IB Biology Topic 2 Notes

A2.1: Origins of cells (HL)

Early Earth

Whilst it is important to understand the behavior of cells, it is also important to understand where they came from. This starts with understanding the conditions of early Earth that led to their development. It is hypothesized that prebiotic Earth was home to a reducing atmosphere. This means that no oxygen was present, as plants did not exist, and the atmosphere was rich in inorganic molecules such as H2, H2S, and NH3 with CO2 and CH4 as the carbon sources.

The physical conditions predicted on prebiotic earth consisted of:

- Oceans of water due to frequent asteroid bombardment.

- Ionising radiation from space made worse by the absence of O3 (ozone) in the atmosphere.

- Intense heat.

- Frequent electrical storms.

- Volcanic and thermal vent activity.

Prebiotic earth thus provided the conditions needed to produce simple organic molecules such as methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2), which became building blocks of more complex molecules such as amino acids, nucleotides, sugars, and lipids. These polymers may have spontaneously been produced in these conditions that ordinarily would not occur.

Miller & Urey

Miller & Urey aimed to investigate this theory that Early’s early atmosphere had conditions that favored chemical reactions forming complex organic compounds from inorganic reactants. They simulated Earth’s early atmosphere to generate complex compounds. The experiment was set up as follows:

- A gas mixture of methane, ammonia, hydrogen, and water vapor was made in a chamber.

- A water basin was heated to create steam and passed into the chamber.

- An electric arc inside the chamber was used to mimic lightning, triggering a chemical reaction between the gases.

- The apparatus was cooled down to allow the water to condense and pool back in the basin. In this collected water, new amino acids were found.

In total, Miller and Urey were able to synthesize more than the 20 naturally found amino acids. Whilst the experimental conditions cannot perfectly replicate Earth's early conditions, they were indicative that this theory of molecular generation was correct.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

A2.2: Cell structure

Cell theory

Cells are vital to the existence of living organisms. They were first viewed by Robert Hooke in bottle cork under a microscope. After years of observing cells, several scientists eventually developed the main tenets describing cells, called the cell theory. These three tenets are:

- Cells are the smallest unit of life.

- All living organisms are made up of cells.

- All cells come from pre-existing cells.

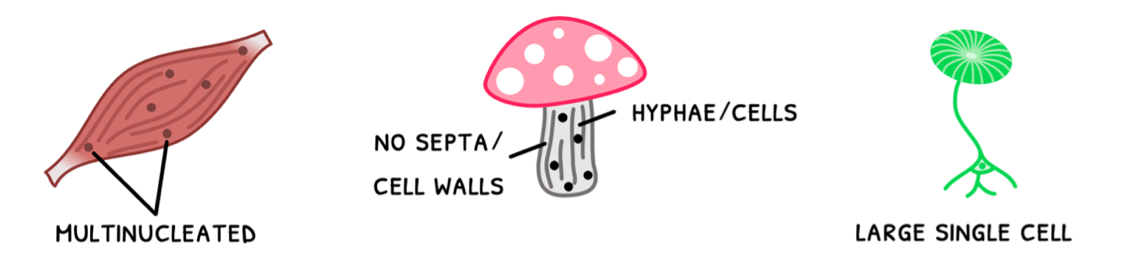

Although there are more tenets that have been added over the years, you are not expected to recite these on your IB exams. However, it is widely regarded that cells should only have one nucleus or not grow beyond a particular size. There are three exceptions to this you are expected to know: skeletal muscle, aseptate fungi, and giant algae.

- Skeletal muscle fiber cells are incredibly long. As a result, they need multiple nuclei per cell too maintain proper function in the whole cell, termed multi-nucleated.

- Fungi have thin fibrous cells called hyphae. Each hypha is divided by a cell wall, called a septum. Aseptate fungi do not contain septae, meaning they are also multi-nucleated.

- Giant alga is an incredibly large single celled organism, ranging from 0.5 to 10 cm in length.

Now that you know about the basics of the cells, it is important to note that the organisms that these cells form are divided into two types: unicellular organisms, composed of one cell of ≈10μm, and multicellular organisms, composed of more than one cell of ≈100μm. These each differ in structure, so let’s review this now.

Prokaryotes

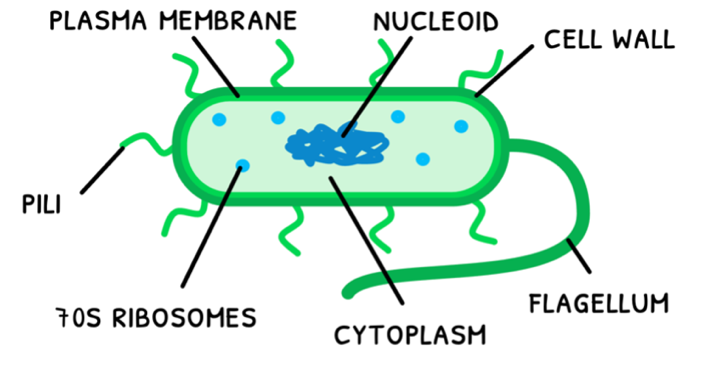

Unicellular organisms are referred to as prokaryotes, and their structure is succinctly described as a simple cell structure without compartmentalization. The common external components of prokaryotic cells that you are expected to remember are:

- The cell wall – this is a barrier composed of peptidoglycan that acts as a scaffold and maintains the cell’s shape. It is also the point of attachment of the pili and flagellum.

- The pili – these are hair-like structures that allow the prokaryote to interact with its external environment via adhesion and conjugation.

- The flagellum – this is a corkscrew-shaped tail-like structure that rotates to propel the prokaryote forward.

- The plasma membrane – this is a thin double layer of phospholipid, termed the phospholipid bilayer, that controls the transport of materials in and out of the cell.

The common internal components of prokaryotic cells that you are expected to remember are:

- The cytoplasm – this the internal fluid-like matrix where most cellular processes occur, and all organelles are located.

- The nucleoid – this is a naked circular loop of DNA. The term naked describes how this DNA is not associated with proteins.

- 70S ribosomes – these are small granular structures involved in many cellular processes, but primarily used to synthesize proteins. In prokaryotes, 70S describes their molecular size.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

A2.2: Further cell structure (HL)

Endosymbiotic theory

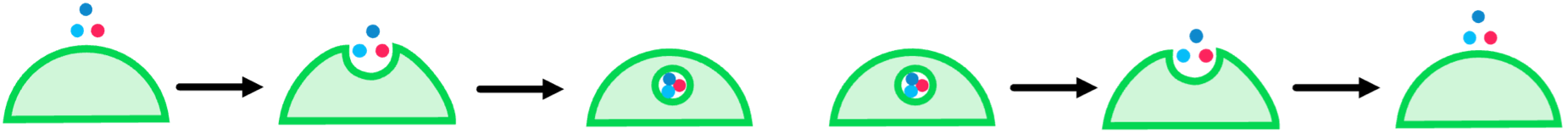

In the SL syllabus, you learned about the structure of eukaryotic cells. In the HL syllabus, you need to understand how they formed. This is is explained by the endosymbiotic theory. Endosymbiosis refers to the phenomenon of a smaller cell being endocytosed by a larger cell and then living inside the larger cell to perform a function for it. Thus, endosymbiosis is a combination of two words:

- Endocytosis – we know this term from Topic 1.4 but remember that it is the transport of materials into the cell.

- Symbiosis – the harmonious living together of two organisms.

This process is what formed the mitochondria and chloroplasts of animal and plant cells. This means that endosymbiosis must have occurred twice.

- An anaerobic cell takes in an aerobic bacterium via endocytosis. The bacterium now provides ATP for both cells via aerobic respiration and is protected from the external environment.

- This now aerobic cell takes in an autotrophic bacterium via endocytosis. The bacterium now provides nutrients for both cells via photosynthesis and is protected from the external environment.

However, we cannot just take this information for granted. The IB expects you to remember the evidence that supports the endosymbiotic theory. There are three main points to remember:

- Both mitochondria and chloroplasts have a nucleoid and 70S ribosomes. This provides evidence for their origins as prokaryotes, as eukaryotes do not have these.

- This theory is further supported by the fact that in preparation for mitosis, mitochondria and chloroplasts independently undergo binary fission to replicate themselves, a process unique to prokaryotes.

