IB Biology Topic 3 Notes

A3.1: Diversity of organisms

Species

Topic 3 focuses on organisms, and you are supposed to understand that every individual organism is unique in some capacity and that not all their traits are identical due to genetic variation. However, organisms can be grouped together via shared traits for successful classification. At the most specific level of classification, organisms are classified as species. The biological definition of a species is a group of organisms that can interbreed and produce fertile offspring.

However, this definition does not work in several situations:

- Asexual reproduction in prokaryotes and some eukaryotes does not involve interbreeding.

- Extinct groups of organisms that look morphologically similar, but it is not known if they can interbreed.

- Morphologically different organisms that are listed as separate species but can interbreed to form hybrid fertile offspring.

- When populations form a geographical ring, where adjacent populations can interbreed but populations further away from each other cannot.

As a result of these issues, there are other definitions (concepts) of species that explain different aspects of species:

- Agamospecies - differentiates between asexual species based on morphology or cytology.

- Biospecies - differentiates between species based on reproductive isolation.

- Ecospecies - differentiates between species based on their ecological role (niche).

- Evolutionary species - differentiates between species based on their evolutionary line.

- Genetic species - differentiates between species based on their gene pools.

- Morphospecies - differentiates between species based on their phenotype.

- Taxonomic species - differentiates between species based on their taxonomy.

Binomial naming

Since there are millions of different species globally, they need to be named. This is done by the binomial naming system, initially developed by Carl Linnaeus in his books on the known species of plants and animals in 1753 and 1758, respectively. In an annual International Botanical Congress meeting in the late 19th century, this method of naming was agreed to be the standard method of naming organisms.

The binomial naming method, as the name suggests, names species via two words: its species and its genus. For correct notation, three rules apply:

- Genus is capitalized but species is not.

- The entire name is written in italics.

- The genus name can be abbreviated to the first letter.

For example, humans would be named Homo sapien or H.sapien, whereas the grey wolf would be Canis lupis or C.lupis.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

A3.1: Further diversity (HL)

Biological Species Concept

Whilst you learned about the biological species concept in the SL syllabus, you need to be aware of its limitations in the HL syllabus. The concept works well in the case of sexually reproducing species because they satisfy the criterion of being a group of interbreeding organisms that are reproductively isolated.

However, species that reproduce asexually, such as bacteria via binary fission and yeast via budding do not fit this concept well. This is for several reasons:

- They do not have reproductive barriers that apply to the definition.

- The genetic uniformity in offspring produced by asexual reproduction greatly limits variation. This makes it impossible to distinguish a species based only on genetic differences.

- Asexually produced organisms often evolve rapidly. They are also readily subject to adaptations; this makes delineating species boundaries challenging.

- Bacteria transfer genes via horizontal transfer as opposed to vertical transfer like other organisms. This removes barriers to reproductive isolation as each bacteria does not undergo evolution by reproduction

- Lastly, species hybridize. This is common in plants and many significant crops such as wheat and potatoes, or ducks such as the Mallard duck. This presents the problem of species overlap as these hybrids easily breed with other species.

Thus, it can be seen that reproductive isolation and evolution are not independent and delineated processes in these organisms, presenting issues. However, the difficulty of the biological species concept also applies to extinct species and those species for which available data is limited. This is because interbreeding populations are not possible amongst extinct species. Thus classification becomes more difficult.

Chromosome number

However, some lines can be drawn. For example, groups of species can definitively be determined by chromosome number. The chromosome number is a shared trait within a species with each species having a specific number and characteristics. This permits haploid (n) gametes to fuse to form a diploid zygote (2n).

Since chromosomes thus need to pair up in a cell, each species needs the same number of chromosomes. If species interbreed, it results in an unequal number of chromosomes and thus some chromosomes are not paired up. This often means that the resulting zygote does not properly develop and grow, resulting in a miscarriage. However, sometimes species with different chromosome numbers manage to produce offspring, but these offspring are sterile. For example, the offspring of a horse and donkey is a sterile mule.

However, chromosome numbers are not readily visible in some species. Species are thus typically easily identified via their characteristics with a dichotomous key.

Sail through the IB!

A3.2: Classification & cladistics (HL)

Classification

You previously learned about species and the binomial naming system. However, the binomial naming system is only a subpart of a whole system of organism classification. Taxonomy is the study of classifying organisms, which has resulted in this classification system.

It groups organisms with shared ancestors together in tiers called taxa, of which there are eight main ones you need to know:

- Domain

- Kingdom

- Phylum

- Class

- Order

- Family

- Genus

- Species

The sequence of taxa can easily be remembered with the mnemonic Dumb King Phillip Came Over For Good Spaghetti.

As you go down the taxa, they become more specific. Each subsequent taxa will contain fewer species with an increasing number of similar traits.

Cladistics

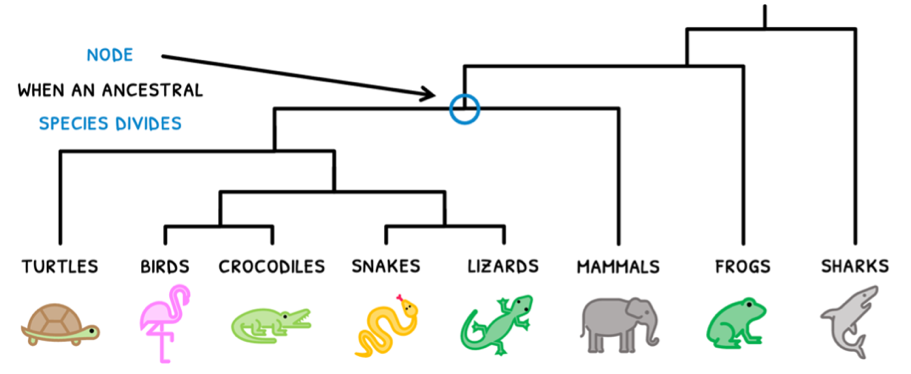

However, since evolution is gradual, having fixed ranks means that the patterns of divergence do not always correspond to the classification. An alternative approach to this is cladistics. In cladistics, groups of organisms with a common ancestor are termed clades. They are thus like taxa, but can be applied for any group of organisms, small or large.

Cladistics was historically based off morphology, and thus an example of artificial classification, but is now based off amino acid sequence, making it highly accurate.

In cladistics, visual diagrams can be made to present the relationship between different organisms and where they had a common ancestor. These visual diagrams are known as cladograms.

In a cladogram are branching points, termed nodes, which signify when an ancestral species divides to form two or more species. Cladograms display the most likely hypothetical path of evolution, based on the smallest number of changes possible, known as the principle of parsimony.

Sail through the IB!

B3.1: Gas exchanges

Gas exchange

Next, you are expected to learn about gas exchange, which is the process by which organisms transfer oxygen and carbon dioxide for respiration or photosynthesis. This is evidently a vital processes in all organisms for them to live. However, as organisms become larger, the SA:V ratio obviously becomes smaller and the distance from the surface to the innermost cells increases.

As a result, multicellular organisms have developed systems for efficient gas exchange, called gas-exchange surfaces.

Most gas exchange surfaces have several properties that make them adapted to perform gas exchange:

- Thin tissue layer - this allows for a short diffusion distance, resulting in rapid diffusion of gases.

- Permeable tissue - allows for diffusion of gases to occur.

- Moist environment - allows for gases to dissolve in the surrounding environment and be present at high concentrations.

- Large surface area - maximises the amount of gas exchange that can occur across the layer.

To facilitate one-way gas exchange, these surfaces also need to maintain concentration gradients. This is often performed by:

- A dense network of blood vessels - these make sure that gas exchange area is maximised and that plenty of CO2 rich and O2 poor blood reaches the surface to maintain the concentration gradient.

