IB Biology Topic 1 Notes

A1.1: Water

Structure of water

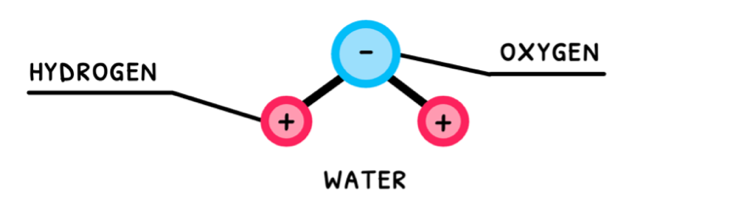

Water is the most essential molecule needed to sustain life on Earth. Also known as dihydrogen monoxide, it is composed of two hydrogen atoms covalently bonded to an oxygen atom. The sharing of electrons in these bonds is unequal, which means that water is a polar molecule!

Polar molecules with hydrogen and one of nitrogen, oxygen, or fluorine exhibit hydrogen bonding. Water fits this description, and thus exhibits hydrogen bonding between its molecules. Water’s polarity and its hydrogen bonding are the reason it is so versatile and the primary molecule we search for when attempting to detect alien life.

Properties of water

For the IB, you are expected to understand that water has four main properties: cohesion, adhesion, thermal properties, and solvent properties. Let’s go through each of those in detail.

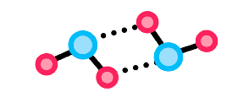

Cohesion is the ability of molecules within a substance to stick to one another due to intermolecular forces. In water, the molecules stay together via their hydrogen bonding, meaning they can form a continuous surface.

Examples of this are when cohesion forms one continuous water stream to travel in the xylem of plant stems or when it forms one continuous surface upon which insects can stand and walk.

Adhesion is the ability of molecules within a substance to stick to molecules of another substance due to intermolecular forces. Since water is polar and capable of hydrogen bonding, remember from Topic 2.1 that water will be able to form:

- Dipole-dipole forces with other charged, polar molecules, and hydrogen bonding with other H-NOF molecules. Molecules like this are considered hydrophilic since they would be attracted to water and able to bond with it.

- No strong intermolecular bonds with non-polar molecules, which would be considered hydrophobic since they would not be attracted to water and not bond with it.

An example of this is when adhesion sticks water to the polar cell walls of leaf cells to draw them out of xylem into the leaves.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

A1.1: Origin of water (HL)

Origin of the Solar System

Now that you have learned about the properties of water, you can appreciate how vital it is to life on Earth. In fact, 70% of our bodies and 70% of the Earth's surface are composed of water, highlighting its importance to life. However, the Earth did not always have this much water.

You are expected to understand how these water levels formed on Earth. To understand this, let's start from the beginning:

- Approximately 4.6 billion years ago, part of a molecular gas and dust cloud collapsed on itself.

- It begun to rotate faster during its collapse and form a hot protostar center and colder protoplanetary disc.

- Gravity condensed the center into the Sun and dust and gas in the disc into hundreds of protoplanets.

- Many of these were ejected, destroyed or collided and merged to form the early planets of the Solar System.

- Solar winds and the high temperatures of the inner Solar System removed hydrogen and helium, forming the rocky planets of Mercury to Mars.

- Further planets were far enough away that solar winds and low temperatures allowed gases to remain and expand, forming the gas giants of Jupiter to Uranus.

- Leftover debris congregated in asteroid belts.

Extraplanetary origin of water

Knowing the initial formation of the Solar System, we can move to the development of the Earth:

- Early Earth was mostly molten due to intense volcanic activity.

- Eventually, the Earth to cool enough to form a solid crust and core, leading to the formation of the Earth's magnetic field.

- The magnetic field stabilized Earth's atmosphere and preventing it from being stripped away by solar winds.

- At some point, a Mars-sized object collided with the Earth, releasing material from the mantle which became trapped in orbit, forming the Moon.

- Further plate tectonic activity caused mantle flow, leading to mountain formation and volcanic activity, releasing gases.

- Cooling of the planet and gravity caused the gases to be retained, creating a denser atmosphere.

- The arrival of water is explained by the Asteroid Theory. This states that water abundant asteroids from the asteroid belt entered the inner Solar System and collided with Earth, depositing much water on Earth's surface.

- Coupled with Earth's gravitational pull, this helped water retention to form oceans and seas. Due to the atmosphere and ideal distance from the Sun, vaporization did not occur, maintaining its liquid form.

Evidence of these theories is largely derived from studies exploring the Hydrogen isotope Deuterium. Its presence in equal ratios in water and asteroids and unequal ratios in many parts of the Earth's crust support the Asteroid Theory.

Sail through the IB!

A1.2: Nucleic acids

Nucleotides

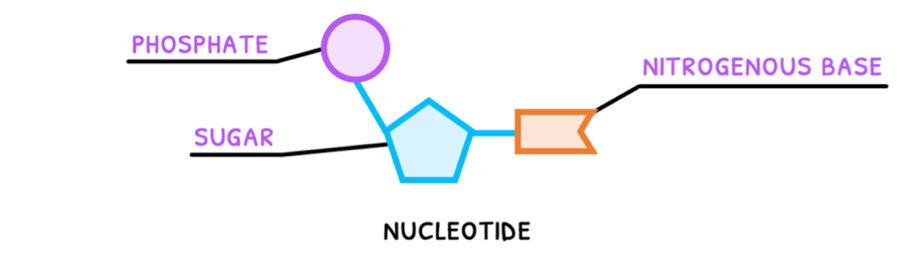

Organic molecules are typically divided into four types. The first of these you need to know about is nucleic acids, whose function is to code for proteins. Nucleic acids all have base units (monomers), called nucleotides. These have three main components:

- Phosphate group - a PO43- group connected to the 5' carbon of the pentose sugar.

- Sugar ring - deoxy-D-ribose or D-ribose pentose ring connected to a nitrogenous base at the 1' carbon and a phosphate group at the 5' carbon.

- Nitrogenous base - one of adenine, thymine, cytosine, guanine, or uracil, connected to the 1' carbon of the pentose sugar.

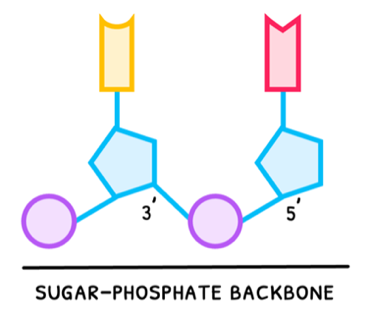

Nucleotides are subsequently connected together via condensation reactions, forming a connection between the 3' carbon of one nucleotide and the phosphate group of another nucleotide. Altogether this forms an alternating pattern of phosphates and sugars, called the sugar-phosphate backbone.

Nucleic acids

Connecting many nucleotides together via this sugar-phosphate backbone begins to form nucleic acids. There are two forms you need to be aware of: DNA and RNA.

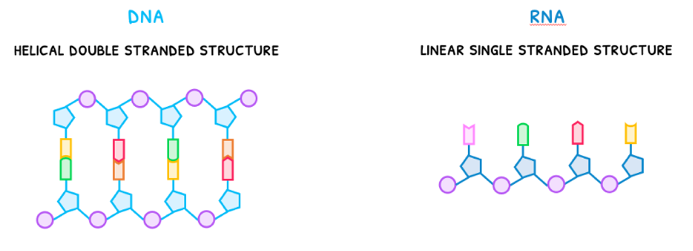

- DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid, is a helical double stranded structure.

- RNA, ribonucleic acid, is a linear single stranded structure.

Sail through the IB!

A1.2: Further nucleic acids (HL)

Hershey and Chase

In the HL syllabus, you need to understand more about nucleic acids. Whilst Watson and Crick discovered the structure of DNA, two other important scientists conducted their own research to determine what genetic material was composed of. These were Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase - who proved that genes are composed of DNA, not protein.

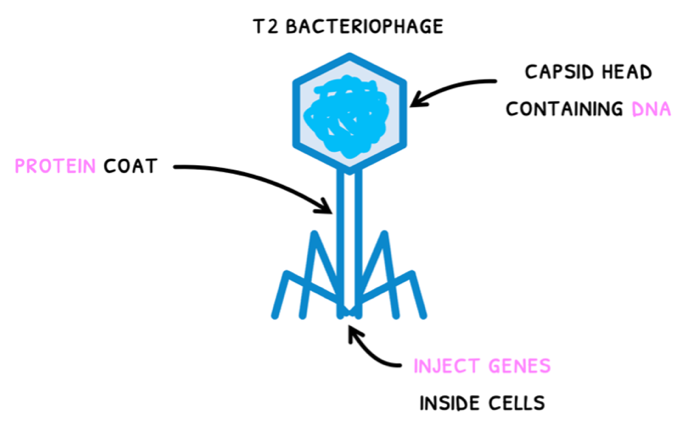

The foundation of their work revolved around the investigation of T2 bacteriophages. These are viruses that infect bacteria and were determined to be composed of:

- An outer protein coat with a capsid head and a tube leading to an injection site. Remember that protein contains sulfur, but not phosphate.

- DNA contained inside the capsid head. Remember that DNA contains phosphate, but not sulfur.