- Finally, both mitochondria and chloroplasts have a double membrane. This provides evidence for endocytosis, as this process would envelop a normal bacterium in a second membrane.

Multicellularity

You now know about the origin of eukaryotic cells, but you are also expected how these developed into multicellular organisms. They are thought to have developed when:

- Single cells clumped together to form colonies.

- In these colonies, some cells adapted more specialized roles than others depending on their location.

- This formed a pre-cursor to a multicellular organism.

Whilst many single-celled organisms exist, plants, animals, many algae and fungi have repeatedly evolved after extinction events. The natural tendency for eukaryotic cells to group together into multicellular organisms indicate the advantages of a larger body cell and cell specialization are considered useful.

Cell differentiation

This ability for cells to develop and specialize into specific cell types is called differentiation. As the different cell types grow together, they begin to produce small-scale tissues, organs, and organisms that repeatedly evolve to grow bigger.

However, you are expected understand how cell differentiation occurs:

- Environmental changes trigger signalling cascades within the cell.

- This causes a change in the epigenetic patterns of the cell, particularly its methylation pattern.

- This results in a change of gene expression - turning some genes on and others off and adjusting protein production.

- This leads to a change in a cell's behavior and function.

Thus, environmental factors cause changes in genetic expression patterns to cause cell differentiation.

A2.3: Viruses (HL)

Viruses

Viruses are inert and acellular pathogens that infect other organisms. Whilst there are many types of viruses with variable shapes and appearances, they are similar in structure and share the following features:

- Small fixed size

- Protein capsids

- No cytoplasm

- Genetic material as either DNA or RNA

- Few or no enzymes

Further to this, some viruses are enveloped in host cell membrane. This is advantageous because it can:

- Facilitate viral entry into the host cell

- Evade immune system recognition

- Protect the genetic material

You are not expected to know examples of enveloped and unenveloped viruses, but examples of viruses you need to be aware of include:

- Bacteriophage λ

- Coronavirus

- HIV

Viral life cycles

Since viruses are non-living and do not have a metabolism, they are incapable of growing or reproducing independently. They thus rely on cells for their energy supply, nutrition, protein synthesis and other life functions. They in which they acquire this can occur via one of two cycles: the lytic cycle or the lysogenic cycle. Both will be explored in the context of bacteriophage λ.

In the lytic cycle:

- The virus attaches to the host cell and injects its viral genome.

- This degrades the host genome, leaving only the viral genome.

- The host's cellular machinery replicates the viral genome and synthesizes viral proteins.

- These are assembled into new viruses and released from the cell.

- The release process kills the cell, and the new viruses restart the cycle.

In the lysogenic cycle:

- The virus attaches to the host cell and injects its DNA.

- The DNA integrates with the host cell's DNA and becomes part of its genome.

- The host cell replicates into two daughter cells, replicating the virus's DNA.

- As part of their gene expression, these cells now produce viruses.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B2.1: Membranes and transport

Hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules

You have previously learned that all cells contain a plasma membrane, which controls the transport of materials in and out of the cell. The structure as we know it today was formed from a series of models. However, before this is covered, it is important to understand a few key concepts: hydrophobic and hydrophilic molecules.

- Hydrophobic molecules are repelled by water and so only bond with other hydrophobic molecules. Lipids (fats) are an example of a hydrophobic molecule.

- Hydrophilic molecules are attracted to water and so only bond with water or other hydrophilic molecules. Proteins are an example of a hydrophilic molecule.

- Amphipathic molecules are partly hydrophobic and partly hydrophilic, allowing them to bond with water/hydrophobic molecules and hydrophobic molecules at the same time.

Lipid bilayers

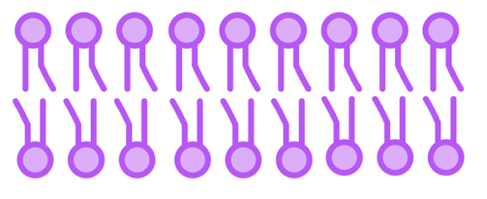

An example of an amphipathic molecule is a phospholipid, a type of fat that is a central component of the plasma membrane. Remember that phospholipids have a hydrophilic phosphate head and two hydrophobic lipid tails. As a result, lipids in the plasma membrane form a continuous sheet-like bilayer in water-based environments:

- Hydrophilic phosphate heads face outwards towards water.

- Hydrophobic lipid tails face inwards towards each other to stabilize the bilayer.

- This structure means that the membrane core has a low permeability to large molecules and hydrophilic particles, including ions and polar molecules.

Overall, having a lipid bilayer is thus an effective barrier between aqueous solutions and capable of controlling transport in and out of hte cell.

Fluid mosaic model

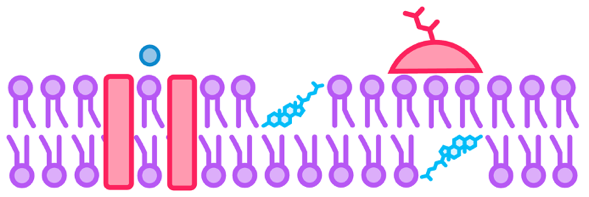

However, the membrane has more components than the phospholipid bilayer. The model for this is called the fluid mosaic model, whose main components are:

- The membrane is a lipid bilayer composed of phospholipids and cholesterol, with the hydrophilic phosphate heads facing outward and the hydrophobic lipid tails facing inward.

- The phospholipids are fluid and able to flow freely throughout the membrane. Cholesterol impedes phospholipid flow, making the membrane stiffer and reducing its permeability to

- Proteins do not form an outer layer, but instead are found on the outside of the phosphate heads, termed peripheral proteins, or pass through one or both lipid layers, termed integral proteins.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B2.1: Further membranes and transport (HL)

Membrane fluidity

In the HL syllabus, you are expected to understand more detail about membranes and membrane models. This begins with membrane fluidity, which changes depending on the type of lipid involved in the bilayer:

- Unsaturated fatty acids have a bend in their chain, resulting in a lower density and melting point. As a result, it makes membranes more fluid and flexible at body temperature.

- Saturated fatty acids have straight chains, resulting in a higher density and melting point. As a result, it makes membranes more rigid and strong at body temperature.

- Cholesterol sits inside of the bilayer and interacts with the phosphate head of one phospholipid and the lipid tail of another phospholipid binding them together. It thus acts as a modulator of membrane fluidity by stabilizing membranes at higher temperatures and preventing stiffening at lower temperatures.

As a result, plasma membrane need to strike a balance between fluidity to coordinate important processes and rigidity to maintain structural integrity. The degree of composition is thus dependent on the temperature of the organism's habitat:

- Cold habitats - have a higher amount of unsaturated fatty acids to maintain fluidity at low temperatures.

- Normal habitats - have an even amount of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids.

- Warm habitats - have a higher amount of saturated fatty acids to maintain rigidity at high temperatures.

Vesicular transport

This fluidity of the membrane allows cells to form variable shapes and form barriers together. However, in the context of transport, it allows the movement of large materials, or materials in bulk, into and out of the cell by using vesicles. Vesicles are spheres of phospholipid bilayer, as shown below, formed when the pinching off the plasma membrane. This allows for two modes of transportation: endocytosis and exocytosis.

- Endocytosis is the transport of large materials, or materials in bulk, into the cell. The process for this is:

- Materials come near the plasma membrane.

- Then, plasma membrane invaginates to engulf the materials.

- Once engulfed, the plasma membrane pinches off to form a vesicle, which moves through the cytoplasm to its end destination.

- Exocytosis is the transport of large materials, or materials in bulk, out of the cell. The process for this is:

- The Golgi bodies envelop material in a vesicle.

- This moves to the plasma membrane and fuses with it, releasing the contents.

- Afterwards, the membrane flattens to its original shape.

Gated ion channels

Now that you know about membrane fluidity and vesicular transport, you are expected to know more detail about specific transport methods. This begins with gated ion channels, including the potassium pump and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.