- Continuous blood flow - blood flow at the right speed maintains a high internal CO2 concentration that diffuses out and low internal O2 concentration that drive diffusion across the entire length of the surface.

- Ventilation - whether with air in the lungs or water in the gills, a continuous exhalation of carbon dioxide rich air and inhalation of oxygen rich air maintains the concentration gradients needed to keep gases diffusing in the right direction.

Mammalian respiratory system

However, gas exchange surfaces are differently organized in mammals and plants. You are expected to know it in both organisms, starting in mammals. Mammals have a respiratory system wherein gas exchange occurs with the circulatory system to bring in oxygen and take out carbon dioxide

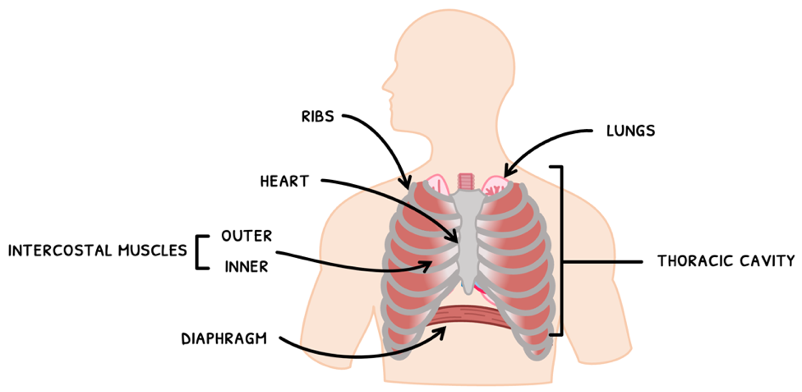

This begins by understanding the anatomy of the respiratory system. The lungs are large air-filled organs in our thoracic cavity, surrounded by:

- The diaphragm - a curved muscle below the lungs.

- The heart - nestled between the lungs.

- The ribs - which a form a cage to protect the lungs from trauma.

- Intercostal muscles - between the ribs, separated into an inner and outer layer.

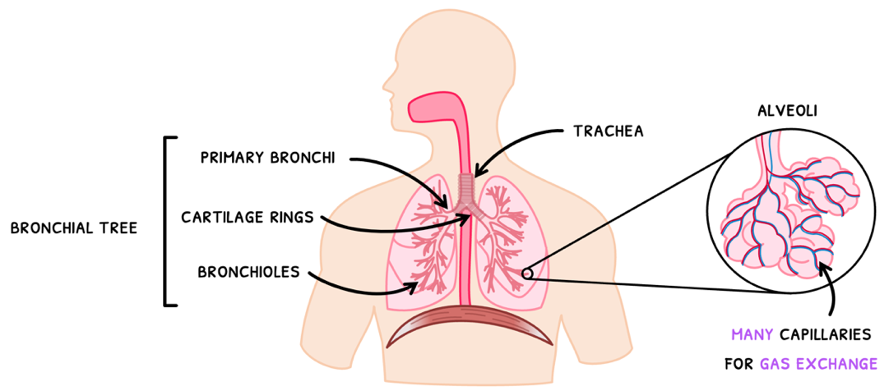

Internally, the important structures of the lungs include:

- The trachea - the tube connecting the lungs to the mouth, with cartilage rings to keep them open.

- Primary bronchi - the first division of the trachea into both lungs.

- Bronchioles - the many tubes that branch from the bronchi into the lungs.

- Alveoli - sac-like structures at the end of bronchioles that perform gas exchange.

- Capillaries - surround the alveoli to enable gas exchange in and out of the blood.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B3.1: Further gas exchange (HL)

Haemoglobin

In the HL syllabus, you are expected to learn more about gas exchange - specifically how oxygen is transported around the body once it has diffused into the bloodstream. This is typically performed by haemoglobin, which is found in the red blood cells of adults. Its structure is two α peptides and two β peptides each with a haem group.

The Iron ion in the haem group is what permits red blood cells to carry, transport, and release oxygen around the body. However, the amount of oxygen carried depends on the oxygen pressure in the blood. As oxygen pressure increases, the amount of oxygen carried by haemoglobin increases.

This can be shown by an oxygen dissociation curve, which produces an S-shape. You are expected to know why the curve is shaped like this:

- When O2 binds to the haem group of a subunit, it results in a structural change to the haemoglobin, called allostery.

- It increases the affinity of other subunits for O2, increasing the amount of oxygen binding, referred to as cooperative binding.

As a result, oxygen can quickly be picked up during gas exchange in the lungs. However, at the cells, the oxygen must be released. Here:

- High CO2 levels cause a decrease in blood pH, increasing acidity.

- When an H+ ion or a CO2 molecule binds to a subunit of haemoglobin, its affinity for O2 decreases.

- Thus, oxygen is released from the other subunits to allow it to diffuse out of the blood and into the cells.

Bohr shift

This change in oxygen dissociation as a result of changing pH levels is called the Bohr shift. It refers to the phenomenon that red blood cells adapt their binding affinity depending on the surrounding environment. This is typically dependent on carbon dioxide levels (pCO2), pH, and temperature.

- If pCO2 is low, pH is high, or temperature is low, there is an increased affinity for oxygen. This means that more oxygen is bound at the same pressure, causing the dissociation curve to shift left.

- If pCO2 is high, pH is low, or temperature is high, there is a decreased affinity for oxygen. This means that less oxygen is bound at the same pressure, causing the dissociation curve to shift right.

Sail through the IB!

B3.2: Transport

Circulatory system

Remember from Topic B2.3 that the surface area-to-volume ratio limits cell size due to supply and waste removal restrictions. To circumvent this issue, organisms use a transport system to provide cells with oxygen and glucose for metabolism, while taking away metabolic waste products.

You need to be aware of this transport system in mammals and plants, primarily focusing on their vasculature.

Human vasculature

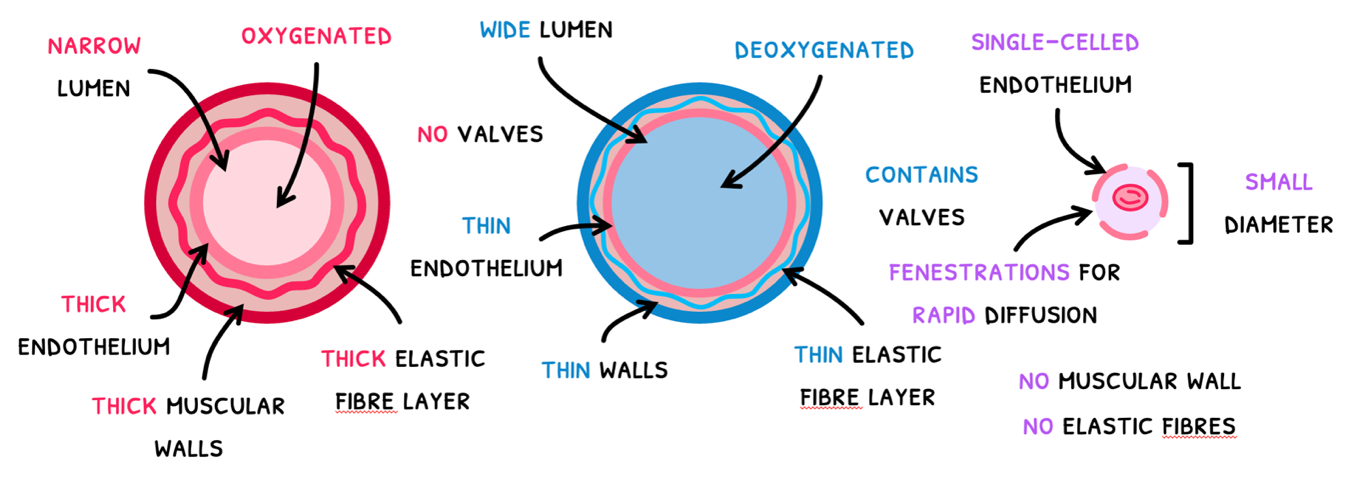

In humans, this transport system is the circulatory system – centered around a heart pumping blood through a series of vessels. You are expected to know the structure of these vessels. As you likely know, there are three types of vessels:

- Arteries – vessels that carry high pressure blood away from the heart. To withstand and maintain these high pressures, they possess a narrow lumen and thick layers.