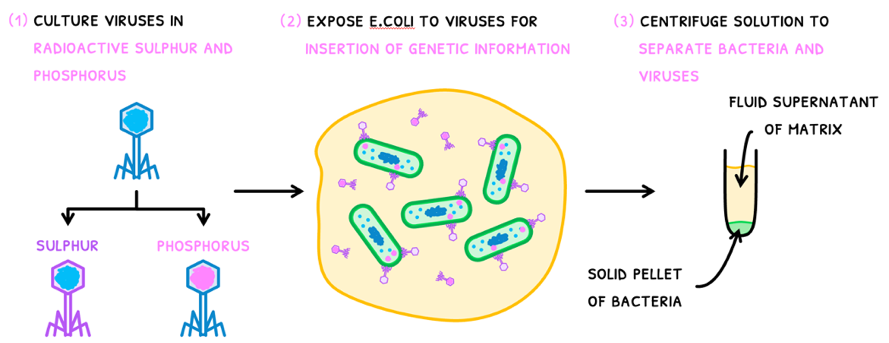

It was known that these viruses would use bacteria as their hosts to replicate themselves, like what HIV does in T cells. Questions, however, remained about which element of the bacteriophage was its genetic material. The experiment Hershey and Chase conducted involved:

- Culture a group of viruses in radioactive sulfur - giving them a radioactive protein coat. Culture another group of viruses in radioactive phosphate, giving them radioactive DNA.

- Expose E.coli to the viruses for the insertion of genetic information.

- Centrifuge the solution to separate the bacteria and the viruses. This creates two layers:

- A solid pellet of the compacted cells containing the genetic material.

- A fluid supernatant of extracellular matrix that does not contain the genetic material.

Hershey and Chase had the following results:

- The majority of the sulfur's radioactive signature was present in the supernatant, indicating protein was not inserted in the cell.

- The majority of the phosphate's radioactive signature was present in the pellet, indicating DNA was inserted in the cell.

However, some sulfur was present in the pellet and some phosphate in the supernatant. Further research found why this was the case:

- After injection of DNA, some protein coats remained attached to the cells and were thus taken into the pellet.

- Some viruses did not inject their DNA at all, so this content remained in the supernatant.

Explanation of this discrepancy finally concluded that DNA was indeed the genetic material inserted into cells for replication of viruses.

Sail through the IB!

B1.1: Carbohydrates and lipids

Atoms and bonding

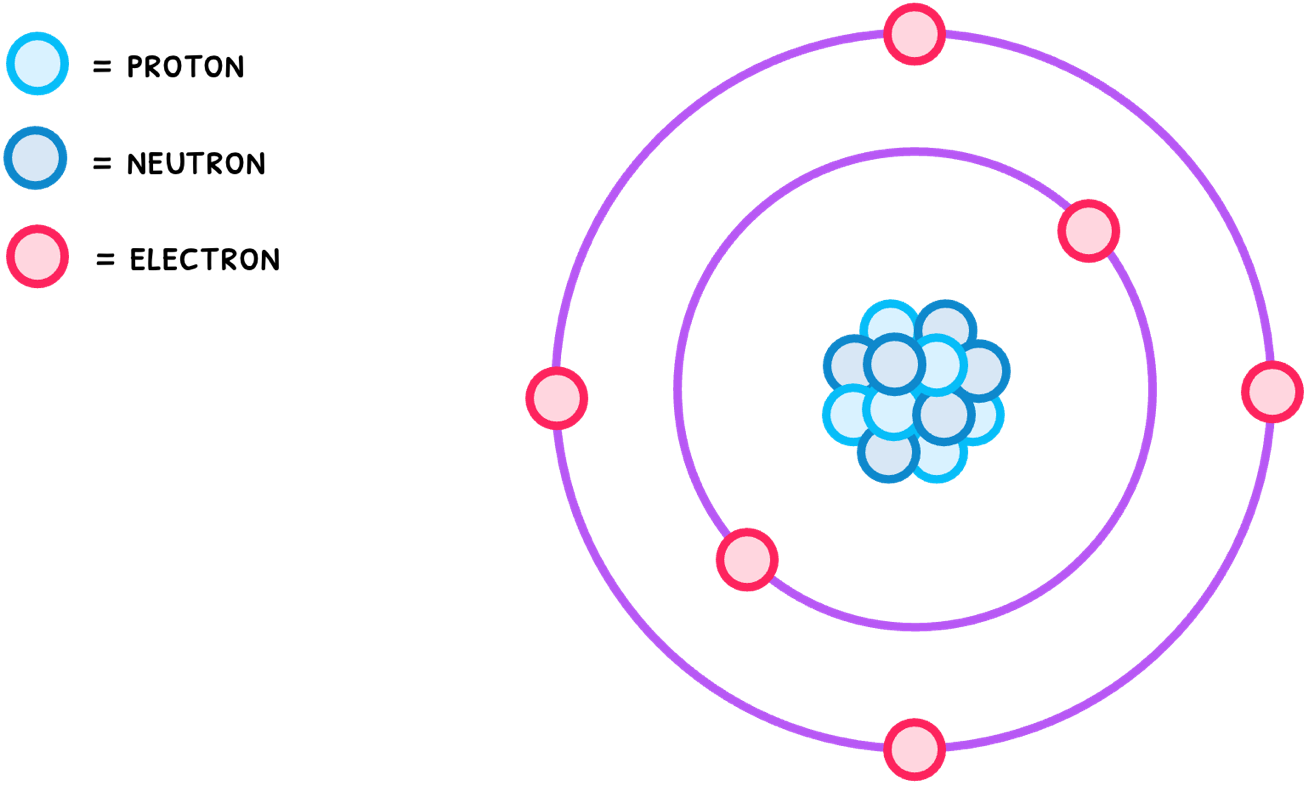

This topic predominantly focuses on the living processes of cells and organisms in terms of the chemical reactions involved, called molecular biology. For this, it is important to understand what molecules are and how they are held together. To provide a complete understanding, let’s start with atoms.

Atoms are the most basic unit of an element, composed of protons and neutrons in a nucleus, surrounded by orbiting electrons, as shown below.

When two atoms come close together, the nucleus of one atom attracts the electrons of the other and vice versa. This ends up meaning that the two nuclei will share electrons between themselves, forming what is called a covalent bond. There are three types of covalent bonds:

- Single covalent bond – each atom shares one electron, placing two electrons in the bond.

- Double covalent bond – each atom shares two electrons, placing four electrons in the bond.

- Triple covalent bond – each atom shares three electrons, placing six electrons in the bond.

Polar and non-polar bonds

Molecules are thus the complexes that form when two or more atoms are held together by covalent bonds. Ultimately, how the electrons are shared determines what type of molecule is formed. Electrons can be shared in two ways: equally or unequally.

- The electrons can be shared equally, meaning both nuclei have the same strength and so the electrons lie in the middle of the bond.

- The electrons can be shared unequally, meaning one nucleus is stronger and so pulls the electrons in the bond closer to itself.

As a result of this electron sharing, two types of molecules are formed: polar or non-polar.

- Polar molecules are formed when there is unequal sharing, so one side of the molecule has more electrons than the other. As a result, the molecule has a negatively charged pole and a positively charged pole, called a dipole.

- Non-polar molecules are formed when there is equal sharing, so all sides of the molecule have the same number of electrons and no poles form.

Macromolecules and monomers

Now that you understand how molecules are formed and whether they are polar or non-polar, you need to understand that organic molecules are categorized into two types:

- Monomers - these are the simplest units of organic molecule types. Examples include:

- Monosaccharides - carbohydrate monomers.

- Amino acids - protein monomers.

- Nucleotides - DNA and RNA monomers.

- Macromolecules - these are monomers linked together to form larger molecular structures. Two monomers linked together are called a dimer, and three or more monomers linked together are called a polymer. Examples include:

- Polysaccharides - carbohydrate macromolecules

- Polypeptides - protein macromolecules

- Nucleic acids - nucleic acid macromolecules

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B1.2: Proteins

Proteins

The next molecular group to cover is proteins. Proteins are a group of molecules composed of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and sometime sulfur. For the SL curriculum, you are expected to only understand it has three levels of structure: amino acids, dipeptides, and polypeptides.

Amino acids

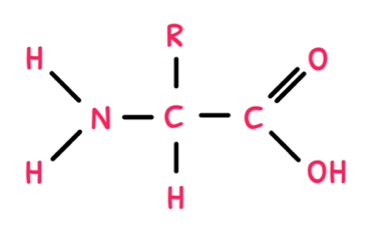

It is easier to think of these levels in comparison to carbohydrates. Just as monosaccharides are the monomers of carbohydrates, amino acids are the monomers of proteins. There are twenty different amino acids, each containing a central carbon bonded to an NH2 (amine) group, a COOH (carboxyl) group, a hydrogen, and an R-group. The R-group is variable, meaning it could be anything from just a hydrogen to a complex side group, and its structure determines the type of amino acid formed.

Collectively, amino acids are used to produce protein, hormones, and enzymes whilst being important in the regulation of digestion and gene expression. Plants are able to synthesise all 20 amino acids, whereas only 11 can be produced naturally by animal cells; these are called ‘non-essential’ as they are not required in the diet. However, the remaining 9 amino acids must be taken in dietarily and as such are referred to as ‘essential’.

| Essential | Non-essential |

|---|---|

| Histidine | Alanine |

| Isoleucine | Arginine |

| Leucine | Asparagine |

| Lysine | Aspartic Acid |

| Methionine | Cysteine |

| Phenylalanine | Glutamic Acid |

| Threonine | Glutamine |

| Tryptophan | Glycine |

| Valine | Proline |

| Serine | |

| Tyrosine |

As vegans do not consume animal foods which are rich in essential amino acids, they must rely on plant-based foods to acquire their essential amino acids. Plant foods often contain some, but not all the essential amino acids and so are incomplete proteins. For example, nuts, beans and grains.