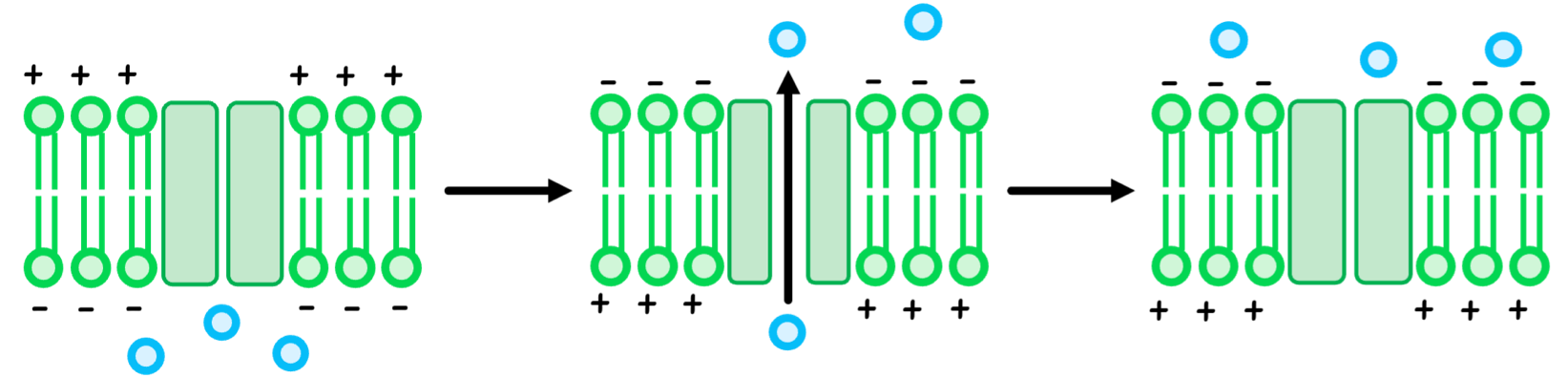

Let's start with the potassium pump, which is a voltage-gated ion channels found in neurons. This means that its opening and closing is regulated by the membrane potentials. This process occurs as follows:

- When the neuron is at rest, its internal charge is negative relative to the outside, keeping the potassium channel closed.

- When the neuron fires a signal, its internal charge becomes positive relative to the outside, opening the potassium channel.

- For a moment, potassium ions undergo facilitated diffusion to leave the neuron.

- When the internal charge quickly drops again to become negative, the potassium channel closes again.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B2.2: Organelles & compartmentalisation

Organelles

You previously learned the basics of cellular structure, including the compartmentalization of eukaryotes into organelles. Organelles are defined as discrete subunits of cells adapted to perform specific functions. You are expected to understand the organelles include:

- Nucleus

- Endoplasmic reticulum

- Golgi apparatus

- Mitochondria

- Chloroplasts

- Vacuoles

- Vesicles

- Ribosomes

- Plasma membrane

Note that the cell wall, cytoskeleton, and cytoplasm are not considered organelles as they are structural components that do not necessarily perform specific functions.

Compartmentalization

Remember that compartmentalization refers to the separation of organelles from the rest of the cell to localize specific functions in one area. In the cytoplasm, this has several advantages:

Metabolites and enzymes can be concentrated into specific organelles and can be kept there, not affecting the other organelles.

The vacuole is an example of this, as it is hypertonic and contains many metabolites required to retain water via osmosis. This would not be possible if it was not separated by a membrane.

Incompatible biochemical processes can be separated so that the enzymes are not affected by other enzymes and vice versa.

The lysosome is an example of this, as its digestive enzymes are fantastic for digestion of endocytosed materials, but if present in the cytoplasm would digest the cell from the inside.

Additionally, separation of the nucleus from the cytoplasm is worth discussing. This is advantageous because:

- It protects the DNA from external factors and enzymes present in the cytoplasm.

- It separates transcription from translation, allowing for post-transcriptional modification.

Without this separation, DNA is more susceptible and easily altered, increasing the rate of mutation, and alternative splicing cannot occur, reducing the number of proteins that can be produced from one gene.

B2.2: Further organelles (HL)

Mitochondrial adaptations

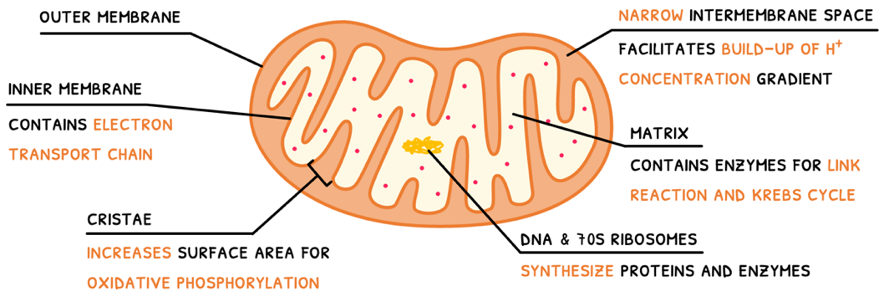

In the HL syllabus, you need to know more detail about specific organelles, beginning with the mitochondria. Remember that the link reaction, Krebs cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation all occur in the mitochondria, for which is has certain adaptations:

- Outer membrane - this separates the mitochondria from the rest of the cell.

- Inner membrane - this contains the electron transport chain and ATP synthase for oxidative phosphorylation.

- Cristae - folds of the inner membrane to increase the surface area for oxidative phosphorylation.

- Intermembrane space - the narrow space between the inner and outer membrane, which facilitates a rapid build-up of a H+ concentration gradient.

- Matrix - the mitochondria's cytoplasm, which contains the enzymes required for the link reaction and Krebs cycle.

- DNA & 70S ribosomes - the nucleoid and 70S ribosomes to synthesize its proteins and enzymes.

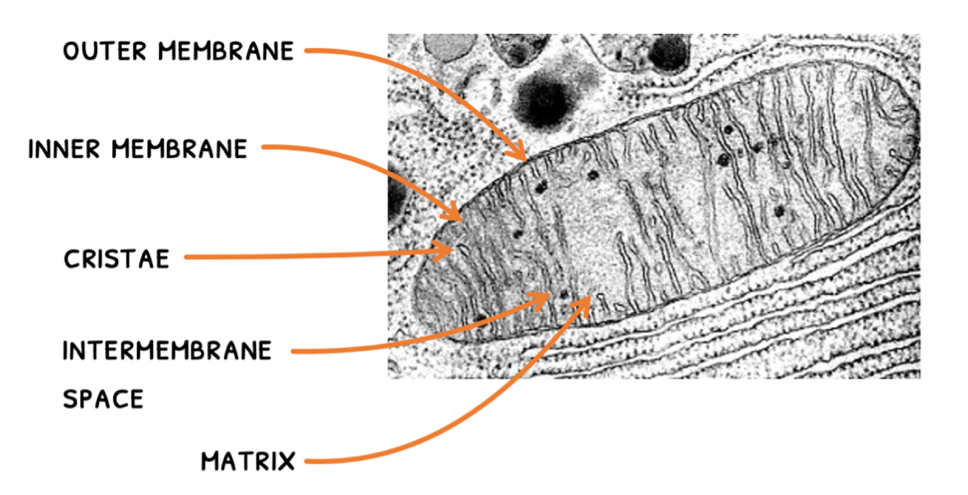

In recent years, electron tomography has been able to 3D visualize the mitochondria. Whilst a neat trick, you need to be able to label the same structures on a 2D electron micrograph:

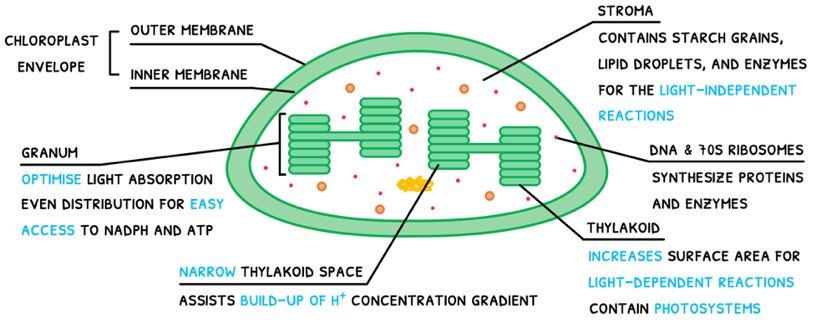

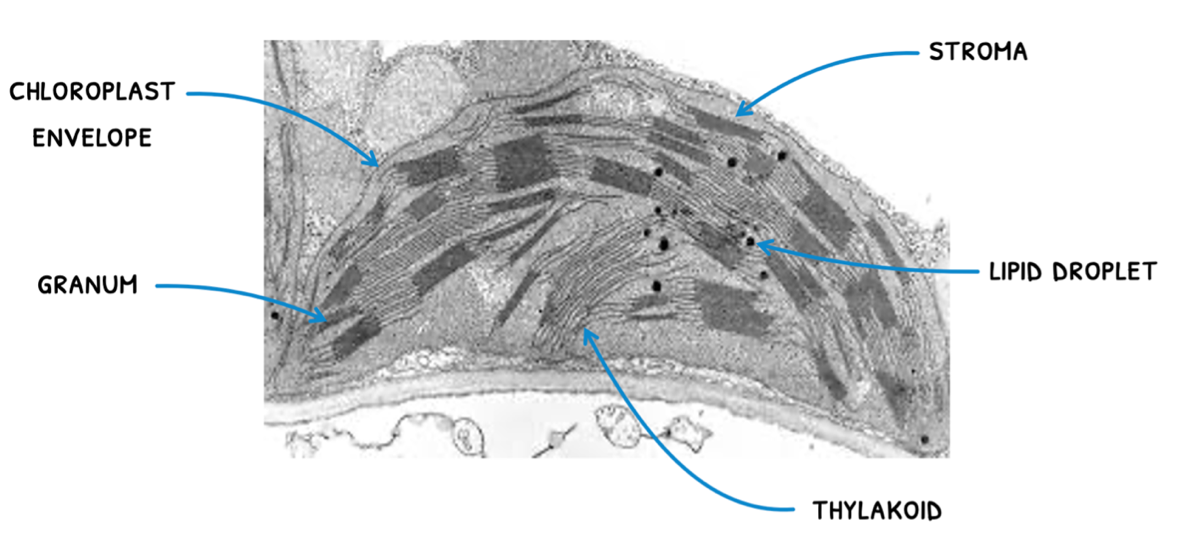

Chloroplast adaptations

Next, you need to know about the mitochondria. Remember that the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis all occur in the chloroplast, for which is has certain adaptations:

- Chloroplast envelope - composed of the inner and outer chloroplast membranes, this separates the chloroplast from the rest of the cell.

- Stroma - the chloroplast cytoplasm, which contains starch grains, lipid droplets and enzymes, all required for the light-independent reactions.

- Thylakoids - systems of internal membranes that increase the surface area for the light-dependent reactions.

- Thylakoid membrane - contains photosystems, the electron transport chain, and ATP synthase for the light-dependent reactions.

- Grana - towers of thylakoids adapted to optimize light absorption and evenly distributed throughout the stroma for easy access to NADPH and ATP.

- Thylakoid space - a narrow space that allows the quick build-up of the H+ concentration gradient.

- DNA and 70S ribosomes - used to synthesize proteins and enzymes.

You must also be able to recognize these structures in an electron micrograph:

Sail through the IB!

B2.3: Cell specialisation

Stem cells

You previously learned about the basic components of eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. In prokaryotes, this is all there is to the organism. However, in eukaryotes are larger multicellular organisms, requiring many different types of specialized cells. These all originate from a zygote, which undergoes mitosis into unspecialized cells. These are called stem cells, which are capable of dividing endlessly and specializing along different pathways via a process called differentiation.

The process of differentiation in the early-stage embryo is directed by external chemical called morphogens. These function as follows:

- Source cells secrete morphogens at different parts of the embryo as a positional guide.

- This will form a side with a low morphogen concentration and another side with a high morphogen concentration, forming a gradient.

- The morphogen then act on nearby cells to generate a change in gene expression, causing differentiation.

- Thus, cells on the high concentration side differentiate into the target tissue, whereas cells on the low concentration side do not.

This is thus a gradient of gene expression, will results in the formation of tissues in specific locations. As these differentiate and grow as according to the gradients, they end up forming organs, and then the whole body.

Thus, this process is necessary in embryonic development, growth into adulthood, and continual cell renewal throughout life.

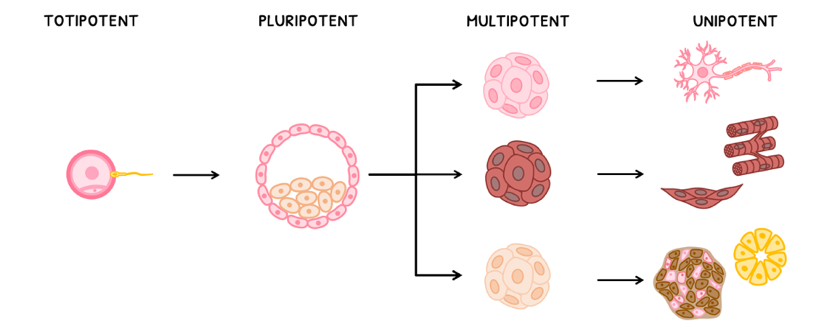

There are four different types of stem cells you need to know about: totipotent, pluripotent, multipotent, and unipotent stem cells.

- Totipotent - embryonic stem cell type that can develop into any type of cell in the body.

- Pluripotent - embryonic stem cell that can develop into many types of cells in the body.

- Multipotent - non-embryonic stem cell that can develop into several types of cells in the body.

- Unipotent - non-embryonic stem cell that can develop into one type of cell in the body.

Sources of stem cells

Due to their capacity to differentiate into different cell types, stem cells are often used in therapeutic settings. However, before they are used, they need to be sourced. It is generally the trend that the less developed the source, the more undifferentiated the stem cells are and the more therapeutic use there is. However, the less developed the source, the less biomarkers it has, and the less compatible it is. There are three sources you need to know about: embryos, the umbilical cord, and adults.

- Embryonic - these cells are contained within embryos. As a result, they are usually pluripotent but not fully compatible with patients.

- Cord blood - these cells are found in umbilical cord blood. As a result, they are multipotent and fully compatible with patients.

- Adult - these cells are found in adults. All of these are compatible, but most adult cells are unipotent, with some being multipotent.

You are expected to remember two types of stem cell niches in adults, including bone marrow and hair follicles.

- Bone marrow stem cells are located in the bone marrow. There, they divide and differentiate into red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets, replenishing their numbers as they die cyclically every few weeks.

- Hair follicle stem cells are located in the bulge of a hair follicle. There, they divide and differentiate into hair follicle cells, sebaceous gland cells, and epidermal cells, replacing hair and skin as they are lost.

Sail through the IB!

B2.3: Further cell specialisation (HL)

Surface-to-Area Volume

Now that you know about cell specialization, you are expected to understand the several adaptations cells develop to better perform their function. This begins with adaptations for an increased surface-to-volume ratio. This is typically done by:

- Reducing cell diameter

- Flattening or elongating the cell

- Making large membrane invaginations

- Forming hair-like structures called microvilli

Using this, cells shaped like or cylinder with microvilli or invaginations will have a greater surface area than a sphere of the corresponding volume. Two examples you need to remember are:

- The microvilli contained in luminal cells of the proximal convoluted tubule. These maximize surface area for efficient diffusion of substances whilst maintaining cell shape to form a tube.

- The flattened disc shape of erythrocytes with a large invagination on either side. This increases surface area for oxygen to diffuse and bind to haemoglobin.