- Veins – vessels that carry low pressure blood to the heart. To maintain blood blow at these low pressures, they possess a wide lumen and thin layers with valves to prevent backflow.

- Capillaries – small vessels that connect arteries to veins and transport blood to individual cells. To allow substances to easily diffuse in and out, they have a thin endothelium with fenestrations.

Although arteries typically carry oxygenated blood and veins carry deoxygenated blood, remember that this is not always the case due to the double circulatory system.

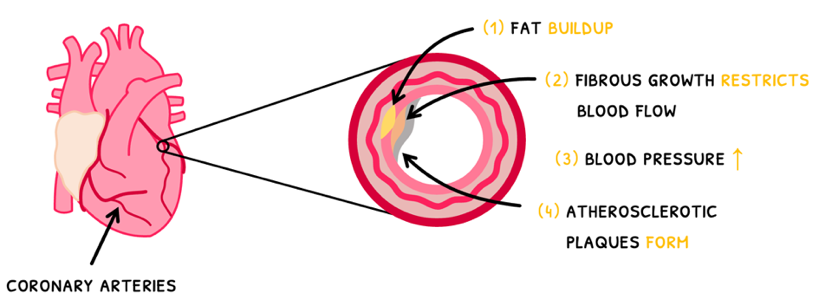

Coronary occlusion

There are several issues which could cause blood flow in vessels to stop. One of those issues is coronary heart disease, which can lead to coronary occlusions. The process by which this occurs is:

- Excess cholesterol and lipids in the blood lead to fat build-up under the endothelium.

- This damages the vessel and causes fibrous tissue to grow to protect the vessel.

- This growth ends up decreasing the size of the lumen, restricting blood flow and increasing blood pressure.

- This causes further damage and fibrosis, forming atherosclerotic plaques.

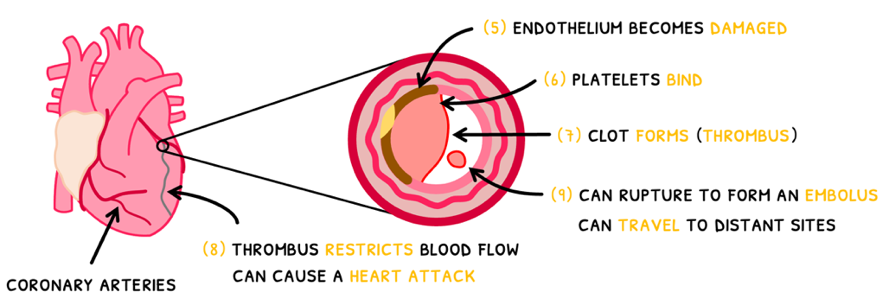

- Over time, blood flow can cause the plaque to come loose and rupture. This can happen in two ways.

- The resulting damage to the endothelium can trigger the recruitment of platelets.

- This trigger the clotting cascade and result in the formation of a clot, called a thrombus. You will learn the details of clotting in Topic 6.3.

- If the plaque completely comes loose, it is called an embolus, which is typically small enough that it travels to smaller vessels.

- Both scenarios involve the formation of a solid that can then get stuck in a downstream coronary artery and restrict blood flow to cardiac tissue. This prevents the tissue from getting oxygen and it begins to die, causing a heart attack.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B3.2: Further transport (HL)

Tissue fluid

In the SL syllabus, you learned the basics of blood vessels and cardiovascular disease. However, in the HL syllabus you are expected to know much more detail about blood flow in capillaries, the circulatory system, and the heart. Let's start with capillary networks, which provide an efficient distribution route for delivery of blood. Each capillary exchanges fluid with adjacent tissue to supply cells with fresh oxygen and nutrients and drive out carbon dioxide and waste. However, it is the tissue fluid that circulates between capillaries and cells that delivers these substances directly to and from the cell membranes.

To perform this, tissue fluid is subjected to a number of pressure and concentration gradients. At the arteriolar end of a capillary bed:

- Arriving plasma is high in oxygen, glucose, and amino acids and low in carbon dioxide.

- High hydrostatic pressure forces fluid out of the capillary and into the tissue fluid.

- The solute concentration of this tissue fluid is high since it is rich in water, mineral ions, glucose, amino acids and oxygen. It has a similar composition to plasma, without blood cells.

- This fluid bathes the cells of the tissues to supply them with the necessary nutrients.

At the venous end:

- The blood vessel has a reduced hydrostatic pressure and solute concentration due to movement into the tissue at the arteriolar end.

- Here, water, CO2 and waste products that have been exported out of cells are reabsorbed into the bloodstream. The returning is thus low in oxygen, glucose, and amino acids, and high in carbon dioxide and waste.

The returning plasma fluid accounts for 90% of the original leaked fluid. The remaining 10% is collected by the lymph vessels and returned to the circulation near the heart. Let's cover how this occurs.

Lymph fluid

The primary role of the lymphatic system is to transport lymphocytes around the body. They just have a network of lymph vessels equally extensive as the circulatory system. However, they require a fluid circulation for transport to occur.

Thus, lymph capillaries are found between cells where they are held in place by collagen filaments attached to connective tissue. Tissue fluid that leaks from the blood vessels moves into lymph capillaries through gaps between thin cells, forming lymph fluid. As a result, lymph fluid has a similar composition to tissue fluid but contains lymphocytes due to its role in the immune system.

The lymph capillaries merge first into pre-collector and then collector lymphatic vessels. These vessels possess valves to ensure unidirectional flow to the lymph nodes, where the lymph fluid collects from all over the body. This forms a network of tissues, organs and vessels that accumulates tissue fluid that has leaked out of blood vessels. This is finally drained into the subclavian vein to return to the heart.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B3.3: Muscle & motility (HL)

Locomotion

So far you have learned about the transport and respiratory systems of organisms for them to live. Next, you need to know about their locomotion (movement), which begins with understanding the two types of species in this context:

- Sessile species - species that are fixed in one place. As a result, they respond to their environment by changing their growth or development. An example is the phototropism of plants.

- Motile species - species that are able to move around. As a result, they respond to their environment by changing their position. An example is the movement of crocodiles into the light to raise their body temperature.

Most sessile species evolved before muscles developed and therefore do not contain muscle. However, many organisms on the plant do contain muscle, and you need to know more detail about how muscles and related structures contribute to the movement of motile species.

However, movement is still very important as it is required to forage for food, escape from danger, search for a mate, and migrate at the least. Examples for each are expected but should be easy to mention from experience (a duck will perform all four).

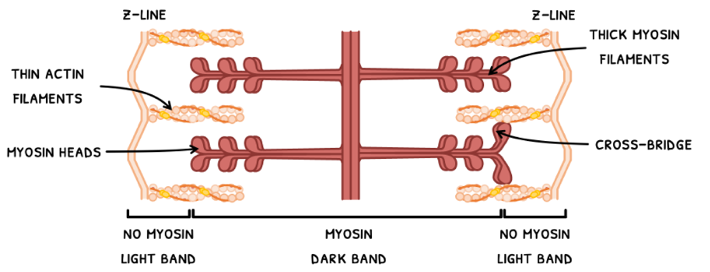

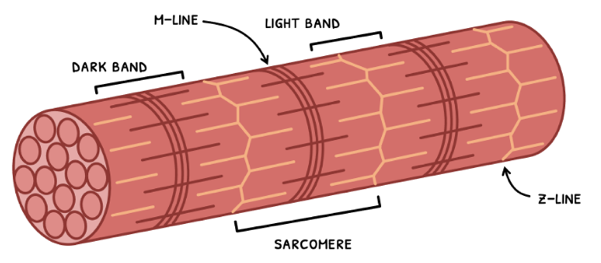

Sarcomeres

Each myofibril is composed of many end-to-end units called sarcomeres. These are defined as the smallest functional unit of skeletal muscle. You are expected to know its structure in detail. Each sarcomere is composed of:

- Z-line – the anchoring outer protein filaments between which the sarcomere lies.

