) function group and have the general formula CnH2n.

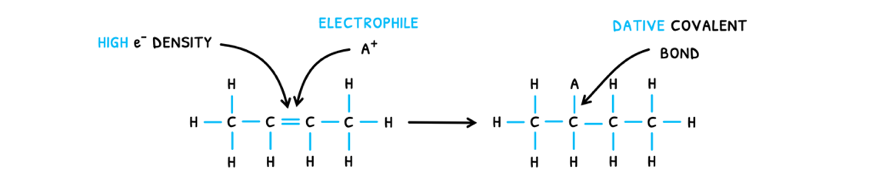

Although the C-C and C-H bonds make alkenes unreactive, the C=C is an area of high electron density that attracts electrophiles.

So, during electrophilic addition:

- The high electron density of the C=C bond attracts electrophiles.

- The C=C bond breaks to donate an electron to the electrophile, forming a dative covalent bond.

- This forms a positive carbocation, attracting a nucleophile.

- The nucleophile donates an electron to the carbocation, forming a dative covalent bond.

The products differ depending on the electrophile:

- Diatomic halogen - C2H4 + Br2 → C2H4Br2

- Halogen halide - C2H4 + HBr → C2H5Br

- Water - C2H4 + H2O → C2H5OH

Nucleophilic Substitution

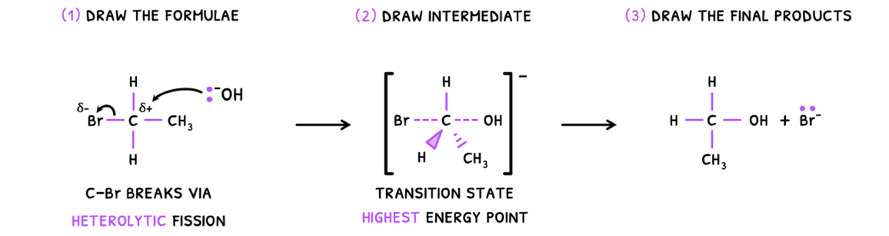

Second, nucleophilic substitution. Once a dihalogenoalkane or halogenoalkane is formed, it can swap nucleophiles. This involves the attack of a halogenoalkane by a nucleophile, swapping the halogenoalkane for the nucleophile. The nucleophile is typically OH- to produce an alcohol.

SL students are not expected to be able to explain this process in detail, but need a basic overview of what happens. During nucleophilic substitution:

- The C-X bond is polar, forming a dipole. This causes two events:

- A more reactive nucleophile (OH-) attacks the positive dipole by donating a pair of electrons.

- This forces the C-X bond to break via heterolytic fission, donating both electrons to the halogen.

- Depending on the mechanism, this may or may not form an intermediate transition state.

- Once the breaking and formation is complete, an alcohol and halogen ion are formed.

R3.4: Further electron-pair sharing (HL)

Lewis Theory

In Topic R3.1, the ionic and Brønsted-Lowry theories of acids and bases were introduced. In the HL syllabus, you need to know the third theory: Lewis theory.

In this theory, there are also two principles:

- An acid is a species that accepts a pair of electrons. This is due to their high electronegativity, so they are attracted to negative charges. They are termed electrophiles.

- A base is a species that donates a pair of electrons. This is due to their low electronegativity, so they are attracted to positive charges. They are termed nucleophiles.

Common Lewis acids and bases are shown in the table below:

| Lewis acids | Lewis bases |

|---|---|

BF3 H+ CH3+ | NH3 H2O OH- |

Amphoteric and Amphiprotic

You will find that the Brønsted-Lowry theory and Lewis theory are often used alongside one another depending on what is being donated/accepted, so you need to be familiar with them both.

When it comes to using both, however, two terms need to be defined:

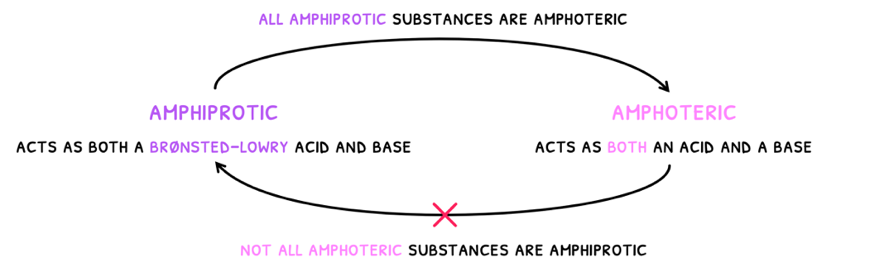

- Amphiprotic - these substances are able to both accept and donate a proton. By definition these act as both a Brønsted-Lowry acid and base.

- Amphoteric - these substance are able to act as both an acid and a base.

As a result, a species that can act as both a Lewis acid and bases would be amphoteric but not amphiprotic. You can thus say that:

- All amphiprotic substances are amphoteric.

- Not all amphoteric substances are amphiprotic.

More electron-pair sharing

Now that you are familiar with Lewis theory, you need to understand how Lewis acids and bases are involved in reactions. To finish the syllabus, you are expected to know more detail about the three remaining reactions:

- Electrophilic addition

- Nucleophilic substitution

- Electrophilic substitution