This can be ameliorated by careful combining of plant foods to consider all 9 essential amino acids. For example, the combination of rice and beans provides all 9 essential amino acids.

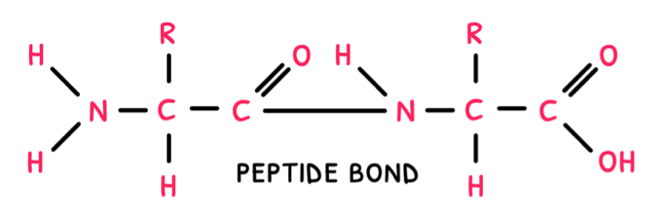

Peptide bonds

Next, just as disaccharides are composed of two monosaccharides, dipeptides are composed of two amino acids. Same as disaccharides, dipeptides are formed via a condensation reaction and broken down via a hydrolysis reaction. Instead of a glycosidic link, these reactions form or break a peptide bond.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

B1.2: Further proteins (HL)

R-groups

Whilst you now understand the basic structure of proteins and how they form polypeptides via peptide bonds, you know need to understand how these form 3D structures to become mature proteins. This all begins with R-groups, which is the only chemically variable component of the amino acid.

It is this variable group that provides the different amino acids with a host of different properties:

- Hydrophobic R-groups - in soluble proteins, folded into the protein’s interior. In insoluble proteins, present on the protein's exterior.

- Hydrophilic R-groups - in soluble proteins are arranged on the exterior of the protein

- Polar R-groups - participate in dipole-dipole bonding and hydrogen bonding.

- Charged R groups - create electrostatic attractions or repulsions which will influence the ultimate structure, stability and function of the protein.

Some R-groups are pH sensitive and accept or donate protons in accordance with the surrounding pH. This variation in R-groups and its accompanying effect on all potentially different chemical properties facilitates proteins versatility in a host of different functions, to include catalytic, transport, building and signal transduction.

Protein structure

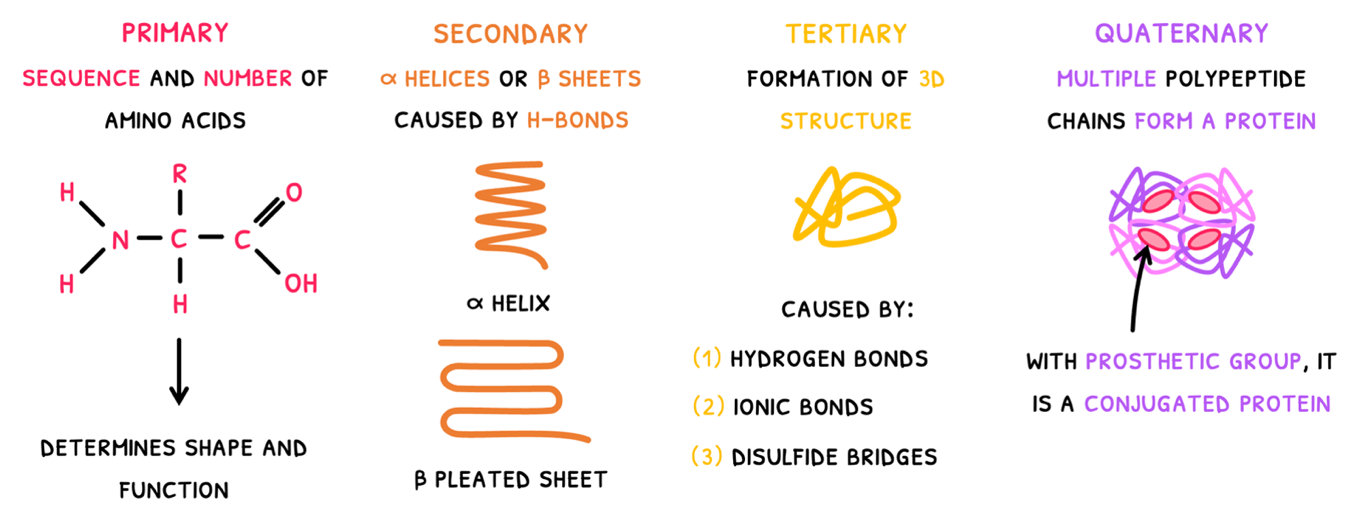

Once a polypeptide chain has been formed, it can fold to form the protein. You are expected to be familiar with the four levels of protein structure:

- Primary structure - this is simply the sequence and number of amino acids in the polypeptide chain. It ultimately determines the 3D shape and function of the protein. As a result, proteins have predictable and repeatable structures to attain a specific shape.

- Secondary structure - this is the first level of folding where carboxyl and amine groups of amino acids form hydrogen bonds forming one of two structures:

- The α helix - which is spiral in shape.

- The β pleated sheet - which is made of parallel straight chains.

Tertiary structure - this is the second level of folding, where the polypeptide forms a 3D structure. It results from a number of bonds:

- Hydrogen bonds between H-NOF R-groups.

- Ionic bonds between charged R-groups. Amine and carboxyl groups can also participate in this by binding or releasing H+ ions to become charged.

- Disulfide bridges between cysteines.

- Dipole-dipole forces between polar R-groups. In soluble proteins, these are found on the outside of the protein, whilst in integral proteins, they are found on either end of the protein.

- London dispersion forces between non-polar R-groups. Since these are hydrophobic, they are clustered in the core of soluble proteins, but take up the middle region of an integral protein.

The tertiary structure is the final structure of some proteins, but many have an additional level of structure.

Quaternary structure - this is the combination of two or more polypeptide chains to form a final protein. Common examples include:

- Insulin - composed of two polypeptide chains bound together as a globular protein.

- Collagen - composed of three polypeptide chains twisted together as a fibrous protein.

- Haemoglobin - composed of four polypeptide chains huddled together as a globular protein.

Insulin and collagen are non-conjugated proteins, but haemoglobin is an example of a conjugated protein. Conjugated proteins possess a non-protein group, called a prosthetic group. In hemoglobin, each polypeptide chains contains each a haem group with Iron to bind with oxygen.

C1.1: Enzymes & metabolism

Metabolism

In Topic C1.1, you focus on metabolism. An organism’s metabolism is defined as the complex network of interdependent and interacting chemical reactions occurring in living organisms. These chemical reactions can be divided into two types:

- Anabolic reactions – these are reactions that combine monomers to form macromolecules. As a rule of thumb, any anabolic reaction you see in IB Biology will be a condensation reaction. Remember that this produces a macromolecule and water.

- Catabolic reactions – these are reactions that break down macromolecules into monomers. As a rule of thumb, any catabolic reaction you see in IB Biology will be a hydrolysis reaction. Remember that this uses water to split a macromolecule.

Enzymes

Both anabolic and catabolic reactions are catalyzed by enzymes. They are defined as proteins that speed up the rate of chemical reactions by lowering their activation energy. Let’s explore this:

- Every chemical reaction requires an energy input to occur, called the activation energy. This can be thought of as a spark required to light a fire.

- This spark is usually provided when particles collide into one another during their random continual motion.

- When the resulting collision energy is higher than the activation energy of the reaction, then the “spark catches” and the reaction occurs. However, if the collision energy is lower than the activation energy, then the reaction does not occur.

Enzyme collisions

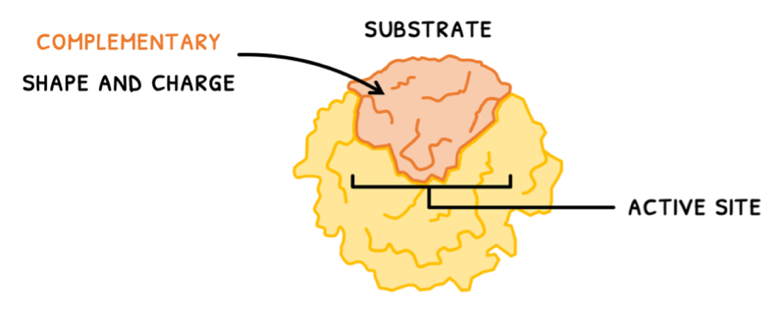

Enzymes are thus important to control metabolism and the rate at which it occurs. They do this by colliding with substrates at a binding region called the active site. This is composed of a few amino acids forming a 3D structure and requires substrates that have:

- A complementary shape and charge

- The correct orientation

- Sufficient collision energy

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C1.1: Further metabolism (HL)

Metabolic pathways

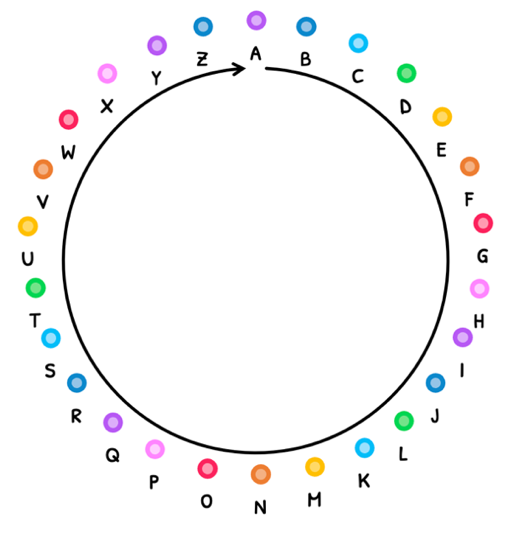

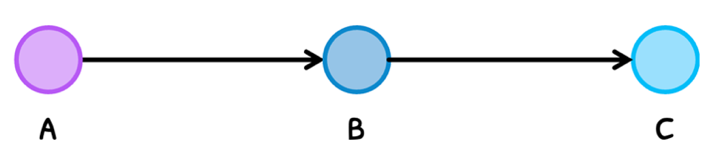

In the SL syllabus, you learned about metabolism and how enzymes catalyze metabolic reactions. In the HL syllabus, you are expected to know more detail about both of these aspects. To begin, you must be aware that metabolic networks are constructed of a series of pathways. These pathways are typically arranged as:

- Cycles - where a start molecule is changed over a series of reactions and reformed, allowing for a continuous pathway. Examples of cycles include the Krebs cycle and the Calvin cycle.