- M-line – the anchoring protein filament in the middle of the sarcomere.

- Actin filaments – thin twisted protein filaments attached at one end to a Z-line.

- Myosin filaments – thick protein filaments attached to an M-line. Each myosin filament contains many heads that bind to myosin binding sites on the actin filaments, forming cross-bridges.

- Tropomyosin – a fibrinous protein on actin filaments that blocks myosin binding sites.

- Troponin – a globular protein on actin filaments that moves tropomyosin to block or unblock myosin binding sites.

- Titin - a fibrous protein that connects myosin filaments to the Z-line. Titin prevents overstretching of the sarcomere and recoils the sarcomere to base position after stretching.

The structure of a sarcomere gives skeletal muscle its characteristics striated banding pattern. Let’s look at the elements of this pattern:

- The dark band – this is the section of the sarcomere where there are myosin filaments. Their density and any overlap with actin filaments give this section a distinctive dark color.

- The light band – this is the section of the sarcomere where there are only actin filaments. Due to the lack of myosin and low density of actin filaments, this section is noticeably lighter in color.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C3.1: Body systems

Biological systems

This topic primarily focuses on the integration of biological systems into the body to coordinate different actions. The hierarchy of organization to perform this is:

- Atoms and molecules comprise the chemical level.

- Organelles and structural components of cells comprise the organelle level.

- Cells the basic subunits of living organism comprise the cellular level.

- Groups of cells form tissues, comprising the tissue level.

- Two or more tissue type come together to form organs, comprising the organ level.

- Finally, the organism is composed of multiple cooperating organ systems that forms the organism.

Successful integration of these body systems leads to emergent properties that could otherwise not be exhibited at individual levels. However, for an organism to function well, it must coordinate multiple processes at multiple levels.

For example, the cardiovascular system is a body system that must integrate with all the other body’s systems to permit life processes to occur:

- Organs including the heart and the vasculature must integrate in function to permit efficient transport of substances around the body at the correct pressure.

- The tissue level must also integrate to permit the cardiac muscles to contract as needed.

- At the cellular level adequate levels of glucose and oxygen must be provided to enable the mitochondria to generate the ATP needed by the muscle fibres.

However, the heart must be connected to other organs in order to respond appropriately to different events occurring around the body. Cue signalling.

Signalling

Effective communication between cells, tissues and organs and ensure effective integration of organs around the body. The two key signalling systems that undertake this are the endocrine system and the nervous system. They work together and independently to maintain homeostasis in the body in different ways, nature, and durations.

- The nervous system communicates via electrical impulses that are rapid but also short lived. Nervous signalling is typically used when rapid responses are required, such as reflexes.

- The endocrine system relies on the secretion of hormones into the blood to elicit a response at target tissues. This takes much longer and often has a prolonged response, although hormonal communication can still be fast such as when adrenaline secretion evokes the ‘fight or flight’ response.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C3.1: Plant systems (HL)

Plant growth

You previously learned how water and solutes move through xylem and phloem. The circulation of these is incredibly important to sustain plant cell metabolism and growth, especially because they endlessly grow.

Whilst human cells continually undergo mitosis to growth this stops sometime after puberty. After this, stem cells divide by mitosis to replace cells that have died or been sloughed off. Therefore, humans have a definite size limit and thus undergo determinate growth.

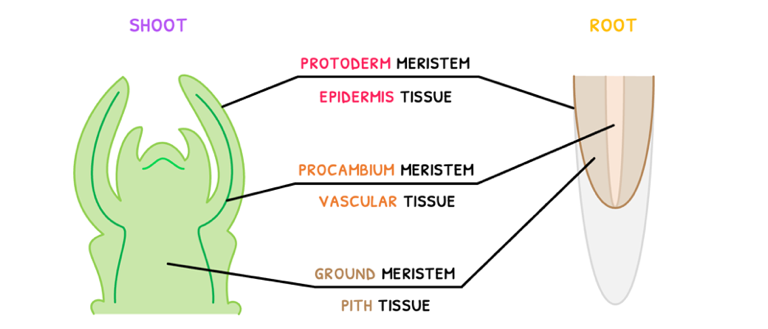

On the other hand, plant cells carefully organize their cells so that some remain pluripotent stem cells and can continue to grow the stems and roots out. Therefore, plants have an indefinite size limit and thus undergo indeterminate growth.

The structures in plants responsible for this are called apical meristems, found in the tips of stems and roots. During one mitotic division, one pluripotent stem cell remains whilst the other differentiates and migrates to its tissue. This organization allows plants to retain their puripotency in the meristem.

There are three types of meristem in plants that form different tissues:

- Protoderm meristem - this forms epidermal tissue.

- Procambium meristem - this forms vascular tissue

- Ground meristem - this forms pith issue.

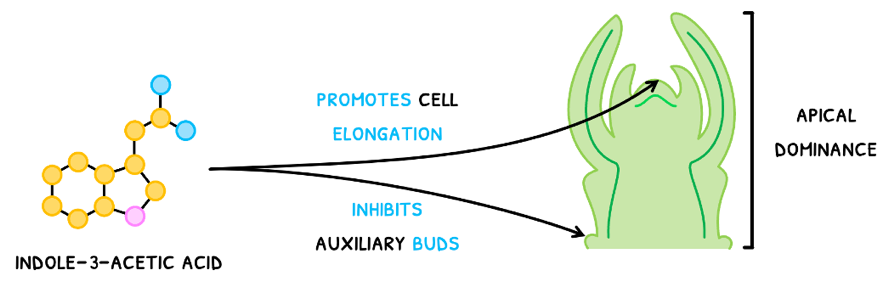

Auxins

However, plants do not grow uncontrolled. Their division by several hormones, the most of important of which is auxin. Auxin controls growth, leaf development, and flower formation. The most prevalent one is indole-3-acetic acid, which functions to:

- Promote cell elongation in the apical meristem.

- Inhibit residual stem cells found in auxiliary buds.

This acts to promote vertical growth of stems but prevent the growth of leaves, called apical dominance. In roots, cytokinins are the more active hormone.

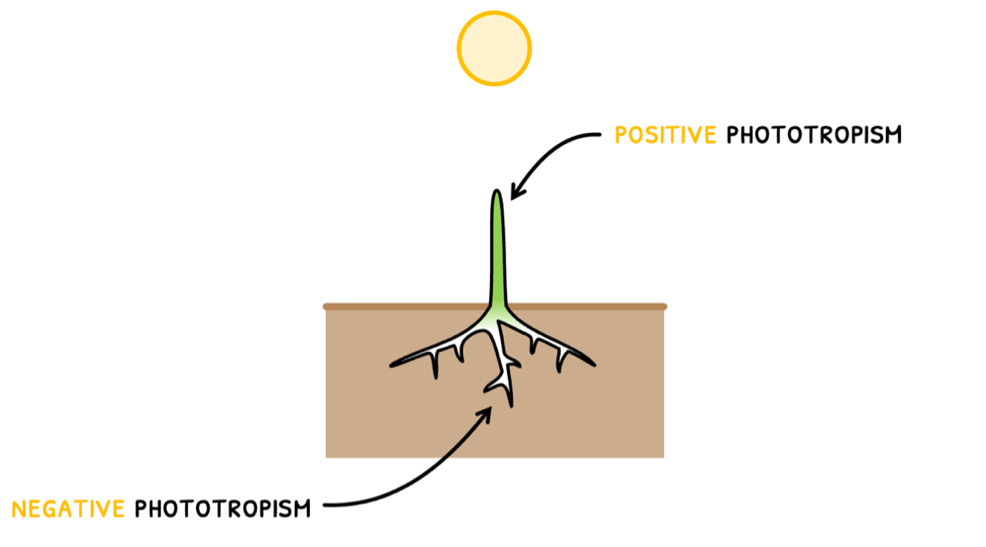

Phototropism

The regulation of shoot and root growth primarily occurs in response to external factors, a phenomenon called a tropism. You are expected to know about phototropism, plant growth in response to light. There are two types of phototropism:

- Positive phototropism - the growth of shoots towards light.