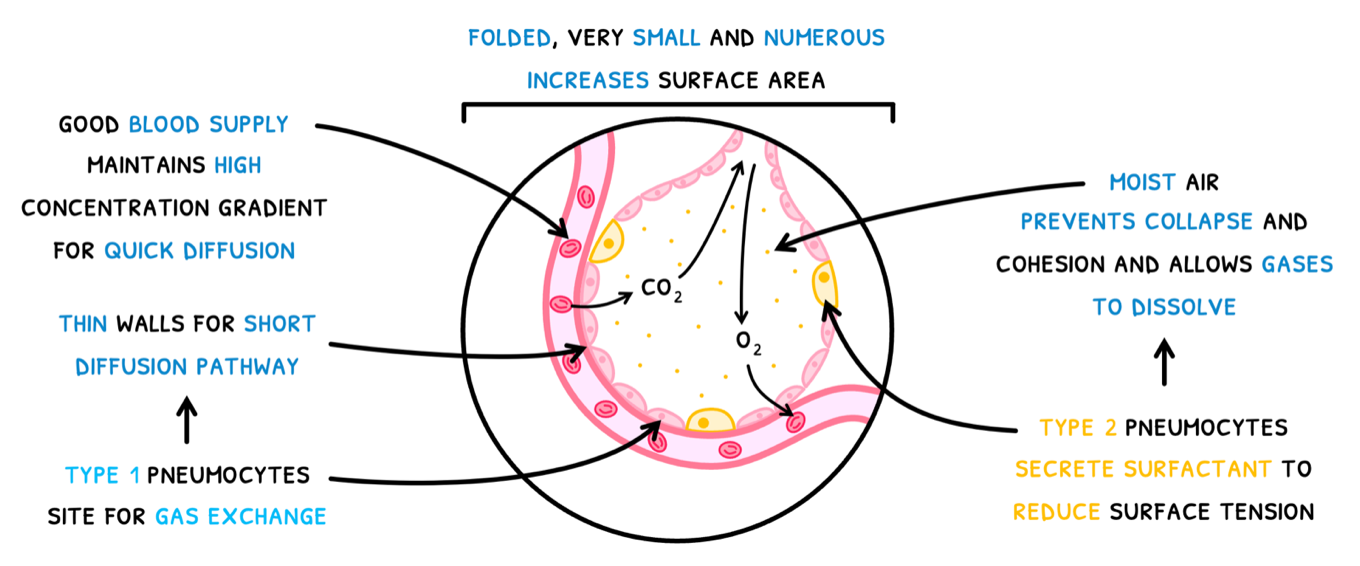

Alveoli

Next, alveoli. They contain several important adaptations to effectively perform gas exchange:

- Alveoli are folded, very small and very numerous, increasing the surface area for gas exchange.

- They have a good blood supply, maintaining a high concentration gradient to allow gasses to diffuse more quickly.

- They contain Type I pneumocytes, which have extremely thin walls to provide a short diffusion pathway. They thus act as the site of gas exchange.

- They contain Type II pneumocytes, which which secrete a solution known as surfactant. This makes the alveoli moist to:

- Reduce surface tension.

- Prevent collapse and cohesion of the walls.

- Allow gasses to dissolve and passively diffuse into the blood.

Muscle cells

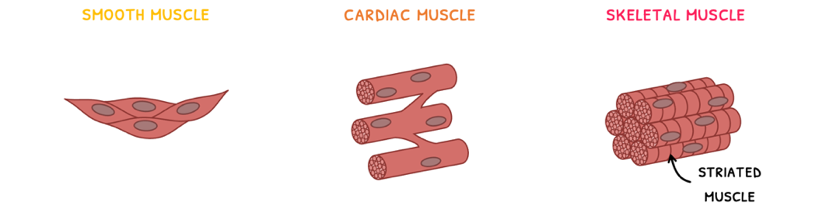

Next, muscle cells. Humans contain three types of muscle: smooth muscle found in the alimentary canal, cardiac muscle found in the heart, and skeletal muscle found in classic muscle.

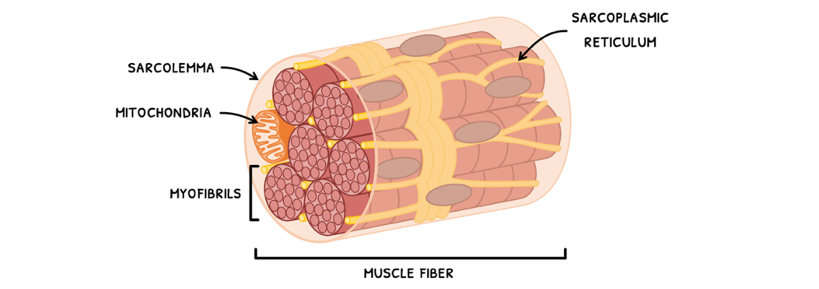

Skeletal muscle, also known as striated muscle, is easily recognizable due to its striations. These striations are a result of its structure. The tissue is composed of many muscle fibers bundled together into fasciculi. Each muscle fiber is formed from the fusion of embryonic muscle cells – hence why each muscle fiber is multi-nucleated. You are expected to know the detailed structure of a muscle fiber. It is composed of:

- A sarcolemma – the plasma membrane of the muscle fiber.

- Myofibrils – these are the long contractile fiber organelles of a muscle fiber.

- Sarcoplasmic reticulum – this is a network of tubules within the muscle fiber that stores calcium ions and acts to coordinate contraction across the whole fiber.

- Mitochondria – in abundant supply, these provide the large amounts of ATP necessary for contraction.

Sail through the IB!

C2.1: Chemical signalling (HL)

Receptors

You now know about cell origin, structure, function, and differentiation. The next step is to understand how cells are able to generate responses to environmental factors or other cells via receptors. These are defined as protein with binding sites for specific signalling chemicals, called ligands. Note that receptors are specific to their particular ligand to ensure efficient and appropriate responses, preventing unnecessary energy expenditure. There are two types of receptors you are expected to be aware of:

- Intracellular - found within the cell’s cytoplasm or nucleus. These receptors bind hydrophobic ligands able to cross the cell membrane.

- Extracellular (transmembrane) - found spanning the cell membrane with regions both inside and outside the cell, these receptors bind hydrophilic ligands that cannot cross the cell membrane.

There are number of different types of intracellular and transmembrane receptors. Regardless of the receptor type, the basic process of signal transduction is as follows:

- A ligand binds to a receptor on the plasma membrane.

- This causes a change in receptor conformation, which starts the signal transduction process.

- During this, a chemical cascade produces second messenger chemicals that head to a target site.

- There, they activate a particular process that generates a cellular response.

Note that some intracellular receptors are present at the target site and can directly activate a cellular response.

Quorum sensing

An example you need to be aware of is quorum sensing in bacteria. This is a process by which bacteria communicate cell density to one another.

- Quorum sensing bacteria secrete ligands called autoinducers into the extracellular matrix (ECM).

- These can diffuse back into the cell and neighboring cells.

- When there is a high cell density, there a high extracellular autoinducer concentration, causing a high diffusion into cells.

- If autoinducers are above a threshold concentration, they binds to internal receptors to trigger a change in gene expression.

- This results in a coordinated response of the cells to regulate motility, virulence, and symbiosis.

An example of quorum sensing occurs in the symbiotic relationship between the Hawaiian Bobtail squid and Vibrio fischeria, a bioluminescent bacteria. The hatchling squid collect the bacteria in their light organs and provide them with glucose and amino acids. In turn, the squid uses the bacteria for camouflage via counter-illumination, triggered by quorum sensing.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C2.2: Neural signalling

Neurons

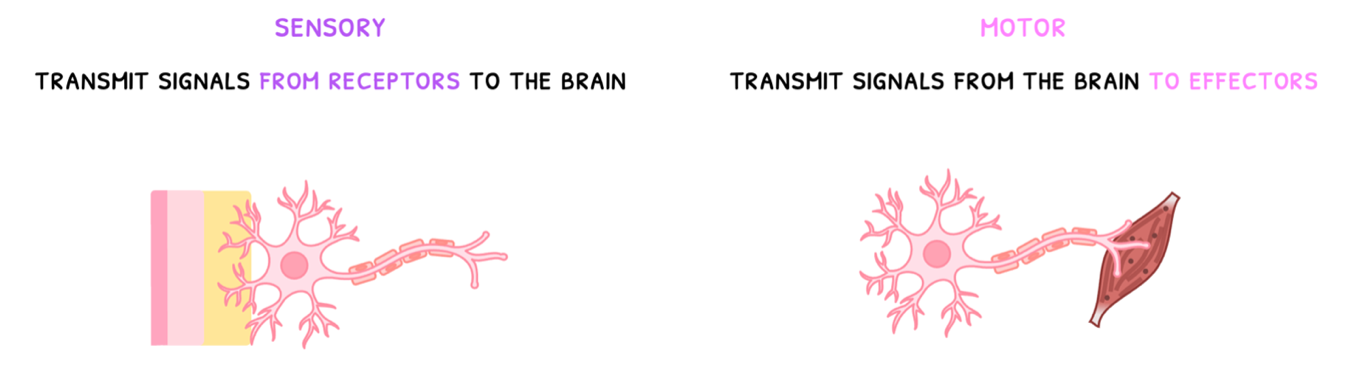

In Topic C2.2, the focus is on the nervous system. Although there are many cells that compose the nervous system, you only need to focus on one type: neurons. These are primarily responsible for transmitting electrical impulses and divided into two types:

- Sensory neurons - these transmit signals from receptors to the brain.