- Chains - where a start molecule is changed over a series of reactions to form an end molecule.

In either case, the pathway is always connected with control mechanisms that regulate the molecules. As a result, molecules are only produced when they are needed and destroyed when they are not needed.

Pathway location

Whilst the type of metabolic pathway is important its function, its location is too. In this sense, metabolic pathways can be divided into two types:

Extracellular - these are pathways undergone outside of the cells that typically act to break down macromolecules into monomers so that cells can interact with them. The immune destruction of pathogens is also considered to a function of extracellular metabolism.

Thus, important examples of extracellular pathways include the chemical digestion of food in the alimentary canal and phagocytosis/antibody-mediated destruction of pathogens.

Intracellular - these are pathways undergone inside of cells that typically act to use extract, convert and use energy from monomers.

Thus, important examples of intracellular pathways include glycolysis and the Krebs cycle in animals, with the Calvin cycle an additional cycle in plants.

Heat generation

The next component you are supposed to understand is that of heat generation in metabolic reactions. Many reactions are exothermic and release heat, particularly respiration. This is because bond formation in molecules releases energy as heat, which cannot be recovered. Thus, energy conversions in the body always operate at less than 100% efficiency.

However, this is not a bad thing. Since there is no other source of heat production, the heat generated by metabolism is essential in warm-blooded animals for several reasons:

- Cells and enzymes work optimally at 37°C, requiring the body to be maintained at this temperature.

- Heat production and energy loss create a necessary energy balance with food ingestion for nutrients and other essential compounds. Otherwise, this energy would only be absorbed with nowhere else to go.

- In cold conditions, metabolism can be upregulated to sustain body warmth and prevent freezing.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C1.2: Respiration

ATP and ADP

When considering cells and metabolism throughout IB biology, you need to understand that the energy required for all processes needs to come from somewhere. It always appears in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

ATP is a nucleotide and is the universal energy currency of the cell. In animals it is synthesised in the mitochondria via oxidative phosphorylation. It is often likened to a rechargeable battery as when a cell requires energy, ATP splits off one of its 3 phosphates via hydrolysis to become ADP (adenosine diphosphate) releasing energy in the process. ADP is then ‘recharged’ with an inorganic phosphate ion back to ATP as and when required. This is what is meant by the ATP-ADP cycle.

The hydrolysis of ATP into ADP releases free energy as it is an exergonic process; in animals up to 60% of this is lost as heat – rather than all of it fuelling the actual chemical reactions taking place.

Cell respiration

However, for ATP to be used in cellular processes, it needs to be generated from ADP and phosphate. This is done by cell respiration, defined as how a cell produces its own ATP from organic compounds. As a result, ATP is immediately usable as an energy source anywhere in the cell for any process.

During this, the organic compounds used are primarily carbohydrates (particularly glucose), followed in order of preference by lipids and proteins.

Do note that cell respiration is different than gas exchange. Gas exchange refers to the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide during ventilation in the respiratory system of animals, whilst respiration refers to the continuous generation of ATP.

Types of cell respiration

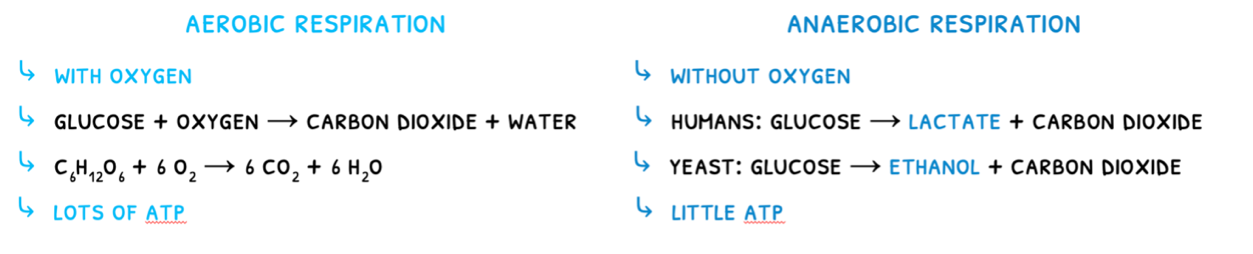

There are two types of cell respiration:

- Aerobic respiration - respiration that uses oxygen. This occurs in the cytoplasm and mitochondria.

- Anaerobic respiration - respiration that does not use oxygen. This only occurs in the cytoplasm and does not require mitochondria.

The type of respiration used in dependent on the situation. Although anaerobic respiration does not provide a lot of ATP, it is very rapid and maximizes the power of muscle contractions. It is thus used in muscles carrying out vigorous exercise such as sprinting or lifting.

HL students need to learn the process of respiration in more detail.

Sail through the IB!

C1.2: Further respiration (HL)

Cell respiration

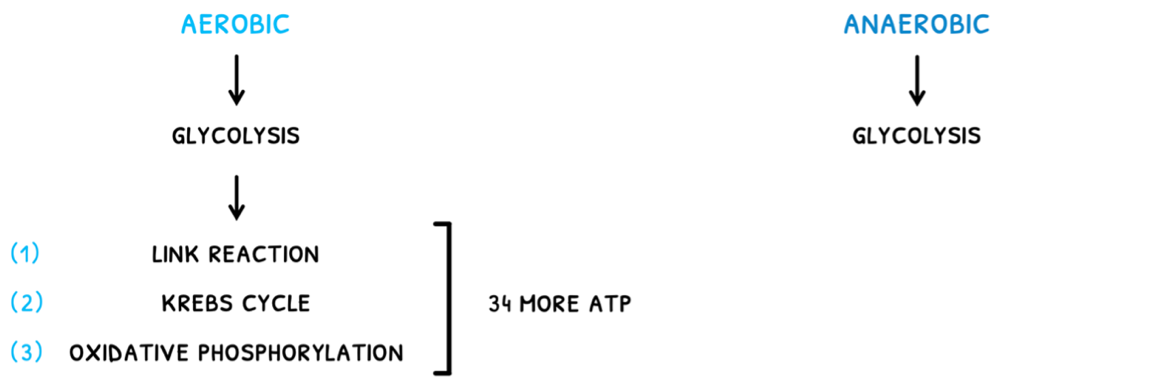

Remember that cell respiration is the process by which a cell releases energy, in the form of ATP, from its organic compounds. You learned that it is divided into two types: aerobic and anaerobic. In this topic, you will learn about the specific reactions that occur in each type. To summarize:

- In anaerobic respiration, only glycolysis occurs.

- In aerobic respiration, glycolysis is followed by the link reaction, Krebs cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation. This ends up producing around 34 more ATP molecules.

Oxidation and reduction

Additionally, to understand what occurs in the reactions it is important to understand two terms: oxidation and reduction.

- Oxidation is the loss of electrons.

- Reduction is the gain of electrons.

However, it is sometimes difficult to see how electrons are transferred, so two alternate definitions can be used:

- Oxidation is the gain of oxygen or the loss of hydrogen.

- Reduction is the loss of oxygen or the gain of hydrogen.