- Negative phototropism - the growth of roots away from light.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C3.2: Defence against infectious disease

Immune system

Whilst you will learn about normal body function and how it fails during conditions, it is also important to understand how the body handles infectious disease. Organisms or viruses that cause infectious disease are called pathogens. The is the job of the immune system is to prevent pathogens from causing a disease, which is divided into:

- Primary defense system – structures that aim to prevent pathogen entry.

- Secondary defense system – structures that aim to destroy pathogens that have bypassed the primary defense system.

Primary defense system

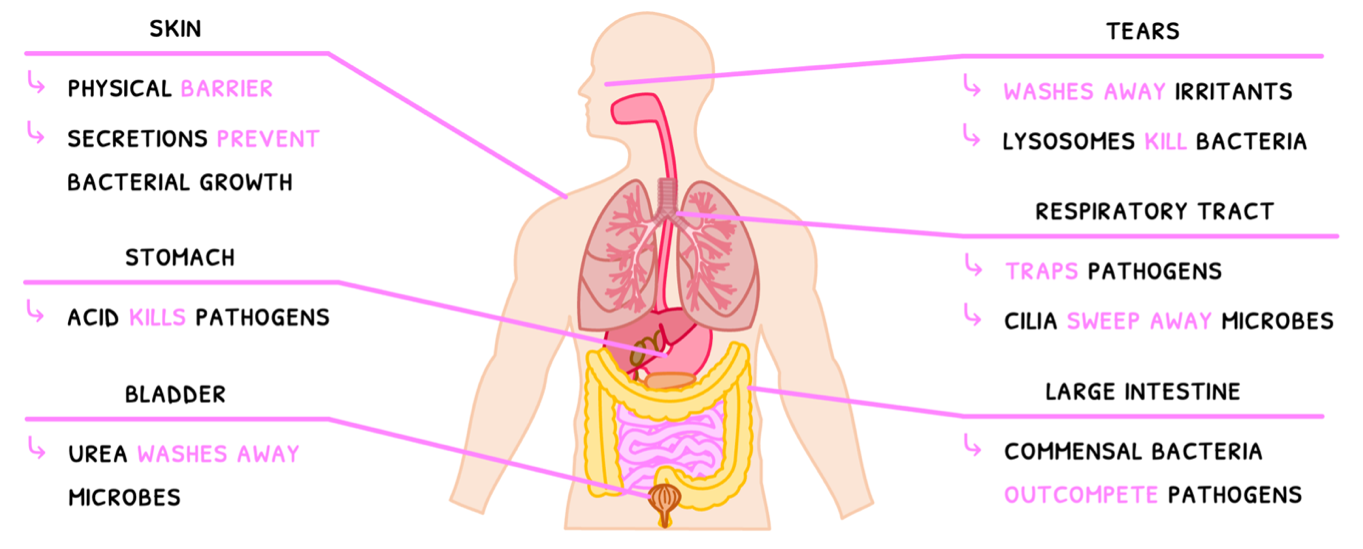

Let’s start with the primary defense system. The structures that contribute to the prevention of pathogen entry include:

- The skin is a thick outer layer that forms a physical barrier against pathogen entry. It contains sebaceous glands that secrete lactic acid and fatty acids to prevent bacterial growth.

- Tears wash away irritants and microbes and contain lysosomes to kill bacteria.

- The respiratory tract and nose have a moist mucous membrane which traps pathogens and contains lysosomes. The membrane also contains cilia, which are hair-like extensions on cells that move mucus out of the tract.

- The stomach contains hydrochloric acid to kill pathogens.

- The large intestine contains native bacteria, called commensal bacteria, that outcompete pathogenic bacteria.

- The bladder contains urea and washes away microbes trying to enter the urethra.

Clotting

However, these structures are not flawless. For example, the skin can be cut or tear, requiring a set of reactions to seal this point of entry. This is facilitated by a set of chemical reactions that result in the formation of a clot.

- A cut or tear to the skin typically damages blood vessels, exposing collagen fibers.

- The collagen fibers communicate damage, recruiting platelets within the blood.

- The platelets then release chemicals, known as clotting factors, to initiate the clotting cascade.

- The clotting factors also recruit further platelets to the tear to form an emergency barrier and prevent further blood loss.

- You do not need to know all the chemicals involved in the clotting cascade. However, you need to know that it occurs while more platelets are being recruited. At the end of the cascade, a few key reactions occur.

- Thromboplastin becomes activated, which catalyze the conversion of prothrombin into thrombin.

- Thrombin then converts inactive soluble fibrinogen into its active and insoluble form, known as fibrin.

- Fibrin is a filamentous protein, and its insolubility means that it sticks to the platelets and forms a mesh over the tear, forming a clot.

- This clot further prevents blood loss and dries to form a scab, preventing pathogen entry.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D3.1: Reproduction

Reproduction

In Topic D3.1, you learn about reproduction. Remember that this is the production of offspring by parents and that this can occur in two ways:

- Asexual reproduction - a parent organism independently produces genetically identical offspring. This can only occur when the parent is adapted to the environment, or the offspring will not survive.

- Sexual reproduction - two parent organisms produces gametes and bring them together during fertilization. This produces offspring with genetic variation as they need adaptation to a changing environment.

Within sexual reproduction, males and females have different reproductive strategies:

- Males are involved in physical or sperm competition with one another to have the chance to reproduce with a female.

- Females are thus in a position of power and strategize to obtain resources from males or the best male genes for their offspring.