- Motor neurons - these transmit signals from the brain to effectors (muscles).

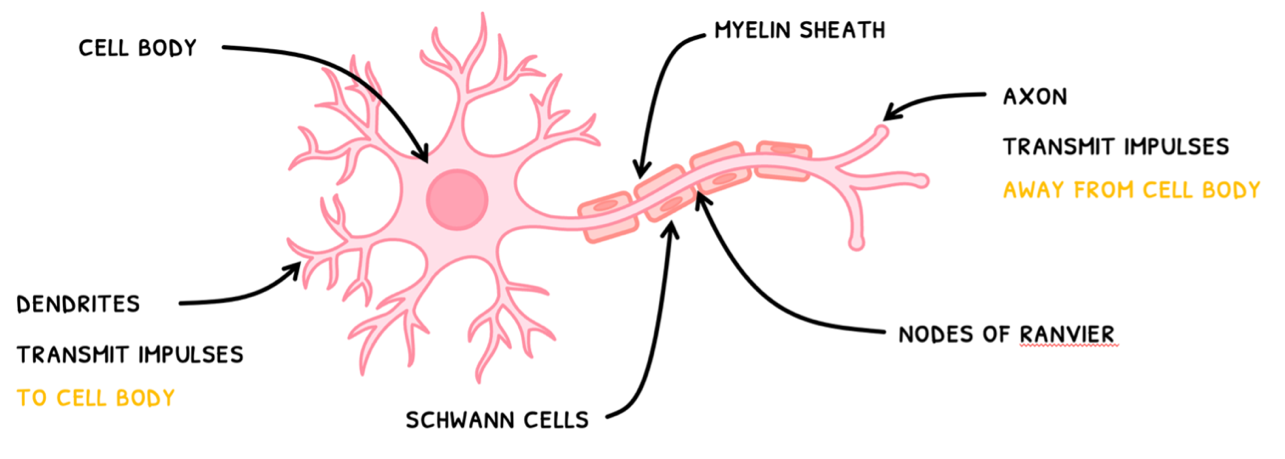

You are expected to know the structure of a neuron well. It is composed of:

- Dendrites - short branched fibers that connect to other neurons and receive their impulses.

- Cell body (soma) - contains a cytoplasm and nucleus and receive all impulses from the dendrites.

- Axon - a long cylindrical 1 μm fiber that transmits the impulses away from the soma to other structures.

Resting potential

This makes neurons extremely adapted to their function, but their axons can be incredibly long. Therefore, it is important to understand how the nerve impulse is generated and propagated.

In IB biology, you use the term action potential instead of nerve impulse. This action potential takes the neuron away from its resting state, called the resting potential.

At resting potential, the inside of an axon is said to be more negative compared to the outside. Numerically, we say it has a resting potential of -70 mV. This voltage is due to three main factors:

- The Na+/K+ pump keeps pumping 3 Na+ out and 2 K+ in, making the outside more positive.

- The axonal membrane is more permeable to K+, allowing it to leave the make the outside more positive.

- Negative proteins inside of the axon make the inside more negative.

Sail through the IB!

C2.2: Further neural signalling (HL)

Action potentials

In the SL syllabus, you learned about neurons and the basics of nerve impulses. However, you need to know how a nerve impulse is generated within a neuron and how it propagates along it.

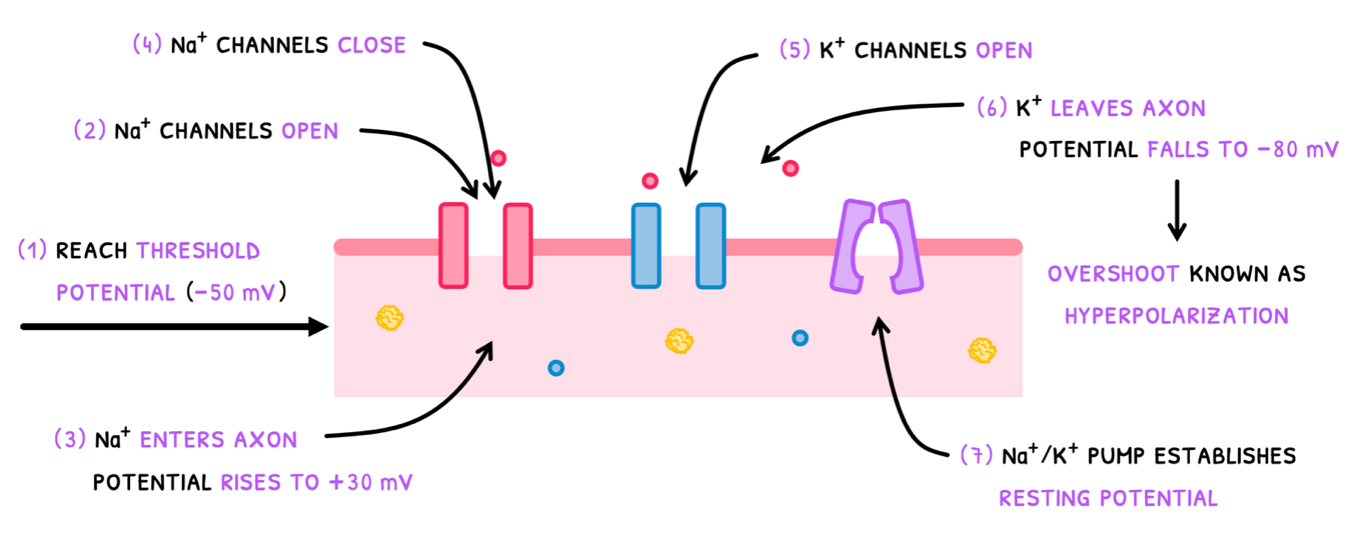

This is called the formation of an action potential, whereby the resting membrane potential of an axon is lost. It is officially defined as the depolarization and repolarization of a neuron due to the movement of ions. Let's explore these terms:

- A positive impulse from a prior portion of the neuron elevates the potential from -70 mV to -50mV, the threshold potential.

- This causes depolarization of the axon, during which voltage-gated Na+ channels are opened to allow the facilitated diffusion of Na+ into the axon.

- This causes the inside of the axon to become more positive, so the potential rises to +30 mV.

- Next, repolarization occurs. First, the Na+ channels close and prevent further entry of sodium.

- Then, voltage-gated K+ channels open to allow the facilitated diffusion of out of the axon.

- This causes the inside of the axon to become more negative, so the membrane potential falls to -80 mV. This overshoot past resting potential is known as hyperpolarization.

- To re-establish resting membrane potential of -70 mV, the Na+/K+ pump exchanges ions back to their original levels.

Local currents

Now that you understand what an action potential is, it is important to understand how it initiates and propagates. This occurs via one of two methods: local currents and synaptic transmission.