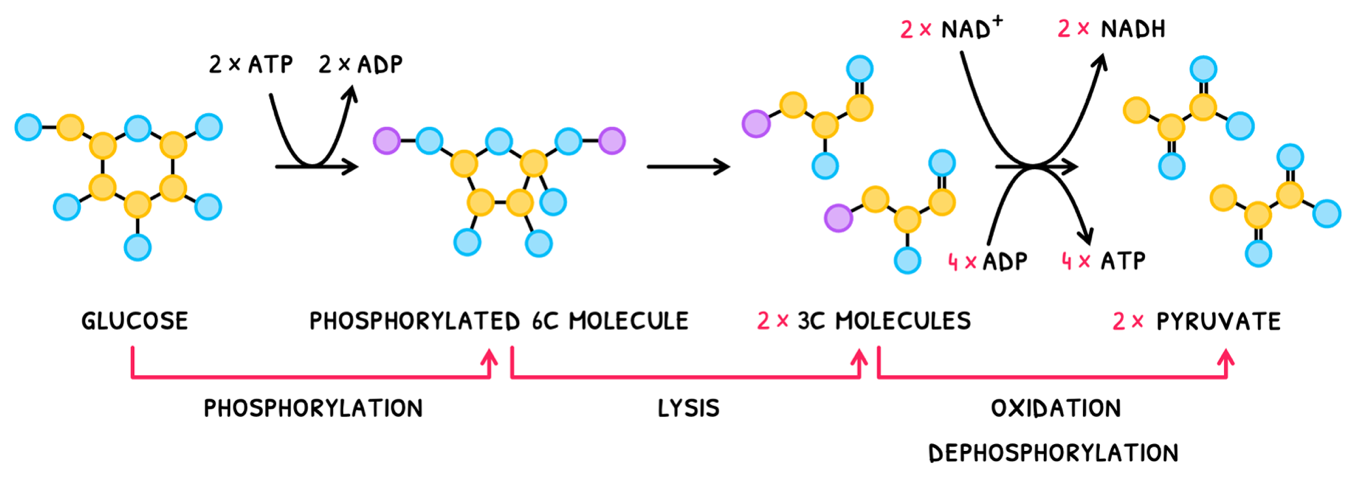

Glycolysis

Now that you know the basics, let's discuss the stages of respiration, starting with glycolysis. In this:

- Glucose is phosphorylated using 2x ATP to form an unstable phosphorylated 6 carbon molecule.

- This unstable phosphorylated 6 carbon molecule then splits by lysis to form 2x 3 carbon phosphorylated molecules.

- Each of these then undergoes oxidation, losing a H to NAD+, which is reduced to form NADH.

- Each also undergoes dephosphorylation, producing 4x ATP total.

The resulting molecule formed is named pyruvate. Therefore, a net 2 NADH, 2 ATP and 2 pyruvates are formed in total. Note the uset of "net" here as 2 ATP were used in the first reaction.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C1.3: Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis

Whilst respiration uses oxygen and organic compounds to produce energy, photosynthesis does nearly the opposite. It is the production of organic compounds and oxygen from light, CO2, and water. This reaction is only conducted in certain types of organisms - namely plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. The specific reaction they undergo is:

CO2 + H2O → glucose + O2

A summary of the process is:

- First, light energy is absorbed by photosynthetic pigments called chlorophyll.

- This energy is used to split water molecules in a process called photolysis, producing electrons and oxygen as waste.

- Finally, the electrons are used to convert CO2 into organic compounds (glucose).

HL students need to learn a more detailed process.

Factors of photosynthesis

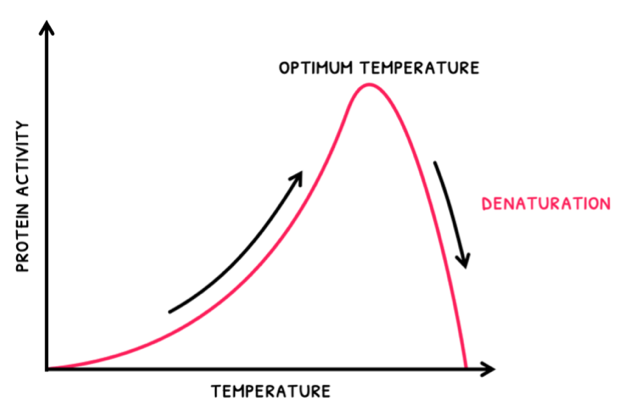

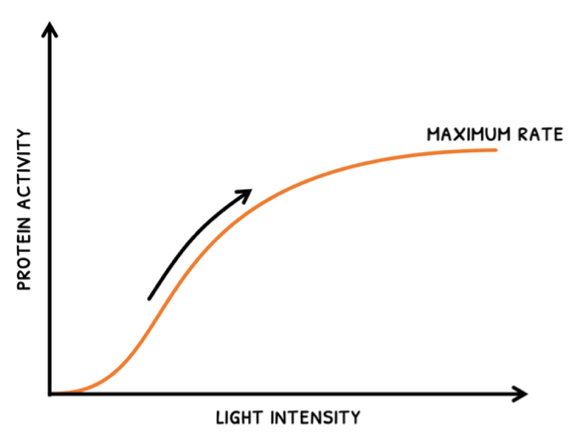

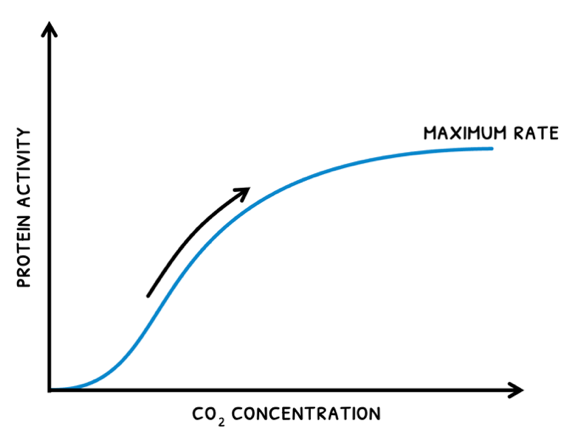

Next, it is important to consider the impact of several factors on photosynthesis. The main factors include temperature, light intensity, and carbon dioxide concentration.

- As temperature increases, rate increases to a maximum at an optimum temperature. After this, as temperature increases, rate decreases as enzymes become denatured.

- As light intensity increases, rate increases up to a maximum rate. After this, an increase in intensity does not affect rate because another factor will become limiting.

- As CO2 concentration increases, rate increases up to a maximum rate. After this, an increase does not affect rate because another factor will become limiting.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

C1.3: Further photosynthesis (HL)

Photosynthesis

You learned the basics of photosynthesis, which is the process by which a cell uses light, CO2, and water to generate organic compounds and O2. You learned that this process relies on chlorophyll to split water and use the electrons to produce organic materials. However, you need to learn this process in more detail.

Photosynthesis is typically divided into two stages:

- Light-dependent reactions - in this stage, light is used to split water and drive the phosphorylation of ADP into ATP and the reductiton of NADP into NADPH. This is also called photophosphorylation.

- Light-independent reactions - in this stage, ATP and NADPH are used to fix CO2 to form glucose and other organic compounds. The component of this you need to know is the Calvin cycle.

Light-dependent reactions

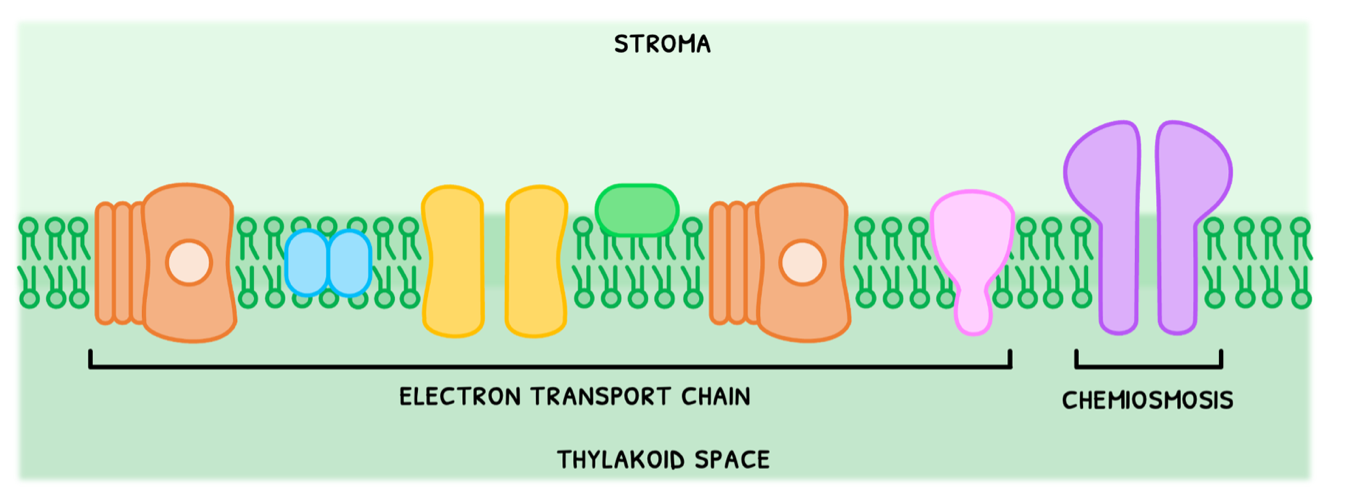

Now let's cover the light-dependent reactions. During this, light splits water into oxygen, electrons, and H+ via a process called photolysis. These are then used to phosphorylate ADP into ATP, hence the name photophosphorylation. Like aerobic respiration, this is split into two stages: the electron transport chain and chemiosmis.

However, photosynthesis involves an extra group of enzymes called photosystems. These photosystems are always present in a membrane in cyanobacteria and chloroplasts of photosynthetic eukaryotes to carry out photosynthesis. They are composed of:

- Molecular arrays of chlorophyll - note that using a single chlorophyll molecule would not absorb sufficient energy to perform any part of photosynthesis, but requires an entire array.

- Arrays of other accessory pigments

- A reaction center with a special chlorophyll that emits excited electrons.

- Electron transport chain - the process by which two photosystems reaction centers absorb light for photolysis, and subsequently donate the electrons to a series of proton pumps to facilitate the build-up of an H+ concentration gradient.

- Chemiosmosis - the process by which the energy from H+ flowing down its concentration gradient is used to phosphorylate ADP into ATP.