Reproductive anatomy

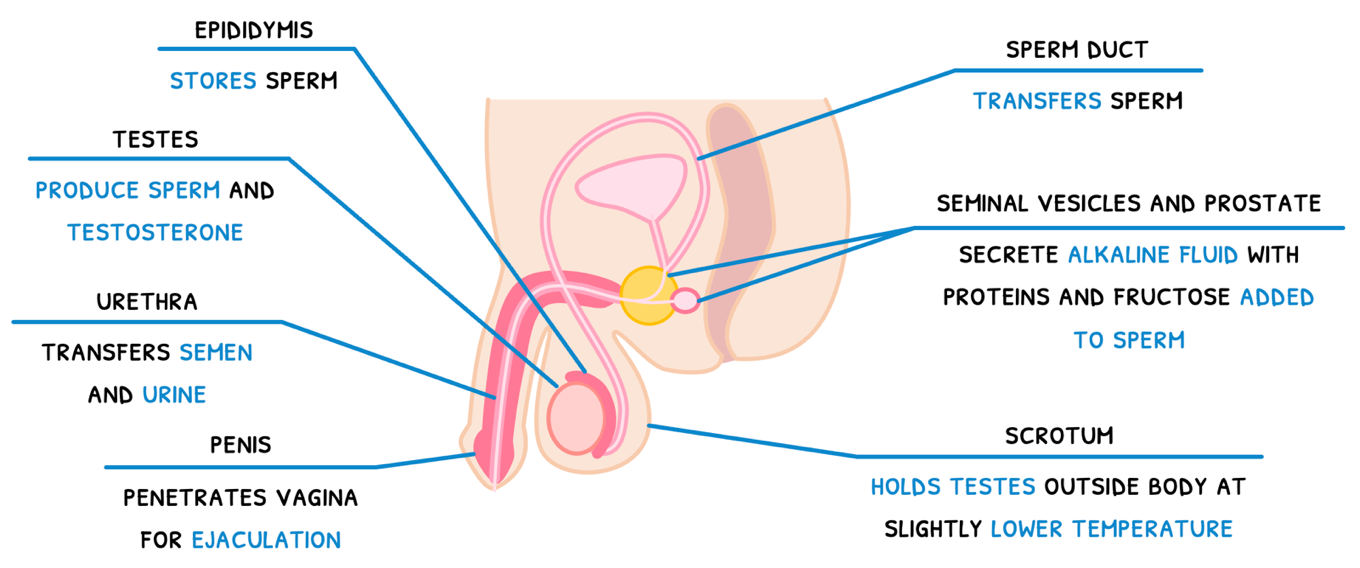

Now that you know the basics of fertilization, you are expected to identify and outline the function of the reproductive structures in males and females.

Starting with males, their reproductive structures include:

- The testes - egg-shaped structures that produce sperm and testosterone.

- The epididymis - a structure located atop each teste, which stores sperm.

- The scrotum - a sac that holds the testes outside the body, at a temperature slightly lower than core body temperature.

- The sperm duct - a tube which transfers sperm.

- The seminal vesicle and prostate gland - structures which secrete an alkaline fluid containing proteins and fructose which are added to sperm to make semen.

- The urethra - a tube that transfers semen and urine.

- The penis - a muscular structure that penetrates the vagina for ejaculation near cervix.

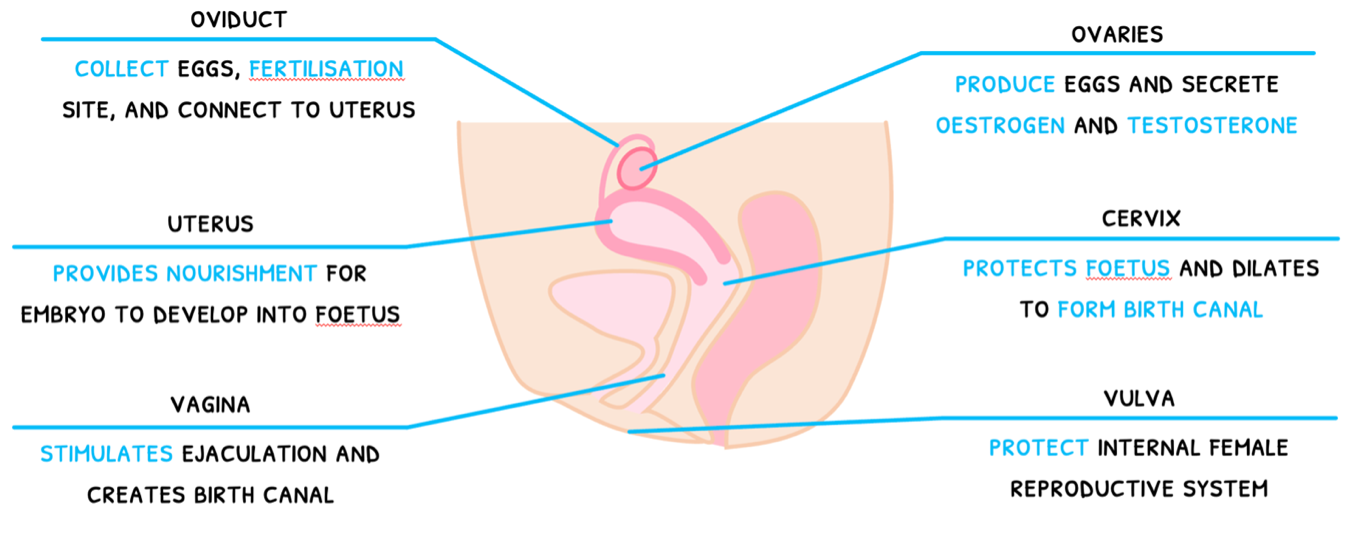

The female reproductive system contains:

- The ovaries - egg shaped structures that produce eggs and secrete oestrogen, and progesterone.

- The oviducts - tubes which collect eggs, provide a fertilisation site and transfer the embryo to the uterus.

- The uterus - a structure which provides nutrients and hormones for the embryo to develop to form a foetus. The lining of the uterus is known as the endometrium.

- The cervix - a structure which protects the foetus and dilates to create the birth canal.

- The vagina - a structure which stimulates ejaculation and creates the birth canal.

- The vulva - structures which protect the internal female reproductive system.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D3.1: Further reproduction (HL)

Puberty

You previously learned that every human at birth is either biologically male (XY) or female (XX), characterised by distinct anatomy known as the primary sexual characteristics. The combination of genetic and chemical changes that influence this outcome are collectively termed sex determination. Beyond this, when puberty is reached, there are further anatomical changes known as secondary sexual characteristics.

In males:

- The SRY gene on the Y chromosome codes for DNA binding protein TDF.

- TDF stimulates the embryonic glands to develop into testes.

- The testes secrete the hormone testosterone in weeks 8-15 of pregnancy, stimulating the development of male primary sexual characteristics: the presence of a male reproductive system.

- During childhood, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is increasingly released by the hypothalamus.

- This causes an increase in LH and FSH levels throughout childhood.

- Eventually, this initiates puberty by increasing testosterone levels rise and cause the development of male secondary sexual characteristics, including:

- Sperm production

- Penis enlargement

- Growth of pubic hair

- Voice deepening

In females:

- The lack of the SRY gene due to the absence of a Y chromosome does not stimulate TDF.

- This causes the embryonic glands to develop into the ovaries and placenta.

- The ovarie secrete the hormones estrogen and progesterone in weeks 8-15 of pregnancy, stimulating the development of female primary sexual characteristics: the presence of a female reproductive system.

- During childhood, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is increasingly released by the hypothalamus.

- This causes an increase in LH and FSH levels throughout childhood.

- Eventually, this initiates puberty by increasing estrogen and progesterone levels and cause the development of female secondary sexual characteristics, including:

- Menstruation

- Breast enlargement

- Growth of pubic hair

Gametogenesis

Once puberty is initiated, the reproductive cycles come into full swing. To completely understand the systems, you need to learn how gametes are produced, how they come together during fertilization, and how the resulting zygote develops into an embryo, fetus, and is then born. The starting point for all these processes is the production of gametes, called gametogenesis.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D3.2: Monogenic inheritance

Genes

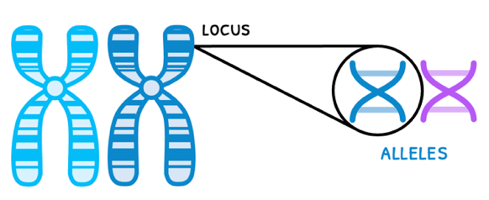

Topic D3.2 focuses on inheritance of genes by offspring. Genes are defined as a heritable factor consisting of a length of DNA that influences a specific characteristic. Such an example of a characteristic is hair.

Different versions of this gene are called alleles, which each code for a different version of that characteristics. An example would be that three alleles would code for blonde, brown, or black hair, respectively. However, only one allele can occupy a position on a chromosome, called a locus.

Loci have a specific notation:

- This starts with the number of the chromosome.

- Then, p stands for short arm and q stands for the long arm.

- Lastly, the position of the gene is listed.

For example, the human gene for the hemoglobin β-polypeptide is gene 15.4 on the short arm of chromosome 11. Its notation is thus 11p15.4.