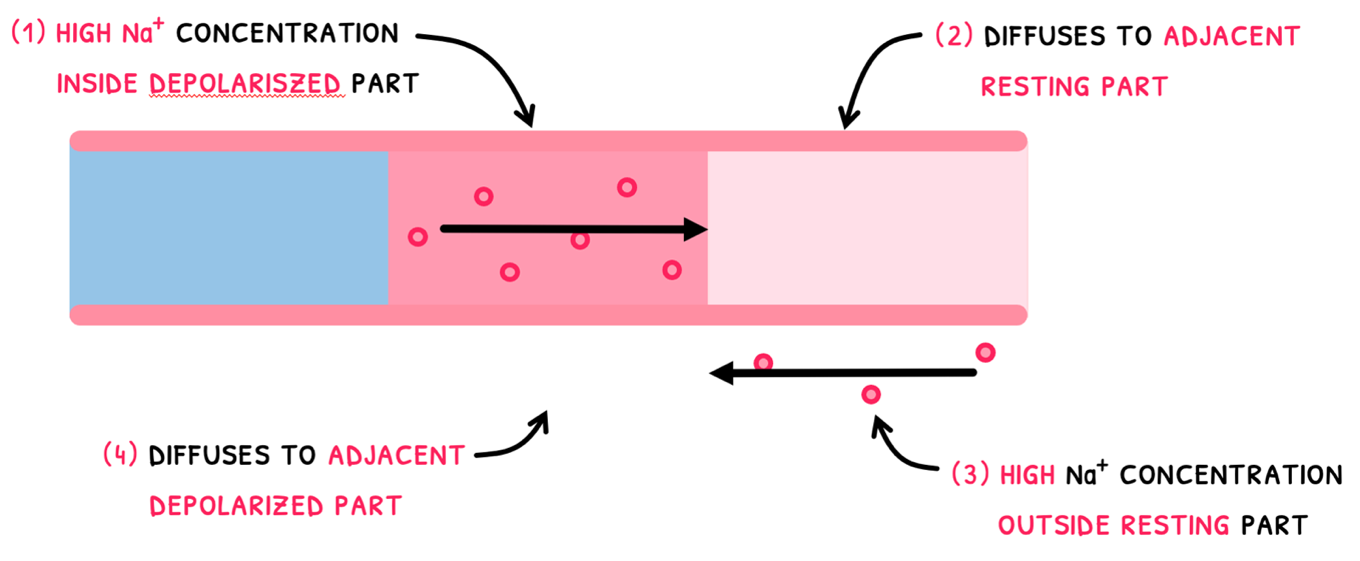

Let's start with local currents. These are positive waves of charge that help adjacent axon parts reach the threshold potential. There are a few elements contributing to this:

- Inside the depolarized area, the Na+ concentration is high.

- Since the next area has a low Na+ concentration, some of it diffuses there, raising its potential.

- Meanwhile, outside the adjacent part there is a high Na+ concentration since it has not depolarized yet.

- Outside the depolarized part, the Na+ concentration is low and thus the ions diffuse to there.

These two movements cause potential of the adjacent part to increase to the threshold potential and initiate the action potential.

However, the action potential does not occur in the previous part of the axon. This is because repolarization of that part means that further action potentials cannot occur for a short period of time, known as the refractory period. This ensures unidirectionality since an action potential must terminate at the opposite end to which it originates.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D2.1: Cell division

Cell division

In this topic, you are expected to know about cell division to produce daughter cells. The division of the nucleus for this occurs one of two ways:

Mitosis - the division of the nucleus into two genetically identical daughter nuclei. This occurs in autosomal cells to produce more autosomal cells.

Meiosis - the division of the nucleus into four genetically distinct daughter nuclei. This occurs to sex cells to produce gametes.

Mitosis

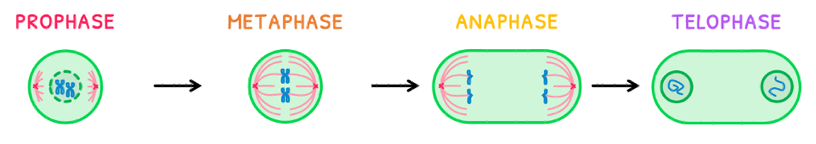

Beginning with mitosis, it is composed of four key stages: prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. You need to describe, in detail, the events that occur in each stage.

- During prophase:

- Chromatin condenses into chromosomes by supercoiling around histones.

- The nuclear membrane breaks down.

- At either pole, centrioles grow a spindle fiber network composed of microtubules.

- During metaphase:

- Spindle fibers attach on both sides to the center of chromosomes, called centromeres.

- The chromosomes are moved to the equator of the cell by microtubule motors and are lined up.

- Proper spindle fiber attachment to each sister chromatid is checked by the cell.

- During anaphase:

- Microtubule motors pull sister chromatids to opposite poles of the cell, separating the cell’s replicated DNA.

- From this point forward, sister chromatids are now chromosomes themselves.

- During telophase:

- Chromosomes reach the poles of the cell and uncoil back into chromatin.

- A nuclear membrane reforms around each chromatin pool, forming the two identical daughter nuclei.

It is very important to stress that mitosis only produces two identical daughter nuclei, whereas cytokinesis divides the cell to form two identical daughter cells. This is a common misconception that will lose you marks if you get it wrong!

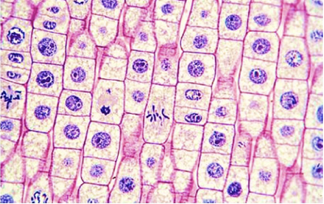

The IB additionally expects you to be able to identify the stages of mitosis on a micrograph. In the micrograph below, we can clearly identify each stage:

From these micrographs, you are additionally expected to calculate a cell’s mitotic index, defined as the percentage of cells undergoing mitosis. In any micrograph, the formula for this is:

mitotic index=total number of cellsnumber of dividing cellsx100%

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D2.1: Cell cycle (HL)

Cell proliferation

Now that you know nearly everything these is to know about cells, you need to understand how cells grow and divide, called cell proliferation. This is an important process in tissues for:

- Tissue growth

- Cell replacement

- Tissue repair

In order to achieve this, cell undergo:

- Stem cells specific to the tissue undergo mitosis to produce two identical daughter cells.

- One of these remains a stem cell and the other differentiates into the specific cell type needed.

- This thus adds new cells to tissue to increase tissue size, replacing lost cells, or both to replace injured/dead tissue.

You are expected to remember three examples of cell proliferation:

- In apical plant meristem, stem cells undergo this process to add new cells to the root or shoot. This is thus cell proliferation for growth.

- In early-stage embryos, stem cells undergo this process to develop and grow tissues and organs over time. This is thus also cell proliferation for growth.

- In the skin, the top layer of cells regularly sheds or gets cut and injured. Thus, stem cells undergo this process to replace lost or dead cells. This is thus cell proliferation for routine cell replacement and wound healing.

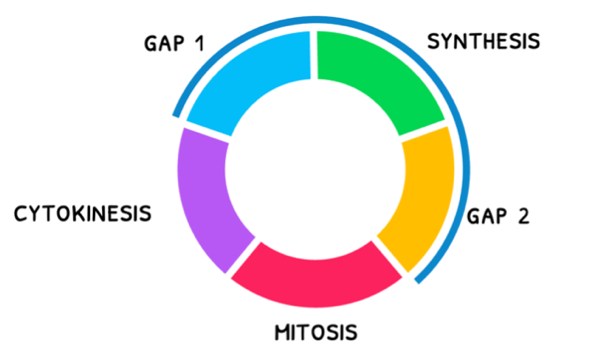

Cell cycle

Continuous cell proliferation is only possible if cells continuously divide. However, their division is only a small part of a repeating sequence of events cells pass through, called the cell cycle.

The cell cycle consists of three main stages:

- Mitosis – this is the stage during which replicated chromosomes are divided to produce two identical daughter nuclei, in preparation for cell division.

- Cytokinesis – this is the stage during which the cell divides in two to produce two identical daughter cells of the same size. Note that in cytokinesis during oogenesis and budding in yeast, this yields two daughter cells of different sizes.

- Interphase – this is the active stage during which the cell spends most of its life and prepares for division. It is composed of four phases:

- Gap 1 – this is the first growth stage of the cell right after mitosis, where proteins are synthesized, and organelles are duplicated to help the cell carry out its function. After Gap 1, the cell can enter either Gap 0 or Synthesis.

- Gap 0 – this is an additional temporary or permanent stage the cell sometimes enters, where the cell does not divide or prepare for division.

- Synthesis – this is the phase wherein the cell undergoes mass organelle and DNA replication to double its chromatin and organelle count.

- Gap 2 – this is the second growth stage of the cell to prepare for mitosis. During this phase, the cell performs a DNA damage check, grows larger, and synthesizes more protein.

Sail through the IB!

D2.2: Gene expression (HL)

Gene expression

This topic focuses on the concept of gene expression. Remember that this is the conversion of genes to proteins to express the gene's coded characteristics. In this, three terms are important to differentiate:

- Genome - the collection of an organism's genes.

- Transcriptome - the collection of an organism's transcribed genes.

- Proteome - the collection of an organisms's proteins.