Electron transport chain

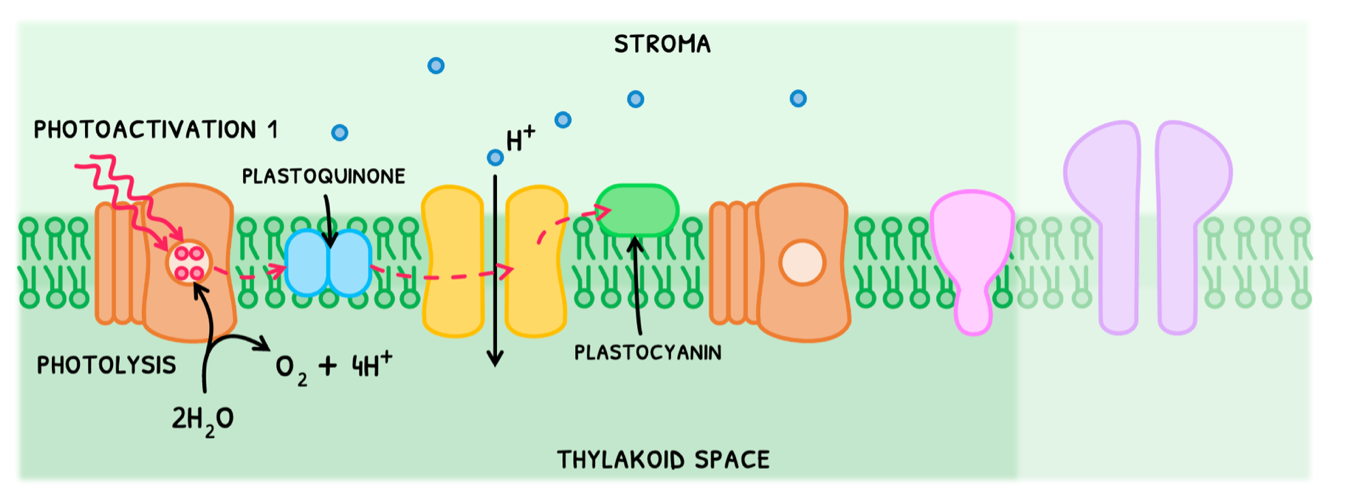

We can consider the electron transport chain in two halves. In the first half:

- Photosystem II undergoes photoactivation I, absorbing two photons of light to promote two electrons. This occurs twice to produce four electrons.

- These are donated to an electron acceptor called plastoquinone, reducing it.

- The photosystem now lacks four electrons, making it very reactive. It thus splits water into oxygen, four H+, and four electrons to replenish its electrons.

- Plastoquinone releases its four electrons to the next proton pump, each providing energy to pump one H+ into the thylakoid space.

- Once used, the electrons are accepted by another electron acceptor, known as plastocyanin, reducing it.

This pumps four H+ across and produces four H+ from photolysis, creating a high concentration gradient.

Sail through the IB!

D1.1: DNA replication

DNA replication

Once DNA's structure was determined, the process of its replication needed to be determined. At the onset, this was tied between three main theories of replication existing at the time:

- Conservative replication - the theory that both parent strands remain together (conserved), and an entirely new duplicate is formed.

- Semi-conservative replication - the theory that the parent strands break apart and each help form a new strand to produce two half-new and half-old copies.

- Dispersive replication - the theory that the parent strands are cut and split up randomly to then produce copies with random amount of old and new DNA.

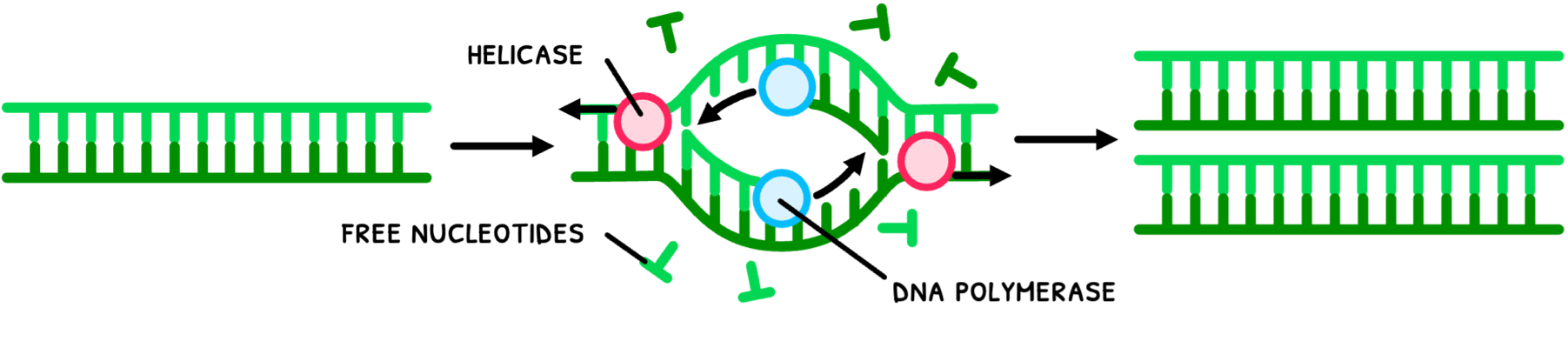

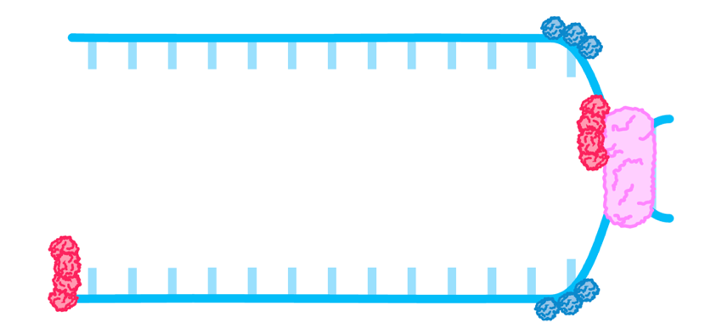

Meselson and Stahl determined that DNA replication was semi-conservative. You are expected to know this superficially, whilst HL students will learn this process in more detail. It occurs as follows:

- Helicase unwinds and separates the double helix by breaking hydrogen bonds between DNA strands.

- DNA polymerase links nucleotides to the pre-existing strands via complementary base pairing to form two new identical strands.

- The strands separate and wind back into a double helix.

This method of replication via complementary base pairing has a high accuracy as only certain nucleotides are able to bind to another successfully. Deep knowledge of the process also allows for a number of industrial applications, such as DNA profiling.

DNA profiling

DNA profiling is the analysis of sampled DNA for comparison to other individuals. Although this can be used to determine susceptibility to disease, the applications the IB wants you to be aware of is in crime scene investigations and paternity testing.

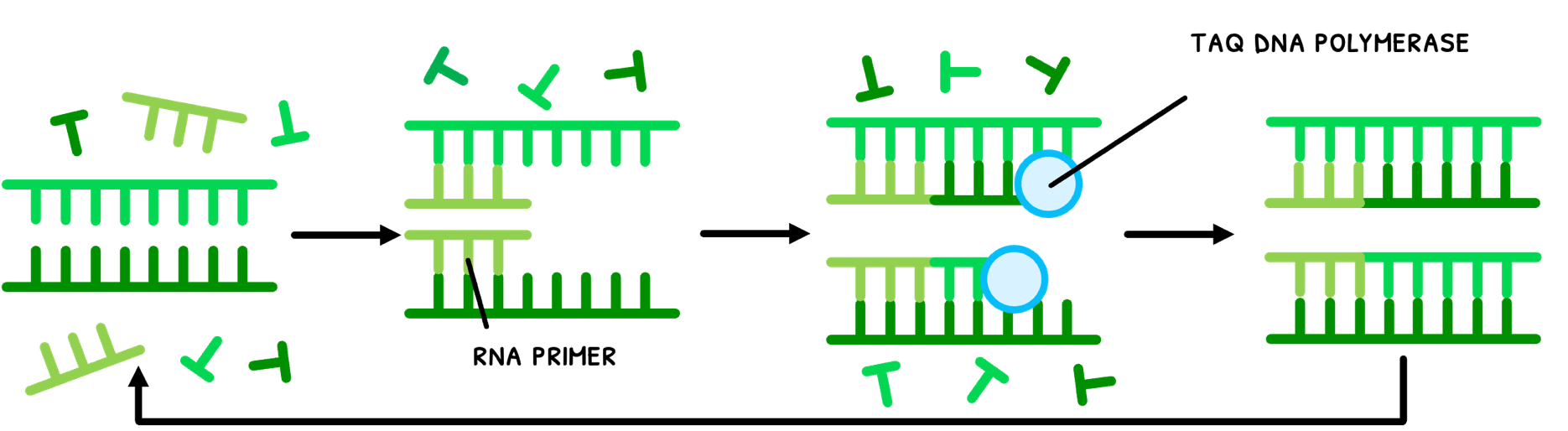

In this, samples of DNA are first collected from hair, semen, or blood. However, the amount of DNA present in these samples is insufficient to extensively test and have backups. Therefore, it first requires the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). This is a method of mass artificial DNA replication to generate substantial amounts of DNA for testing from a small sample such as hair or semen. The process is as follows:

- DNA mixed with primers is heated up to 95°C to split the strands.