Alleles

Alleles only differ from one another by a few bases due to mutations. You will learn more about these later in this topic. However, it is important to remember that every human only has two alleles, one from their father and one from their mother. You may notice that only one of these alleles actually is expressed.

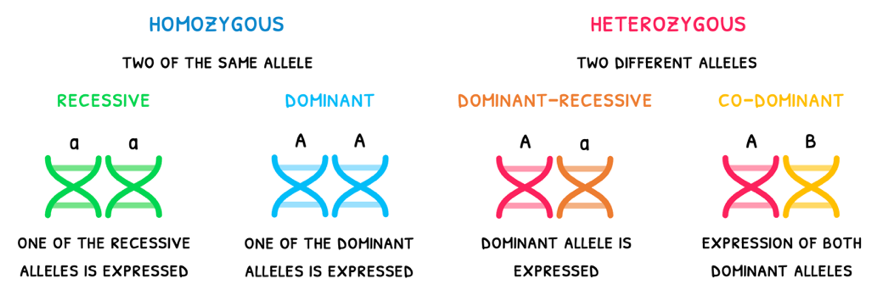

The phenotype is expressed physical characteristic of an organism. The genotype is all the alleles within an organism that code for this phenotype. The expressed phenotype is thus dependent on the type of allele, of which there are two types:

- Dominant allele - this allele is always expressed.

- Recessive allele - this allele is only expressed in the absence of a dominant allele.

Since there are two alleles, a few combinations are possible. These are split into two major categories:

- Homozygous - two of the same type of allele. This is split into two types:

- Dominant - two dominant alleles, resulting in a dominant phenotype.

- Recessive - two recessive alleles, resulting in a recessive phenotype.

- Heterozygous - two different types of allele. This is also split into two types:

- Dominant-recessive - one dominant and one recessive allele, resulting in a dominant phenotype.

- Co-dominant - two different dominant alleles, resulting in both phenotypes being expressed.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D3.2: Polygenic inheritance (HL)

Segregation

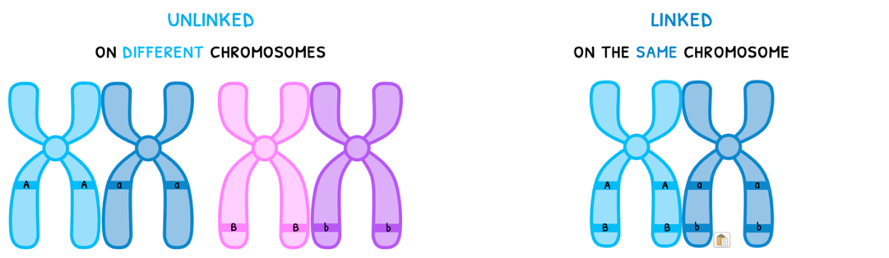

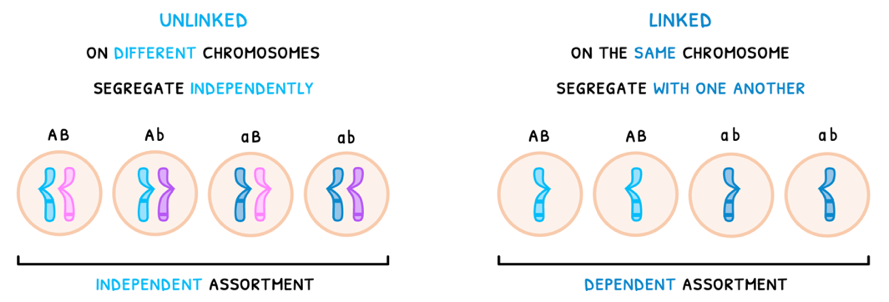

In the HL syllabus, you are expected to understand the inheritance of two genes, called digenic inheritance. In digenic inheritance, the types of genes involved in inheritance affect the end result. There are two main types:

- Unlinked genes are found on different chrosomes. As a result, they separate independently of one another, called independent assortment. As a result, four unique gametes are formed.

- Linked genes are found on the same chromosome. As a result, they separate together, called dependent assortment. As a result, two unique gametes are formed.

Note that if linked genes are far apart, they may be exchange during crossing over. This results in four unique gametes, making them appear unlinked.

Unlinked genes

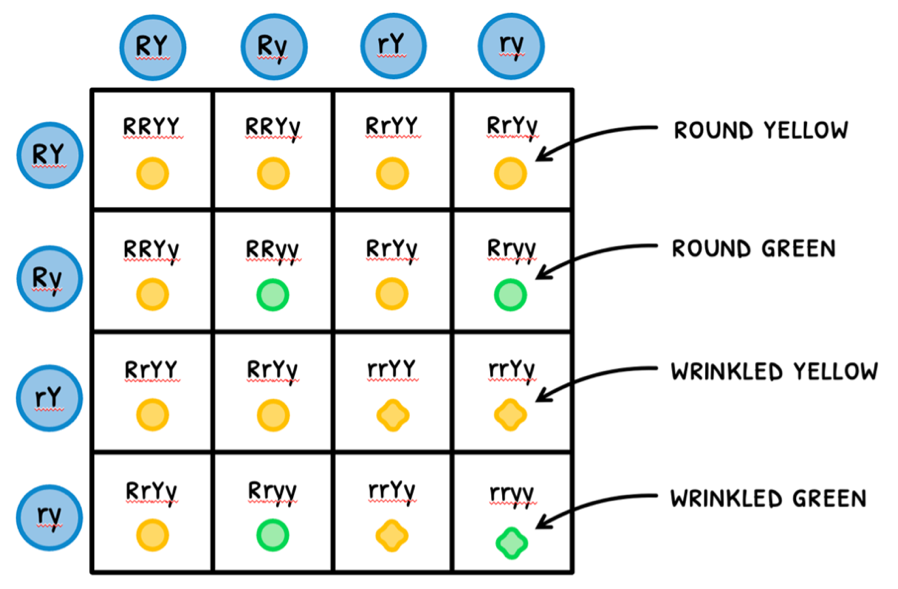

You are expected to understand how gene linkage and crossing over impact the resulting digenic inheritance. Let's begin with unlinked genes for heterozygous peas. Here, the allele for a round shape (R) is dominant to wrinkled (r), and a yellow color (Y) is dominant to a green color (y):

- Draw the four possible gametes of Parent 1 and Parent 2 in circles around the table.

- Then cross-reference them like in Punnett grids to determine the genotype of the offspring.

- Then determine the phenotype of each genotype.

In a heterozygous cross, this results in a phenotype ratio of 9:3:3:1. However, you are also expected to understand the ratio that forms during a homozygous cross. Using the same alleles:

- Draw the four possible gametes of Parent 1 and Parent 2 in circles around the table.

- Then cross-reference them like in Punnett grids to determine the genotype of the offspring.

- Then determine the phenotype of each genotype.

Thus, in a homozygous cross, a phenotypic ratio of 1:1:1:1 is present.

Sail through the IB!

D3.3: Homeostasis

Homeostasis

The last component of Topic 3, this subtopic focuses on how the body communicates between organs via hormones, maintains itself via homeostasis, and the key components involved in reproduction.

Homeostasis should be familiar as a core function of life. It is defined as the ability to maintain a constant internal environment, and this can take many forms.

In this topic, you need to learn about the homeostasis of:

- Glucose concentration - via insulin and glucagon.

- Thermoregulation - via thyroxine.