These may all seem equivalent, but this is not the case. Not all genes are transcribed, and not all proteins are produced from their transcribed genes. Thus, the end phenotype exhibited by a person only matches their proteome, not their transcriptome or genome. The changes from genome to proteome result from changes in gene expression. A person's patterns of gene expression is called their epigenome, whilst the study of epigenomes is called epigenetics.

Nucleosomes

This gene expression is first controlled by nucleosomes, where acetylation, methylation or phosphorylation of the histones can coil or uncoil the nucleosomes.

- Coiling prevents transcription, resulting in decreased gene expression.

- Uncoiling enables transcription, resulting in increased gene expression.

Transcription

The next opportunity to control gene expression is during the initiation of transcription, the process of which we have previously covered. Here, it was discussed that transcription is regulated by promoter sequences, enhancer or repressor proteins, and transcription factors. As a result, whether transcription is initiated or not determines whether a protein is eventually produced.

Once mRNA is produced and released into the cytoplasm, ribosomes can indefinitely translate the strand to produce an infinite number of polypeptides. As this is not desirable, it is prevented by two mechanisms:

- mRNA is stored for translation when it is desired.

- Following translation to the desired output, mRNA is degraded by nuclease enzymes.

This thus regulates gene expression at the last possible moment by controlling the degree to which it occurs.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D2.3: Water potential

Osmolarity

In Topic A1.1, you learned about the properties of water and that it dissolves polar substances via hydrogen bonds or dipole-dipole forces. B2.1, you learned about osmosis and aquaporins. Here, you need to learn about a key practical in biology involving potato cores in different solutions of water and observing the effects of osmosis. However, to effectively understand the practical, a few terms need to be defined first.

- Osmoles – this is the moles of solute particles that are dissolved in a solution.

- Osmolarity – this is a solution’s concentration expressed as the osmoles per liter. Sometimes you may see the term Osmolality, which is osmoles per kilogram, so remember the distinction!

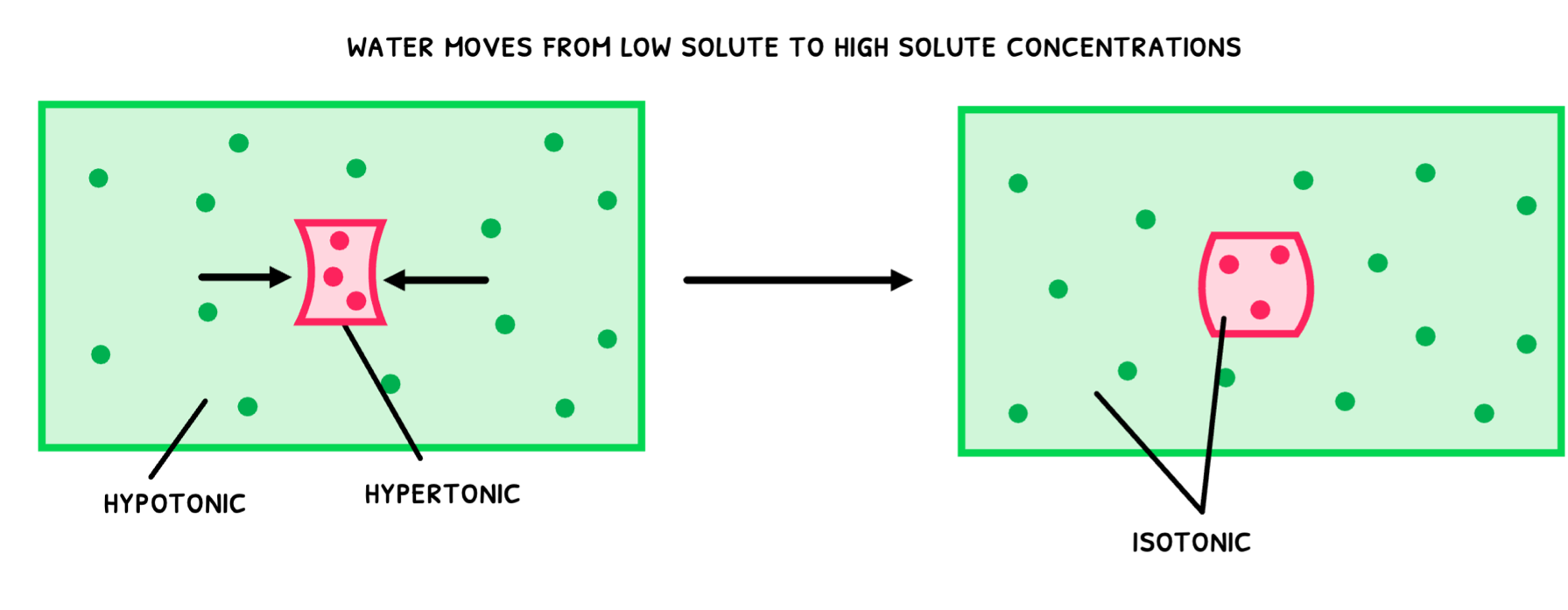

With these definitions, two solutions can be compared using three terms:

- Hypertonic – this refers to a solution with a higher osmolarity than another solution.

- Hypotonic – this refers to a solution with a lower osmolarity than another solution.

- Isotonic – this refers to two solutions with equal osmolarity.

Applying these to the potato, three situations can arise:

- A potato is placed in a hypotonic solution. Remember that this means that the solution’s solute concentration is lower than the potato’s. As a result, water moves from the low solute concentration (the solution) to the high solute concentration (potato) via osmosis. This water movement into the potato causes it to swell.

- A potato is placed in a hypertonic solution. Remember that this means that the solution’s solute concentration is higher than the potato’s. As a result, water moves from the high solute concentration (the potato) to the low solute concentration (the solution) via osmosis. This water movement out of the potato causes it to shrink.

- A potato is placed in an isotonic solution. Remember that this means that the solution’s solute concentration is the same as the potato’s. As a result, water does not move, and the potato does not change in size.

Osmosis in plant cells

Since a potato is a plant, we have a cell wall to consider in these scenarios. It causes a phenomenon called turgidity, which is the pressure exerted on the cell wall. This pressure is also called the turgor pressure and it is important to the structural rigidity of a plant:

- In a normal plant cell, the vacuole is filled with water, exerting turgor pressure on the cell wall. This fills the cell wall and helps it remain rigid, providing structure to the plant.

- If plant cell loses water, its turgor pressure is reduced and eventually lost, causing the plant to wilt. Plasmolysis refers to the complete loss of turgidity in a plant cell and is irreversible.

- If the plant gains more water than normal, its turgor pressure is too high. Normally, this would cause the cell to swell, but this is mostly counteracted by the cell wall, resulting in minor swelling. In this state, the cell is said to be turgid.

Sail through the IB!

D2.3: Further water potential (HL)

Water potential

At this point, you know about water's behavior during osmosis and how it impacts tissues. During this, water molecules are in constant motion and when they collide with the plasma membrane this creates a certain pressure on the membrane, called the water potential (ψ). This is officially defined as the potential energy of water per unit volume, measured in Pascals (Pa).

This potential energy refers to the energy required to transport a unit volume of water to a reference pool of pure free water. It can also be thought of as the tendency of water molecules to enter or exit a solution via osmosis. Note that pure water at standard atmospheric pressure (100 kPa) has a water potential of 0 Pa.

The key thing to remember is that water from areas of high water potential to areas of low water potential. To determine which area is which, we need to look at two factors:

- Solute concentration - defined as the solute potential (ψs).

- Water pressure - defined as the pressure potential (ψp).

These are related to one another via the formula:

ψ=ψs+ψp

Solute potential

Solute potential refers to the impact on water potential by the presence of solutes. Solute potential is always negative, which can be explained through various scenarios:

- Pure free water requires no energy to extract. Thus, its water potential is zero.

- A low concentration solution requires a little energy to extract water from the solutes. Thus, its water potential is slightly negative.

- A high concentration solution requires a lot of energy to extract water from the solutes. Thus, its water potential is very negative.

As you can see, the presence of solutes always requires energy to remove, resulting in a negative contribution to water potential. Additionally, osmosis can now be redefined according to water potential. Water moves from a low solute concentration to a high solute concentration can be restated as water moves from a high water potential to a low water potential!