- The temperature is lowered to 53°C to allow primers to bind (anneal).

- The temperature is increased to 73°C, the optimal temperature for Taq DNA polymerase to elongate the DNA.

- This process is repeated for a few hours to obtain millions of copies.

You are supposed to appreciate that at the high temperatures of the PCR process, normal human enzymes would denature. However, Taq DNA polymerase does not do this, because it stems from bacteria that live near volcanic vents deep in the ocean that are used to high temperatures. Therefore, the enzyme is not only naturally resistant to these high temperatures, but has its optimal activity there, allowing it to be constantly reused in this process.

Sail through the IB!

D1.1: Further DNA replication (HL)

DNA replication

In the HL syllabus, you need to understand the process of DNA replication in more detail. The process is as follows:

- DNA gyrase relieves kinks in the coiled DNA and unwinds the helix.

- DNA helicase then separates the DNA strands by breaking hydrogen bonds between the complementary base pairs.

- Single stranded binding proteins keep the strands apart.

- The existing strands are used as templates as DNA primase lays down RNA primer.

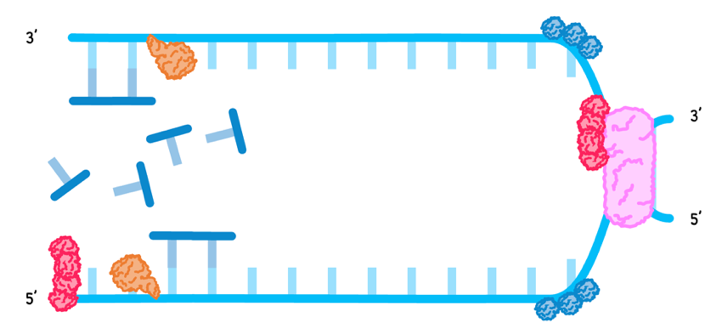

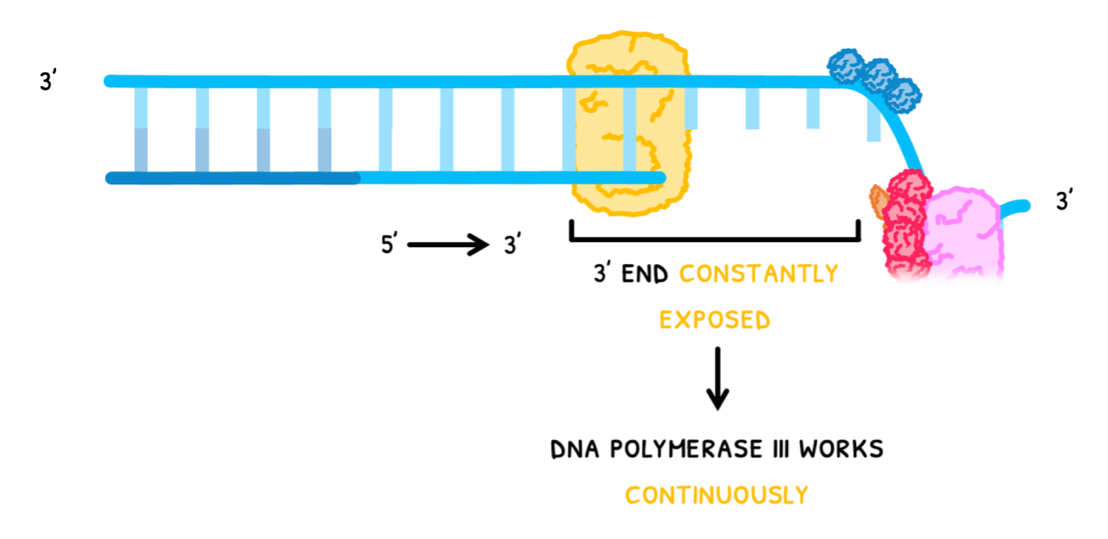

DNA polymerase III then binds to the RNA primer and links free nucleotides, known as nucleotide triphosphates, using complementary base pairing, in a 5’ to 3’ direction. This occurs differently on the strands:

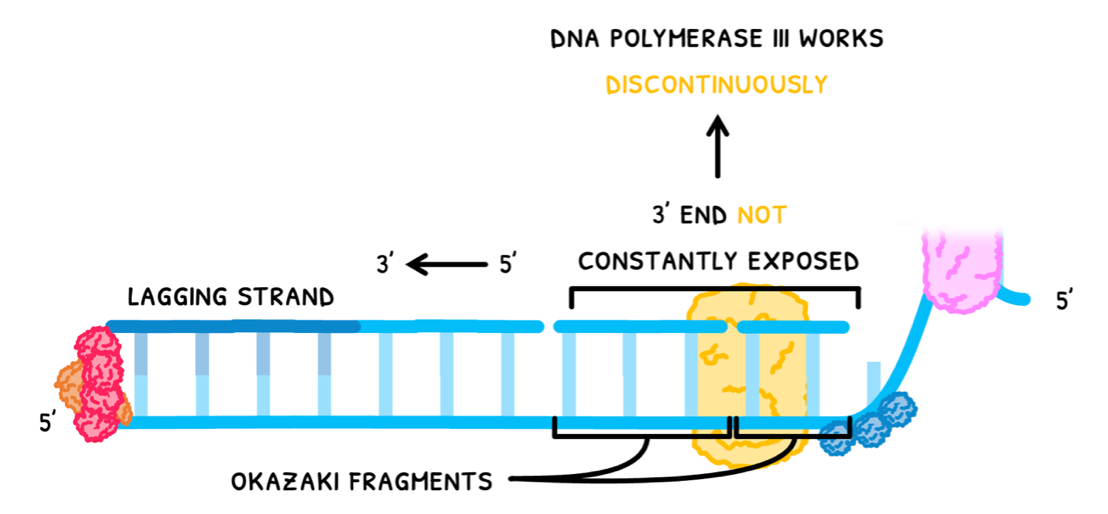

In one strand, the 3’ end is constantly exposed, so DNA polymerase III can work continuously. This is known as the leading strand, and it produces a single long strand of nitrogenous bases.

In the other strand, the 3’ end is not constantly exposed, so DNA polymerase III works backwards in short segments. This is known as the lagging strand, and it produces multiple short strands of nitrogenous bases, known as Okazaki fragments.

Sail through the IB!

D1.2: Protein synthesis

Transcription

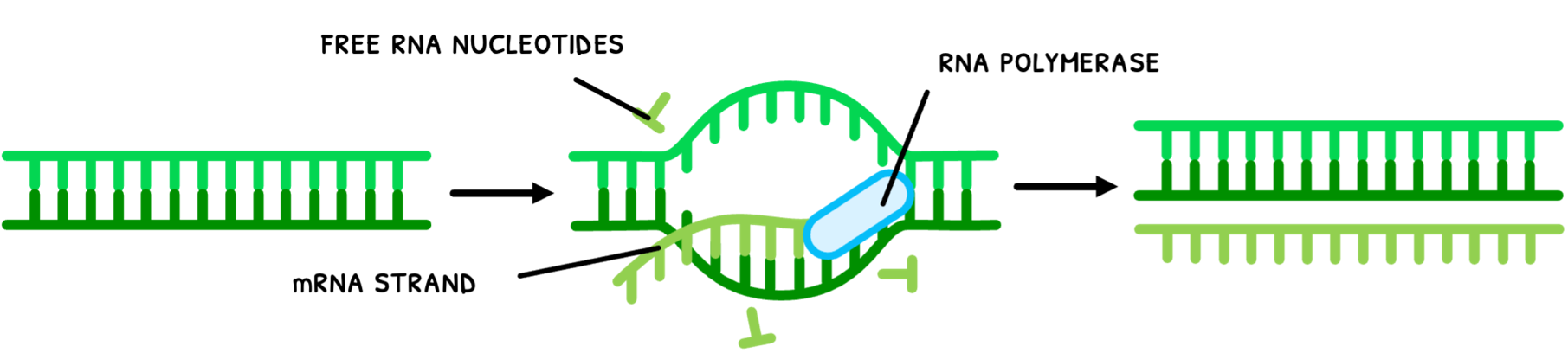

In Topic A1.2, you learned that nucleic acids code for protein production. Since DNA is located in the nucleus and proteins are produced outside the nucleus, the genetic code needs to be transported out of the nucleus. This done by messenger RNA (mRNA), which is produced by the process of transcription:

- RNA polymerase unwinds the double helix and separates the strands.

- RNA polymerase links nucleotides to one of the pre-existing strands via complementary base pairing (uracil instead of thymine with adenine).

- The mRNA strand separates from the DNA and the DNA pairs up again and twists back into a double helix.

Note that using single DNA strands fixed in the nucleus to nucleosomes as templates provides a very stable base from which to perform transcription. However, the base sequence cannot change so in cells that do not divide, these sequences cannot change throughout the entire life cycle of the cell.