Blood glucose regulation

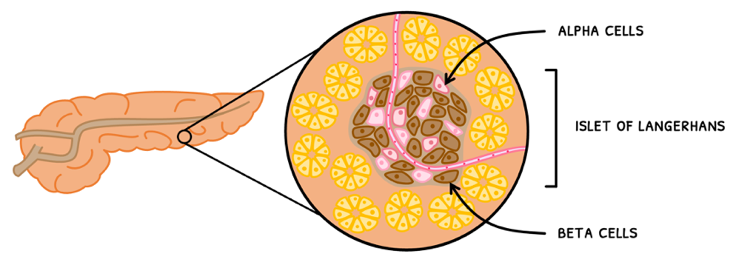

Let's start with glucose concentration, controlled by the pancreas. Remember that it secretes digestive enzymes during digestion. This is part of its exocrine function (secretion into ducts), performed by duct cells. However, it also has an endocrine function (secretion into blood), performed by Islets of Langerhans. These primarily contain:

- Alpha cells - these secrete glucagon into blood.

- Beta cells - these secrete insulin into blood.

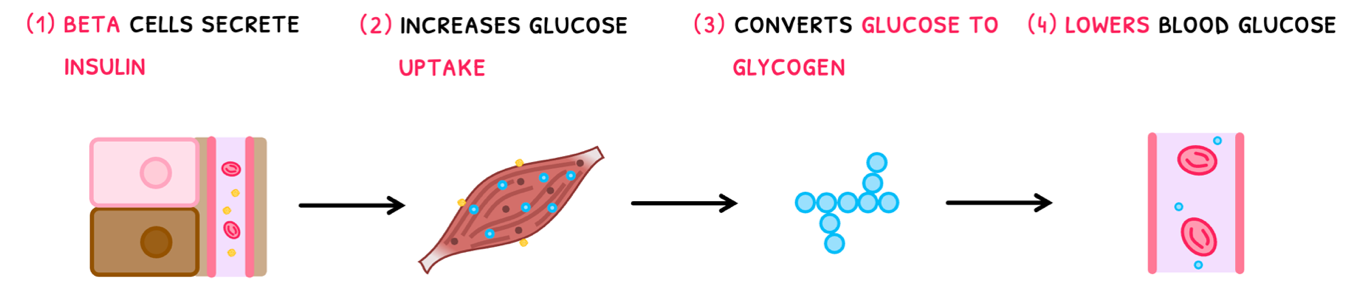

The pancreas thus releases one of these hormones when blood glucose concentration is imbalanced. When blood glucose concentration is high:

- Beta cells secrete insulin.

- This binds to insulin receptors in skeletal muscle and liver cells, stimulating an increase in glucose uptake.

- These sites convert the glucose to glycogen for storage.

- As a result, blood glucose concentration decreases.

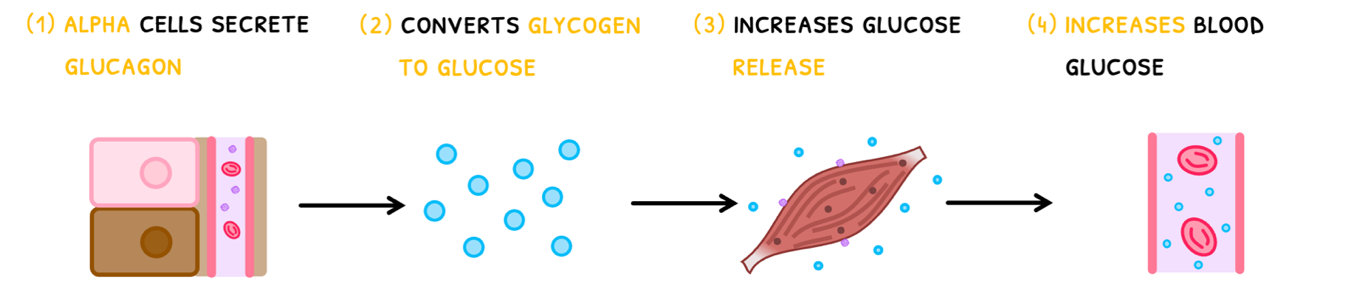

When blood glucose concentration is low:

- Alpha cells secrete glucagon.

- It converts glycogen to glucose, for metabolism.

- It then stimulates skeletal muscle and liver cells to release glucose into the blood.

- As a result, blood glucose concentration rises.

You can remember which hormone does what with the phrase: "When all the glucose has gone, we need glucagon."

Diabetes

However, this feedback mechanism can fail, causing serious consequences. Failure of glucose regulation can lead to a condition known as Diabetes Mellitus, characterized by a consistently elevated blood glucose. This often leads to downstream symptoms, such as damage to the eyes, kidneys and feet.

Sail through the IB!

D3.3: Further homeostasis (HL)

Osmoregulation

In the HL syllabus, you need to also know about homeostasis in the context of water and solute concentration, called osmoregulation. Organisms can be classified into two groups based on their level of osmoregulation: osmoregulator or osmoconformer.

- Osmoregulators are organisms that conduct osmoregulation because their solute concentration is different than that of their surroundings. This generally occurs in terrestrial animals and freshwater fish.

- Osmoconformers are organisms that do not conduct osmoregulation because their solute concentration is identical to that of their surroundings. This generally occurs in saltwater organisms.

Correct osmoregulation is very important for proper body function. However, this is sometimes not sufficient to prevent the extremes of water regulation: overhydration and dehydration.

- Overhydration is caused by excessive water consumption or retention without replacing electrolytes. It causes cell swelling and nerve dysfunction, which leads to:

- Headaches and confusion

- Blurred vision and nausea

- Dehydration is caused by excessive water loss or insufficient consumption without replacing electrolytes. It causes decreased muscle function and increased waste, which leads to:

- Dark concentrated urine

- Increased heart rate

- Inability to sweat (which can cause overheating and further dehydration)

Kidney structure

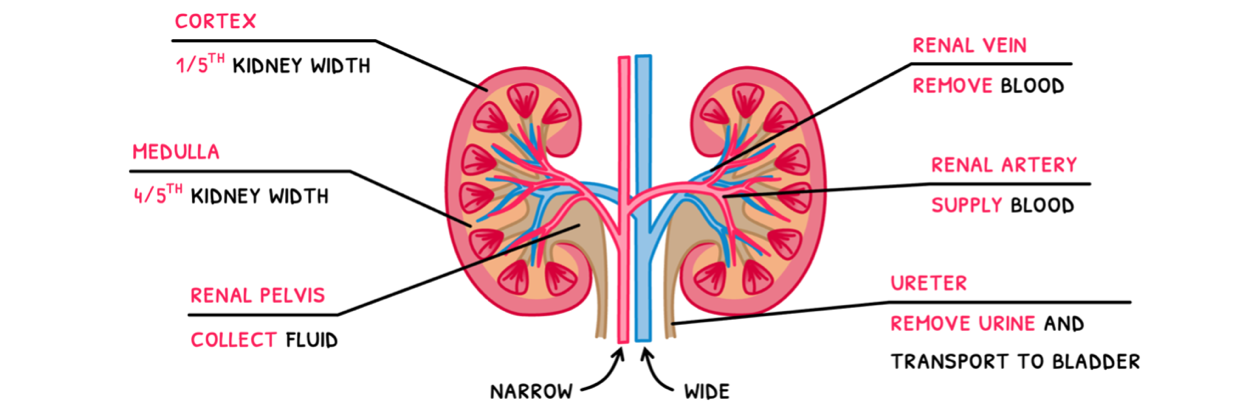

The process of osmoregulation in the kidneys is far more complicated. Let’s start by covering its structure. The kidneys are composed of:

- A renal artery – this supplies blood to the kidney. Remember that arteries have a narrow lumen.

- A renal vein – this removes blood from the kidney. Remember that veins have a wide lumen.

- An outer cortex – a region about 1/5th kidney where mainly solute reabsorption occurs.

- An inner medulla – a region about 4/5th of the kidney where the mainly water reabsorption occurs.

- A renal pelvis – central region of the kidney that collects the resulting urine.

- A ureter – a tube that removes urine from the pelvis and transports it to the bladder.