Codons

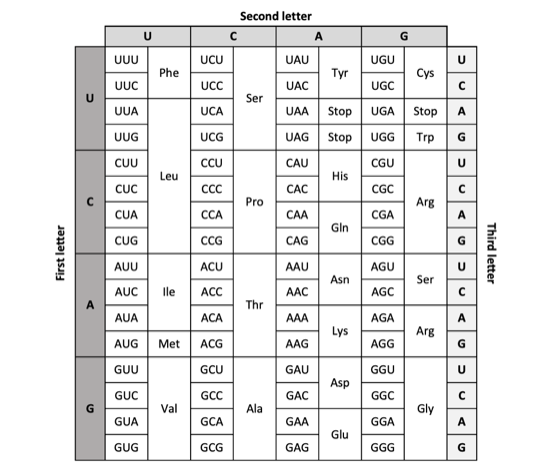

The generated mRNA then leaves the nucleus is used to produce proteins. In order to do this, there needs to be a conversion of RNA nucleotides to amino acids. The smallest possible combination of four nucleotides that can encode for all 20 amino acids is a triplet code. Four nucleotides and a doublet code could only yield 16 (42) amino acids and four nucleotides and quartet code (44) would code for 256 amino acids.

Thus, the mRNA strand is divided into nucleotide triplets, called codons. There are a total of 64 codon combinations (4 x 4 x 4), shown in the table below.

Each codon is associated with an amino acid, but there are only 20 amino acids for 64 codons. This means several codons will exist for the same amino acid, called the degeneracy of the genetic code. However, almost all organisms use the same codons for the same amino acids, called the universality of the genetic code.

Sail through the IB!

D1.2: Further protein synthesis (HL)

Non-coding sequences

HL students need to know more details about transcription and translation. Within the concept of gene expression, it is important to understand that the DNA sequences that are transcribed do not only result in proteins. There are several types of DNA sequences:

- Coding DNA - DNA that codes for proteins.

- Non-coding DNA - DNA that does not code for proteins. There are several types:

- Regulators - these promote or repress transcription of adjacent coding sequences.

- Introns - these are used during mRNA processing to aid the splicing of exons.

- Telomeres - the lagging strand loses a little bit of DNA every time it undergoes replication. Telomeres are extra lengths of DNA that prevent the loss of vital DNA.

- tRNA and rRNA production - these sequences are transcribed to form tRNA for translation and rRNA (ribosomal RNA) to form ribosomes.

In this topic, you will learn about about several of these non-coding sequences.

Initiation of transcription

This begins with sequences that regulate gene expression. This means that they regulate the initiation of transcription, which occurs differently in prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Since prokaryotes do not have nucleosomes to help with regulation, they directly regulate transcription. This is necessary to limit protein production via translation since all proteins are required at different concentrations and at different times, so it would be wasteful to constantly generate them.

In prokaryotes:

- Promotor sequences recruit RNA polymerase to the binding site to initiate transcription.

- However, repressor proteins can bind to DNA at the repressor binding region in response to environmental factors.

- This directly prevents RNA polymerase from performing transcription, thus decreasing the rate of transcription.

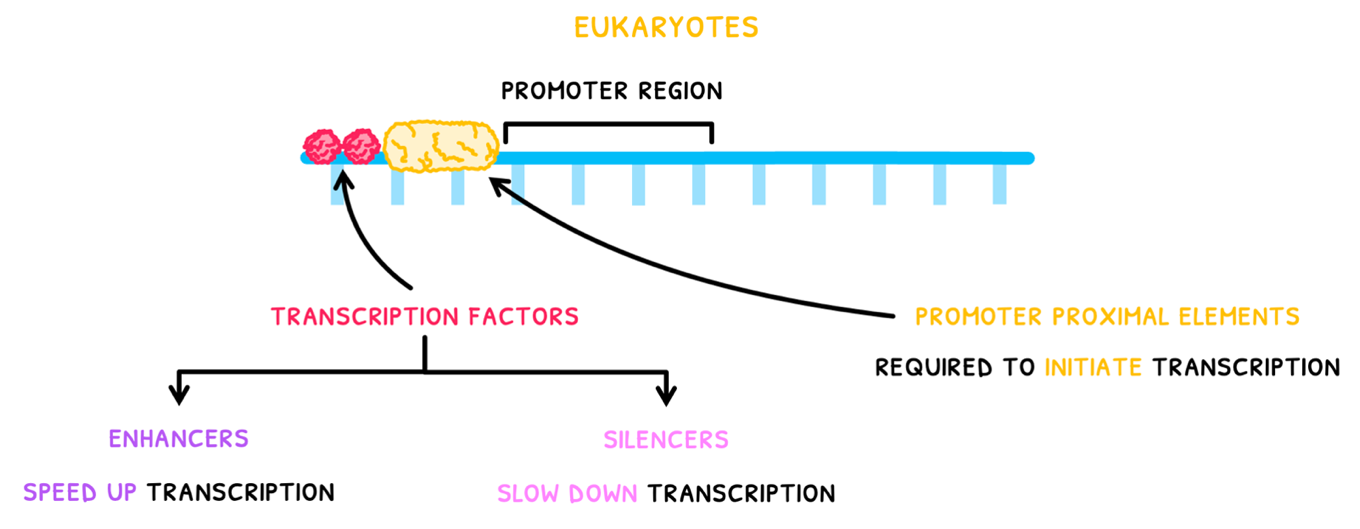

In eukaryotes:

- Promoter proximal elements are present near the promoter region to initiate transcription.

- Transcription factors bind to DNA before the promoter region.

- If these are enhancers, they initiate a cascade of promoter protein recruitment to the promoter region.

- Eventually, this recruits RNA polymerase to the DNA for transcription.

- If silencer factors bind to DNA, they slow down or prevent this process, slowing down transcription.

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

Sail through the IB!

D1.3: Mutations

Mutations

Just like the generation of new alleles, the process of evolution is often dependent on mutations. These are defined as changes in the base sequence of DNA. Most of the time they are not advantageous, but neutral, harmful, or lethal.

There are two main types of mutations you need to be aware of:

- A substitution mutation replaces one nucleotide with one another. Due to the degeneracy of the genetic code, this may produce a codon for the same amino acid, having no effect, or produce a codon for a different amino acid.

- A frameshift mutation refers to a mutation that shifts an entire part of the amino acid sequence by one or two nucleotides. This changes all the codons in that part, resulting in a different polypeptide.

- An insertion alters the DNA sequence by adding nucleotides to the gene.

- A deletion similarly will change the DNA sequence by removing nucleotides from the gene.

You can thus appreciate that mutations are more likely to cause harm than good. Since there is no cellular system in place to deliberately alter DNA sequences and change traits, mutations are mostly completely random.

However, some bases are more prone to mutation than others, meaning they are more likely to mutate. If this occurs, there are certain risks involved depending on the cell type involved:

- Germ cells - mutations in germ cells can be passed on to offspring and inherited, resulting in genetic diseases for children even if not present in the adult.

- Somatic cells - mutations in somatic cells can result in improperly functioning somatic cells, requiring medical treatment to compensate for. If the cell cycle is affected, then this can lead to cancer, which can be very treatable or terminal depending on the type.

Mutagens

Mutagens are radiation or chemicals that increase the rate of mutation. The three types you need to remember are:

- α, β, or γ radiation

- UV light

- Certain chemicals, such as the ones found in cigarettes.

Therefore, large scale releases of radiation increase cancer rates. You need to be aware of two examples:

- Hiroshima bombings killed 150,000-200,000 individuals in the blasts. However, survivors developed 17,448 tumours between them.

- Similarly, the nuclear meltdown of Chernobyl produced 6 tonnes of uranium particles, killing flora and fauna but more notably increasing the incidence of thyroid cancer markedly in survivors.

D1.3: Gene editing (HL)

Gene knockout

Now that you are aware of mutations and how to lead to genetic diseases and cancers, you can appreciate that considerable research has gone into medical genetics to solve these problems.

However, this first requires scientists to determine which genes perform which functions. This is done by gene knockout, which is a form of genetic engineering used to remove or inactivate one or more specific genes from an organism. Gene knockout can appear as two types:

- Complete - the gene is permanently deactivated.

- Conditional - the gene can be turned on and off by command.

The ability to perform gene knockouts is useful because a library of organisms with gene knockouts can be produced. These are then used as models in research to:

- Understand the impact of the gene on the organism's development and life.

- Discover the pathways of metabolic processes and the proteins involved.

- Develop treatments for genetic conditions that are otherwise untreatable.

You are expected to understand that gene knockout is typically performed via one of three methods:

- Homologous recombination - forced crossing over with an inactivated gene during meiosis, introducing that gene to the organism's genome.

- TALENs - nucleases that binds to a DNA domain and cleaves it to introduce a frameshift mutation and inactivate the gene.

- CRISPR-Cas9 - the Cas9 enzyme cleaves DNA to introduce various mutations for gene inactivation.

CRISPR-Cas9

Whilst you are not expected to know details of the first two methods, you need to know more about CRISPR-Cas9. It performs DNA insertion, deletion, or alteration to edit genomes via deliberate mutations. To accomplish this, two molecules are used:

- A guide RNA (gRNA) targets a specific DNA sequence in a gene and delivers Cas9.

- Cas9 cleaves the two DNA strands at the desired spot or location to add or remove DNA.

- It then allows the cell to repair DNA by itself, introducing a mutation in the process.

CRISPR Cas9 offers hope in the development of treatments for conditions that have a genetic component, such as certain cancers and hypercholesterolaemia and in certain viruses such as hepatitis B.

However, editing the genes of germline cells of humans raises questions of ethics. Changes made to such cells will be inherited by future generations, and can be potentially dangerous. As a result, it is currently an illegal practice in most countries.